7.04 Communication with relatives

Presented by: Dr Iain Wilkinson, Dr Jo Preston, Dr Carys Flemming and Chris O’Connor – Admiral Nurse

Broadcast date: 26th March 2019

Learning Objectives

Knowledge:

- To become familiar with some models for communication with relatives that may help to guide practice

- To be aware of common clinical situations where communication with relatives may be difficult

- To understand the legal and ethical principles relevant to communication with relatives

Skills:

- To be able to communicate with relatives effectively

- To be able to adapt the conversation depending on the needs and attitudes of the relatives

Attitudes:

- To understand some of the factors that may make communication with relatives challenging

Social Media this week…

Iain

@geriatricsdoc Time to rethink the word “fit”? What does it mean in #LaterYears? Certainly not that #Ageist version of 90 yr olds ‘still’ running marathons?https://t.co/rfLbilxSqP— grandmawilliams 80+ (@JoyceWilliams_) February 27, 2019

Jo

Carys

Involving family members in physiotherapy for older people transitioning from hospital to the community: a qualitative analysis https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5827976/

Main Show Notes

Definitions:

Practical Definition

Communication is key in forming and maintaining relationships between individuals in any walk of life. In particular, a therapeutic relationship between a health or social care worker and the person they are working with, requires open and clear communication in both directions. We need to be aware of the position of power afforded us in our roles often, and this often means that extra effort is required on our end.

Key Points from Discussion

In this episode we are going to concentrate mainly on the topic of communicating with relatives. Many of the principles will apply to talking to patients themselves. The reason for this focus is that we are assuming that communicating directly with a person about their condition or situation is second nature to many of us, and it is in those situations where they may not be able to speak for themselves that some of the most difficult situations can occur. Multiple opinions and agendas may come to the fore.

Legal and ethical principles

- As with everything in medicine, we are bound by law to meet certain requirements to protect our patients, and guided by certain ethical principles to act in their best interests.

- Two laws are key here

- Common law duty of confidentiality 1

- Mental Capacity Act 2005

- There are other laws relevant to patient confidentiality and disclosure of confidential information in specific situations, which GMC provides guidance on.

GMC ethical guidance for doctors

GMC guidance on disclosing personal information

Common law duty of confidentiality

- Before you disclose any information to a patient’s relatives, you need the patient’s consent.

- Best practise is to ask your patient for their consent before each disclosure. If there are things that they don’t want to be disclosed to relatives, then this must be respected.

- Often in practise we see HCPs assuming that patients consent for relatives to be included in discussion, for example where a patient attends A+E with a relative who remains present throughout the assessment, without the patient’s objection, and that’s okay, as per common law. This is implicit consent.

- However if there is any doubt, or where sensitive information is being discussed it is really important to have the patient’s consent before disclosing this to relatives. Failing to gain consent could compromise the patient’s trust in that HCP, or in all HCPs, and their subsequent interactions with the health service.

Mental Capacity Act

- When patients are unwell in hospital, it’s common for them to be unable to give consent, whether because they are unconscious or drowsy, delirious or have a long-standing cognitive impairment, or because they lack capacity for some other reason. That’s where the Mental Capacity Act becomes relevant. Remember that capacity is decision-specific, and that a patient should be assumed to have capacity until proven otherwise.

- If a patient can’t give their consent for an HCP to disclose information to their relatives, then as HCPs it is our responsibility to decide whether this would be in their best interests. If a relative has Power of Attorney for Health and Welfare, then legally we can disclose relevant information to that person to allow them to make decisions regarding the patient’s treatment. Remember you need to see it.

- Ethical dilemmas are not uncommon when deciding whether to disclose information to relatives. For example, when a patient has previous expressed that they do not wish for their relative to be informed of some clinical details of their case, and then they lose capacity and we wish to involve the relatives in decision making. Often there is not a clear right answer. What is important, as per the Mental Capacity Act, is that we act in the patient’s best interests and that we choose the least restrictive option. This may mean, for example, disclosing the minimum amount of information possible to the relatives to allow them to be involved in the decision making process, while respecting the patient’s previously expressed wishes to withhold certain information from them. It may mean asking for advocates to be involved or for second opinions from colleagues or ethics committees.

Common Clinical Situations where Communication with Relatives (and/or patients) can be difficult

In each of these scenarios you can see that the balance of power can feel unsettled and this may be what is making the exchange challenging.

