6.03 Hypertension

Hypertension

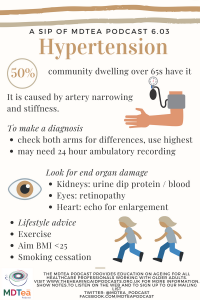

In this episode we look at the diagnosis and issues surrounding the diagnosis of hypertension.

Presented by: Dr Jo Preston, Dr Iain Wilkinson and Dr Mike Okorie

Faculty: Pam Trangmar PA

Join the discussion with #mdteaclub on twitter

Social media this week

Iain

When someone describes ‘good bedside manner’ they usually are referring to regular manners.

— Millennial med (@Millennial__MD) August 14, 2018

Jo

So excited to see this released! Nice work @clshenvi @drmikegerardi @MauraKennedyMD! @CPE_PsychEmerg @TheEMFoundation #agitation pic.twitter.com/hkIdWZGAIZ

— LorenRives (@LorenRives) August 9, 2018

The Gallery

‘Just one word’ – Poem by Alison Bolus

Learning outcomes

Knowledge:

To understand the importance of hypertension control for some patients

To have a greater insight into the research basis of hypertension control in older people

Skills:

To be able to explain to a patient the non-pharmacological interventions to control blood pressure

To be able to explain the pros and cons of anti-hypertensive treatment to an older person and their family

Attitudes:

To understand that prescription of anti-hypertensives is an individualised process and there is no one size fits all.

Show Notes

Pdf of show notes is here.

Definitions:

In this guideline the following definitions are used.

- Stage 1 hypertension Clinic blood pressure is 140/90 mmHg or higher and subsequent ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) daytime average or home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM) average blood pressure is 135/85 mmHg or higher.

- Stage 2 hypertension Clinic blood pressure is 160/100 mmHg or higher and subsequent ABPM daytime average or HBPM average blood pressure is 150/95 mmHg or higher.

- Severe hypertension Clinic systolic blood pressure is 180 mmHg or higher or clinic diastolic blood pressure is 110 mmHg or higher

NICE Clinical Guidelines Hypertension (CG127)

Practical Definition

Hypertension in the office is defined as systolic BP ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic BP ≥90 mmHg. The cut-off value for home BP (or daytime ambulatory BP) is 135/85 mmHg.

European society of cardiology – Hypertension guidelines

QUESTIONS FROM ESC GUIDELINE:

Should elderly patients with a SBP between 140 and 160 mmHg be given antihypertensive drug treatments?

Arelifestyle measures known to reduce BP capable of reducing morbidity and mortality in hypertensive patients?

Key Points from Discussion

Why does HTN happen in older people?

The structure and function of the vascular tree changes with advancing age. Arteries narrow as a result of atherosclerosis, but also stiffen, leading to differences in how the systolic pressure wave is propagated through the arterial tree. The loss of diastolic augmentation caused by stiff major arteries leads to a fall in perfusion pressure in the coronary arteries, and changes in cerebrovascular circulation lead to reductions in cerebral perfusion reserve.

Simon Conroy, Rudi Westendorp, Miles Witham. Hypertension treatment for older

people— navigating between Scylla and Charybdis. Age and Ageing 2018; 47: 505–508

- The major effects of normal aging on the cardiovascular system involve alterations of the aorta and of the systemic vasculature. Aortic and large-artery wall thickness increases and vessel elasticity decreases with age. These changes induce a decline in aortic and large-artery compliance and an elevation of SBP.

- The reduction of vessel elasticity results in an increase in peripheral vascular resistance.

- Baroreceptor sensitivity is modified with age. Alterations in baroreceptor reflex mechanisms may explain the variability of BP revealed by continuous monitoring.

- Decreased baroreceptor sensitivity results in an impairment of postural reflexes, making elderly hypertensive individuals more sensitive to orthostatic hypotension. [link to postural hypotension 6.02]

- Changes in the balance between β-adrenergic vasodilation and α-adrenergic vasoconstriction are in favor of vasoconstriction that increases peripheral vascular resistance and BP.

- Sodium retention due to increased intake and decreased excretion could also contribute to hypertension. A fall in plasma renin with increasing age has been demonstrated.

- The renin response to salt intake is more reduced with age in hypertensive than in normotensive elderly subjects; however, the renin-angiotensin system is not regarded as playing a major role.

- These changes are responsible for decreased cardiac output, decreased heart rate, decreased myocardial contractility, left ventricular hypertrophy, and diastolic dysfunction. They induce an impairment of renal function with decreased renal perfusion and reduced glomerular filtration rate

We talked about the problems of a low BP earlier in the series and there is a U shaped curve for mortality so we need to think about a balance.

