9.01 – Pragmatic Investigation

Presented by: Iain Wilkinson, Jo Preston, Alice O’Connor

Broadcast Date: 18th February 2020

Social Media

Jo: Tweetorial on frailty scales

Learning Outcomes

Knowledge

- To understand that diagnosis at all costs does not always lead to improved outcomes

Skills

- To recognise when investigations may not lead to an improved outcome for an individual

Attitudes

- To have the confidence to speak openly with patients about their goals to guide treatments and interventions.

CPD Log

Show Notes

Definition

Pragmatism is defined as:

Dealing with things sensibly and realistically, in a way that is based on practical rather than theoretical considerations

Oxford Dictionary accessed 19/1/20

Main Discussion

Pragmatic investigation is pretty much the hallmark of geriatric medicine – there are often interacting problems and treatments, complicated by ageing physiological systems, leading to a high level of clinical complexity. These competing and confounding factors require a degree of pragmatism, an understanding of the evidence base where it exists, and an ability to tolerate uncertainty, in order to manage, care for, and advocate for the most vulnerable and frail of adult patients.

Kumar and Clark 10th Edition, Chapter 15 – to be published 2020

Too Much Medicine – BMJ

The BMJ runs an initiative called “Too Much Medicine”, which you may have seen in the journals or online. It aims to highlight the threat to human health posed by overdiagnosis and the waste of resources on unnecessary investigation and treatment.

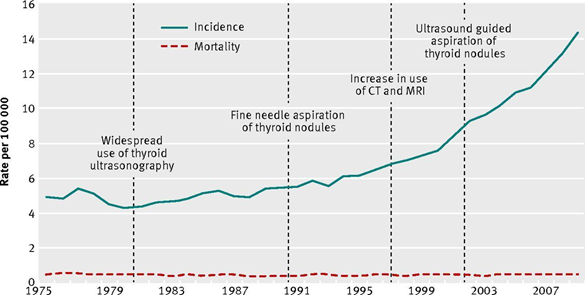

A nice visual example of overdiagnosis with no significant improvement in mortality comes from a BMJ article in 2013 on increased pick up rates of thyroid cancer.

These sorts of figures often make it into the mainstream news but without context (i.e. “soaring rates of thyroid cancer!”)

This may further drive health anxiety and over-investigation.

“Political drive to screen for pre-dementia: not evidence based and ignores the harms of diagnosis”

Note: this ties in nicely with a talk about low diagnostic rates of Alzheimer’s disease, summarised in this RCP conference report from 1996 (conference was entitled Medicine and Elderly People: over-investigation or under-treatment?)

Around 2012 the government called for dementia “screening” with the aim of having “A memory clinic in every town” to increase early diagnosis. However, there is limited evidence that memory clinics are more beneficial than routine care by a GP – worth noting that when they were introduced in the 1980s their main aim was to recruit patients to enter clinical trials of cholinesterase inhibitors. This drive was also questioned as dementia does not meet the WHO screening criteria (there is no strong evidence for any preventive or curative pharmacological intervention).

Couteur David G Le, Doust Jenny, Creasey Helen, Brayne Carol. Political drive to screen for pre-dementia: not evidence based and ignores the harms of diagnosis BMJ 2013; 347 :f5125

What is interesting here is those criteria for screening: no evidence for preventive or curative intervention. Geriatric Medicine often sits in between those two, and indeed medicine as a whole has also broadened from that definition to consider supportive care. A diagnosis of dementia allows supportive measures to be put in place, such as targeted input from mental health teams (similar to specialist nurse support in heart failure). We’ve previously discussed the benefits of early psychosocial intervention in dementia. An early diagnosis can also offer opportunities for advance care planning, advance directives, sorting out power of attorney etc.

In a system organised around single-organ disease, there are advantages to accessing specialist services; if not purely for interventions that may alter the course of a disease, then for the support they provide which may alter the experience of it and improve quality of life.

However, in our episodes on multimorbidity and polypharmacy we saw that being treated by multiple specialist teams for multiple conditions leads to harm. There is emerging evidence that strict adherence to “single organ” guidance for those with frailty can have detrimental effects.

For example:

- Maintaining tight glycaemic control/ low blood sugars in frail people with diabetes is more dangerous than accepting a looser HbA1c target.

- Blood pressure targets: no increased mortality with higher BP in those with frailty.

Treating Type 2 Diabetes in elderly people does more harm than good. Torjesen BMJ 2014

Is the association between blood pressure and mortality in older adults different with frailty? A systematic review and meta-anaylsis. Todd et al. Age and ageing 2019

To do nothing for the gomers was to do something, and the more conscientiously I did nothing the better they got.

The main source of illness in this world is the doctor’s own illness: his compulsion to try to cure and his fraudulent belief that he can.

The house of God – Samuel Shem

Common situations requiring pragmatism

A common scenario encountered with older adults is weight loss +/- iron deficiency anaemia:

- Established pathways exist for investigation of these, usually via 2 week wait.

- It can lead to fragmented care through multiple specialists or specialists focusing on one aspect or question.

- 2WW “cancer of unknown primary” clinics have pick up rate of around 10%, with significant alternative pathology found in a much higher percentage.

Questions often asked of geriatricians, explicitly or not, might be:

- Is the patient fit / suitable for the investigations?

- Are they fit / suitable for the treatments of potential diagnoses?

- Are there other conditions or factors that might be causing the symptom e.g. poor oral intake in dementia leading to nutritional deficiencies and low iron stores / weight loss.

These questions must be discussed with the patient in shared decision making. Finding the balance between these areas can prove difficult for patients and clinicians alike.