- Where there is clinical uncertainty

- Upsetting or potentially upsetting topics

- Breaking bad news

- Deteriorating patients

- Where a patient’s care is transitioning from active to palliative

- Discussions about escalation and resuscitation, particularly where the relative’s opinions differ from those of the responsible clinician

- Where patient or relatives are angry, upset, or have a complaint

- Where a mistake has occurred which has caused harm or potential harm

- Where there has been a breakdown in communication between relatives and staff

- Where the relative’s opinions relating to discharge planning differ from the those of the MDT

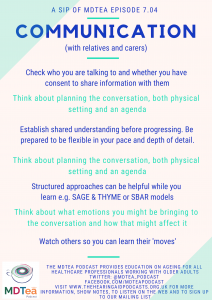

The SAGE & THYME model framework:

Setting: If you notice concern, think of the setting, create some privacy,

Ask: Can I ask what you are concerned about?

Gather: All concerns – not just the first few – ‘is there something else?’

Empathy: Respond sensitively – ‘you have a lot on your mind’.

Talk: Who do you have to help?

Help: How do they help?

You: What do you think would help?

Me: Is there something you would like me to do?

End: Summarize and close

SBAR works here also I think.

Practical Tips for Communicating with Relatives

- Establish who you are speaking to. Don’t make assumptions! Find out what the patient’s support network looks like. Are there other people who should be present for important discussions?

- Recognise and acknowledge their emotions. Fear can look like anger, and feeling like they’re not being involved in what’s happening to their sick relative can make people feel frightened. Relatives often feel like they are being kept in the dark, and it may be for as simple a reason as they haven’t known to ask for information. Lack of information can make people really frustrated or angry, and if you make it clear from the start that you are there to inform them and answer their questions, you can diffuse a tense situation very quickly.

- Miscommunications and mixed messages from multiple team members can be frustrating, and frightening. Apologise, and try to make sure everyone is on the same page.

- Do the relatives want to speak to you with the patient present, or without? (with patient’s consent)

- Setting. Assume the unconscious patient can hear you then ask if the relatives would prefer to stay or be elsewhere.

- Establish your agenda, and establish their agenda, at the start of the conversation. If there is a lot to discuss, or if time is short, it can help to set it out clearly, like stating the learning objectives at the start of a teaching session, or like a GP might do at the start of an appointment.

- Be flexible.. Sometimes you go into a conversation with an agenda and within a few seconds it becomes clear that you are on a completely different page from the person you are talking to. Be willing to be flexible, adapt or abandon your plan. It depends on how much time you have; if a patient is deteriorating quickly then sometimes you have to persevere to try and bring the family onto the same page as quickly as possible; if you have more time, you can take it, and remember that you’re building a relationship for the next days or weeks.

- Make sure they know that the decisions being made are not on their shoulders.

- Be aware of cultural differences (upcoming episode). Support networks are hugely diverse, and it’s important to approach every patient with an open mind and not to make assumptions before you have gathered information.

- Just because you’re comfortable talking about difficult topics, doesn’t mean that relatives are. Relatives get really anxious that patients will find some conversations distressing – sometimes correctly, and sometimes not. It may be helpful to ‘test the waters’ ahead of any conversations with family, with the person directly to establish a) how much they themselves wish to talk about and b) how much they want their family to know / be involved with. Establishing what they know already and what level of information they are comfortable with at the outset can be helpful e.g. are you the sort of person that likes all the details or the headlines? A gentle sentence like ‘I’m worried about how you are doing’, can open the conversation whilst allowing the person themselves control over the pace and content of the subsequent discussion. If relatives then express concern in a meeting, you will be able to talk about what that person wants or does not want to discuss. It also demonstrates that you are capable of having a non-traumatic conversation with the patient on a difficult topic.

- Acknowledge that the topic is difficult. Acknowledge their concerns. Point out that just because it’s an upsetting topic doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be discussed, and actually that it’s really, really important that it IS discussed.. Advocate for your patient, point out how it would feel to be kept in the dark e.g. to know something is wrong or that you’re dying but nobody is talking to you about it.

- A lot of communication skills with relatives are identical to those for patients –active listening, summarising back, open questions, ICE, ‘any other questions? Anything else you wanted to talk about?’. When will you next speak, and how can they contact you in the meantime? Don’t use jargon!