We know from long term studies (such as Framingham) that HTN is not good for you and is associated with negative health outcomes. Framingham study is the origin of the term Risk Factor. It showed that healthy diet, not being overweight or obese, and regular exercise are all important in maintaining good health.

Framingham led to the development of a 10 year cardiovascular risk calculator

But first we need to know how to measure BP accurately

How to measure blood pressure:

- When considering a diagnosis of hypertension, measure blood pressure in both arms.

- If the difference in readings between arms is more than 20 mmHg, repeat the measurements.

- If the difference in readings between arms remains more than 20 mmHg on the second measurement, measure subsequent blood pressures in the arm with the higher reading. [2011]

- If blood pressure measured in the clinic is 140/90 mmHg or higher:

- Take a second measurement during the consultation.

- If the second measurement is substantially different from the first, take a third measurement.

- Record the lower of the last two measurements as the clinic blood pressure. [2011]

- If the clinic blood pressure is 140/90 mmHg or higher, offer ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) to confirm the diagnosis of hypertension. [2011]

NICE Clinical Guidelines Hypertension (CG127)

- If the person has severe hypertension, consider starting antihypertensive drug treatment immediately, without waiting for the results of ABPM or HBPM

- Refer the person to specialist care the same day if they have:

- accelerated hypertension, that is, blood pressure usually higher than 180/110 mmHg with signs of papilloedema and/or retinal haemorrhage or

- suspected phaeochromocytoma (labile or postural hypotension, headache, palpitations, pallor and diaphoresis).

- While waiting for confirmation of a diagnosis of hypertension, carry out investigations for target organ damage (such as left ventricular hypertrophy, chronic kidney disease and hypertensive retinopathy) (see recommendation 1.3.3) and a formal assessment of cardiovascular risk using a cardiovascular risk assessment tool (see recommendation 1.3.2). [2011]

NICE Clinical Guidelines Hypertension (CG127)

Lifestyle interventions

Appropriate lifestyle changes are the cornerstone for the prevention of hypertension and are also important for its treatment.

- lifestyle advice should be offered initially and then periodically to people undergoing assessment or treatment for hypertension. [2004]

- Relaxation therapies can reduce blood pressure and people may wish to pursue these as part of their treatment. However, routine provision by primary care teams is not currently recommended. [2004]

- Discourage excessive consumption of coffee and other caffeine-rich products. [2004]

- A common aspect of studies for motivating lifestyle change is the use of group working. Inform people about local initiatives by, for example, healthcare teams or patient organisations that provide support and promote healthy lifestyle change. [2004]

- Salt restriction to 5-6 g/day.

- Moderation of alcohol consumption (<20-30 g of ethanol per day in men and <10-20 g in women).

- Increased consumption of vegetables, fruits and low-fat dairy products.

- Reduction of weight to BMI of 25 kg/m2 .

- WeRegular exercise (≥30 min of moderate dynamic exercise on 5-7 days per week)

- Smoking cessation

NICE Clinical Guidelines Hypertension (CG127)

European society of cardiology – Hypertension guidelines

Some key studies

A meta-analysis of 15 trials of people aged ≥60 (n = 24,055) showed that treatment was associated with a relative risk (RR) for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality of 0.72 (95% CI: 0.68, 0.77) and RR for total mortality of 0.90 (95% CI: 0.84, 0.97)

HYVET STUDY

RCT: 3845 patients from Europe, China, Australasia, and Tunisia who were 80 years of age or older and had a sustained systolic blood pressure of 160 mm Hg or more to receive either the diuretic indapamide (sustained release, 1.5 mg) or matching placebo. The angiotensin-converting–enzyme inhibitor perindopril (2 or 4 mg), or matching placebo, was added if necessary to achieve the target blood pressure of 150/80 mm Hg. The primary end point was fatal or nonfatal stroke.

Mean BP reduction was 15/6.

Active treatment was associated with a 30% reduction in the rate of fatal or nonfatal stroke, a 39% reduction in the rate of death from stroke, a 21% reduction in the rate of death from any cause, a 23% reduction in the rate of death from cardiovascular cause, and a 64% reduction in the rate of heart failure.

Participants in the Hypertension in the Very Elderly trial (HYVET) were all aged over 80, but had lower mortality than would be expected for this age group; they had much lower levels of diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

In HYVET, increasing frailty was associated with bigger treatment effects from BP lowering;

SPRINT TRIAL

- SPRINT included 9,361 adults age 50 or older who had systolic pressures of 130 mm Hg or higher and at least one other cardiovascular disease risk factor.