An example of this (that we have discussed previously in episode 6.02) is someone experiencing postural hypotension due to antihypertensives. We might accept a higher blood pressure to reduce the risk of the patient falling, or living in fear of falling.

It is worth remembering that older adults more frequently have “abnormal” results that do not signify disease, but rather the ageing process. For example:

Older subjects with unexplained anaemia had similar survival compared with non-anaemic subjects. Increased mortality risks were observed in subjects with explained anaemia compared with non-anaemic subjects

‘In 37% of anaemic subjects no clinical explanation for anaemia could be found, similar to earlier reports. Data from a non-institutionalised US population assessed in the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1988–94) showed that unexplained anaemia was present in one-third of the older adults (>65 years) with anaemia.

Between the three groups no differences in the cause of death were found.’

However: only looked at mortality, not morbidity/ symptoms etc.

No increased mortality risk in older persons with unexplained anaemia, Age and Ageing, Volume 41, Issue 4, July 2012

How to frame these decisions and their discussions:

Asking patients, in broad terms; How important is it for you to have a diagnosis for this, even if it can’t be cured? How comfortable are you without a clear answer? For some, having a diagnosis allows time for ACP and early referral to palliative care services, even if cure is not an option.

What would you be willing to go through to get a diagnosis? (i.e. How invasive?)

- CT scans: less sensitive, but may show large tumours. Interval scans can provide guidance over a longer period of time.

- Endoscopies: Most people can tolerate an OGD but colonoscopy more invasive, may not be able to manage the prep at home, or want to. May allow tissue diagnosis though.

- Biopsy: invasiveness depends on location of abnormality.

Running through from the other side: what treatments would be unacceptable to you if we found something?

- Surgery

- Chemotherapy

- Radiotherapy

As a clinician, asking yourself: would this person be fit for these things? We have a duty to offer viable treatment options, but not those which are not feasible (they are not options).

Another way to look at this is impact on prognosis or management…

Prognosis and management

One way to view these decisions is to consider how having additional information will alter management.

Example: 85 year old with chest infection on day 3 of IV antibiotics, who has admission chest x-ray showing left basal pneumonia, starts to spike temperatures again, drops sats, with mucous plugging and rising inflammatory markers. It is 3am – do you do a chest x-ray?

Example: 92 year old with asymptomatically abnormal LFTs and an ultrasound showing a dilated biliary tree. ERCP has failed twice for a combination of procedural difficulty and compliance, due to not recalling what it is for in context of cognitive impairment. Next step would be more invasive, higher risk procedure.

- Could be normal dilatation due to ageing

- Could be a stone

- Could be a tumour – either benign or malignant.

Having a diagnosis here of a pancreatic malignancy would alter prognosis significantly and could argue that this diagnosis would allow time for ACP, fast track support for care needs, for patient and family to spend time together. However, is that worth the increased risk of the investigation itself?

Will it alter management? This comes to an assessment of the odds of each diagnosis

- Stone or benign tumour may only require a stent: but if there are structural problems with the ERCP it is likely to be a higher risk intervention

- Normal ageing: nothing that will alter this

- Malignant tumour: fit for surgery / chemotherapy? What benefit would those provide?

If asymptomatic and not a candidate for available treatment options, then there is an argument to not investigate further. Alternative might be to monitor LFTs for signs of progression, this will

- Give relatively non-invasive information on progression and therefore narrow diagnosis and prognosis

- Allow intervention for symptom control and ACP at an earlier stage regardless.

Mnemonic for decision making: BRAN

B – what are the benefits of this investigation? Not missing a malignancy, having an accurate diagnosis that might guide care needs going forwards.

R – what are the risks of this investigation? Biliary tree perforation and bowel injury.

A – what are the alternatives to this investigation? No

N – what happens if we do nothing? May miss malignancy, but could monitor for signs of progression another way to ensure that the eligible treatment – in this case good early palliative care, can start early if required.

Curriculum Mapping

NHS Knowledge Skills Framework

- Core 1 Level 4

- Core 2 Level 1

- Core 5 Level 4

- HWB1 Level 1

- HWB6 Level 4

- HWB7 Level 4

Foundation Programme

- Sec 1:2 Patient centred care

- Sec 1:2 Consent

- Sec 1:4 Self directed learning

- Sec 2:6 Comm. patients/ relatives

- Sec 3:10 Frail pt

- Sec 3:10 Support for pts

- Sec 4:20 Healthcare resource management

GPVTS

- 3.05 Maintaining an ethical approach

- 3.05 Communication and consultation

- 3.05 Data gathering and interpretation

- Understand the changes in the normal range of laboratory values that are found in older people

- Know the special features of prognosis of diseases in old age and be able to apply the knowledge to produce an appropriate plan for further investigation and management, including end-of-life care

- Know that many cancers are more prevalent in the elderly population and may be insidious

- 3.05 Making decisions

- 3.05 Managing medical complexity

- Understand how co-morbidity will influence the management of existing disease and delay the early recognition of adverse clinical patterns

- 3.05 Practising holistically and promoting health

Core Medical Training

- Management and NHS structure: Resource allocation

- Other important Presentations:

- Incidental Findings

- Weight loss

- Geriatric Medicine

Internal Medicine Stage 1

- Generic CIPs – Category 1:1

- Complexity & uncertainty

- Generic CIPs – Category 2:3

- Communicate with patients

- Shared decision making

- Geriatric medicine

Geriatric Medicine Specialty Training

- Managing long term conditions and promoting patient self-care

- Quality of life

- Health promotion and public health

- Screening programmes

- Principles of medical ethics and confidentiality

- Ethical decision making

- Legal framework for practice

- 44. Care of Older People living with Frailty