- Feedback important conversations to the rest of your MDT. In a perfect world everyone would read every word in the notes but in reality, people don’t always read the notes and context is often lost. The best way to prevent relatives getting mixed messages is to make sure the MDT is all on the same page.

Particularly Challenging Scenarios

DNACPR and treatment escalation decisions

These can be challenging because of the uneasiness of the situation on both sides. We talked earlier about situations in which patients and relatives can feel uncertain or ‘at sea’ and this can impact on the types of conversations that you will have, including how emotional they become. The same will happen to you and this is why more senior colleagues can have, what seems like the exact same conversation but it go better. It can help to feel best prepared on your side for these conversations. Also, take a moment to reflect before you start: are you tired, stress, hungry? You may not be able to do anything about these at that particular time, but an awareness will help you to recognise whether you need to take a minute to prepare and ‘wind down’. It can also be helpful if you feel yourself getting frustrated in a conversation, to know whether it is partly how you are feeling to begin with. Note episode on psychodynamic approaches to ageing ep 5.01.

As well as the above, remember:

- Decisions of this sort are legally medical decisions. A person cannot insist on a futile treatment. An equivalent for therapists would be that a relative cannot insist on bed-based rehabilitation if they will not benefit from it.

- PoA means speaking with that person as though they are the person they are advocating for. This still does not give them the right to insist, as the person would not either.

- Next of kin, in the absence of PoA technically has no legal standing, although we would all agree that active involvement in decision making should be undertaken. No-one, including the person themselves, nor the PoA can insist on a futile treatment. A judgement call needs to be made on the impact on your therapeutic relationship for other aspects of treatment though, to push through a decision like this.

Joint decision making is likely to be the most successful. Using phrases that allow you find out as early as possible how close to common ground you are can be really helpful. You can then work out how to meet them there. Try things like:

- So your mother has been unwell for a few months now, tell me what has been happening – this often allows the person themselves to acknowledge any deterioration leading up to this point.

- You mentioned that your mum can’t walk very far – this can then lead to a discussion about physiological reserve in the face of an illness.

- Your mum is very unwell right now, have the two of you ever had any conversations about what she would or wouldn’t want to happen in situations like this?

- If your mum could hear us talking now, what do you think she would say about it? – this often alleviates the pressure felt by a loved one about how they feel vs what they think their relative would want.

Through the use of clinical vignettes, one study looked at how 3 different levels of shared decision making after a clinical error where interpreted by the American public. Those with brief, but thorough shared decision making, were 80% less likely to report a plan to contact a lawyer than those not exposed to shared decision making (12% and 11% versus 41%; odds ratio 0.2; 95% confidence interval 0.12 to 0.31). Participants exposed to either level of shared decision making reported higher trust, rated their physicians more highly, and were less likely to fault their physicians for the adverse outcome compared with those exposed to the no shared decision making vignette.

The effect of shared decision making on patient’s likelihood of filing a complaint or lawsuit: A simulation study. Schoenfeld et al. Annals of Emergency Medicine 2019.

References

- https://www.gmc-uk.org/ethical-guidance/ethical-guidance-for-doctors/confidentiality/disclosing-patients-personal-information-a-framework#paragraph-13

- 2) GMC. Confidentiality: key legislation https://www.gmc-uk.org/ethical-guidance/ethical-guidance-for-doctors/confidentiality/~/-/media/59240e8f25da48d4b56c6fd93069e5d8.ashx

Curriculum Mapping

This episode covers the following areas (n.b not all areas are covered in detail in this single episode):

- NHS Knowledge Skills Framework

- Core Dimension 1: Communicaiton – Levels 1-4

- HWB4: Enablement to address health and wellbeing needs.

- Foundation curriculum (2016)

- 6. Communicates clearly in a variety of settings – Communication with patients/relatives/carers

- Core Medical Training

- History taking

- Relationships with patients and communication within a consultation

- Complaints and medical error

- GPVTS program

- 2.01 The GP Consultation in Practice – Core Competence: Communication and consultation

- 3.05 Care of Older Adults – Core Competence: Communication and consultation

- Geriatric Medicine Training Curriculum

- 3.1 Principal Learning Objectives

- 1. History Taking

- 12. Relationships with Patients and Communication within a Consultation

- 14. Complaints and Medical Error