- Approximately 28 percent of the SPRINT population was age 75 or older and 28 percent had chronic kidney disease (CKD).

- In adults age 50 and older who had high blood pressure and at least one additional cardiovascular disease risk factor, but who had no history of diabetes or stroke, SPRINT showed that treating to a target systolic blood pressure of less than 120 mm Hg reduced rates of high blood pressure complications, such as heart attack, heart failure, and stroke, by 25 percent. Compared with the standard target systolic pressure of 140 mm Hg, treating to less than 120 mm Hg also lowered the risk of death by 27 percent.

- SPRINT included a large group of adults age 75 and older, and a separate analysis confirmed that treating to a lower blood pressure target reduced complications of high blood pressure and saved lives in older adults, as with the overall study population, even for older study participants who had poorer overall health. This was an important finding because a large percentage of the U.S. population age 75 and older have high blood pressure.

- Similar to the larger group, SPRINT showed that treating to the lower target goal of less than 120 mm Hg reduced high blood pressure complications for these participants. SPRINT found no difference in the main kidney outcomes—onset of end-stage renal disease or a 50 percent decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR)—between patients in the higher or lower blood pressure treatment groups.

Frailty status or gait speed had no association with treatment effect size in SPRINT.

COCHRANE REVIEW:

We found and included three unblinded randomised trials in 8221 older adults (mean age 74.8 years), in which higher BP targets of less than 150/90 mmHg (two trials) and less than 160/90 mmHg (one trial) were compared to a lower target of less than 140/90 mmHg.

Treatment to the two different BP targets over two to four years failed to produce a difference in any of our primary outcomes, including all-cause mortality (RR 1.24 95% CI 0.99 to 1.54), stroke (RR 1.25 95% CI 0.94 to 1.67) and total cardiovascular serious adverse events (RR 1.19 95% CI 0.98 to 1.45). However, the 95% confidence intervals of these outcomes suggest the lower BP target is probably not worse, and might offer a clinically important benefit.

We judged all comparisons to be based on low-quality evidence.Data on adverse effects were not available from all trials and not different, including total serious adverse events, total minor adverse events, and withdrawals due to adverse effects.

But… some suggestion here that a target of 150/90 was ok…

PARTAGE study

A total of 1,126 subjects (874 women) who were living in French and Italian nursing homes were enrolled (mean age, 88 5 years).

Central (carotid) to peripheral (brachial) pulse pressure amplification (PPA) was calculated with the help of an arterial tonometer.

2-year follow-up,

Results:

A 10% increase in PPA was associated with a 24% (p 0.0003) decrease in total mortality and a 17% (p 0.01) decrease in major CV events.

Systolic BP, diastolic BP, or pulse pressure were either not associated or inversely correlated with total mortality and major CV events.

Conclusion:

Low PPA from central to peripheral arteries strongly predicts mortality and adverse effects. High BP is not associated with higher risk of mortality or major CV events in this population…

Benetos et al. Mortality and cardiovascular events are best predicted by low central/peripheral pulse pressure amplification but not by high blood pressure levels in elderly nursing home subjects: the PARTAGE (Predictive Values of Blood Pressure and Arterial Stiffness in Institutionalized Very Aged Population) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012 Oct 16;60(16):1503-11.

Shared Decision Making

Link to ACP episode [6.01] in which we talked about studies demonstrating safety in depresribing antihypertensives.

Overall, 125 patients with a systolic BP of 170 mmHg have to be treated for 5 years to prevent one death.

Fewer (67) need to be treated to prevent a stroke and

fewer still (48) to prevent heart failure.

Curriculum mapping

| Curriculum | Area |

| NHS Knowledge Skills Framework | Suitable to support staff at the following levels:

|

| Foundation curriculum | 2. Delivers patient centred care and maintains trust

– Patient Centred Care – Trust 10. Recognises, assesses and manages patients with long term conditions

13. Prescribes Safely

16. Demonstrates understanding of the principles of health promotion and illness prevention |

| Core Medical Training | Therapeutics and safe prescribing

Managing long term conditions and promoting patient self-care Evidence and guidelines Cardiology – Section on Hypertension Mx |

| GPVTS program | Section 2.03 The GP in the Wider Professional Environment

Section 3.05 – Managing older adults

|

| ANP (Draws from KSF) | 7.15 Hypertension |

| Higher Specialist Training – Geriatric Medicine | 3.2.3 Presentations of Other Illnesses in Older Persons

29. Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Disease and Disability 45. Stroke Care |

| PA Matrix of conditions | Cardiovascular – Hypertension |