5.01 – Psychodynamic Approaches to Care for Older Adults

Episode 5.01 Psychodynamic Approaches to Care for Older Adults

Presented by: Dr Cate Bailey & Dr Juliette Brown (Old Age and Adult Psychiatry Specialist Registrars) and Dr Jo Preston & Dr Iain Wilkinson

Faculty: Bethan Moseley, Liaison Psychiatry for Older Adults, Jackie Lelkes, Social Worker, Gabor Szekely, GP.

Broadcast Date: 6th February 2018

Social Media Links discussed in episode:

Iain’s Pick

The “cascade of dependency” , depicts the hospital stay of a lady with dementia. All route cause analysis be presented like this! #Geriatrics pic.twitter.com/qOORSCf60T

— Dan Thomas (@dan26wales) January 15, 2018

Jo’s pick

Paper from @CCACE: Withdrawal of antihypertensive therapy in people with dementia: feasibility study. https://t.co/g8DL0HOcbf

— Andy MacLeod (@nailest) January 18, 2018

CPD log

Click here to log your CPD online and receive a copy by email.

Show Notes (download here)

Learning Outcomes

Knowledge:

- To develop a basic understanding of core concepts in psychodynamic theory relevant to the care of older adults

- To appreciate how a psychodynamic perspective can help in making sense of complex, bewildering and frustrating clinical encounters.

Skills:

- To be able to identify when a psychodynamic perspective might be most helpful

- To think about the personal meaning of challenges faced in the ageing process.

- To develop skills to observe clues to unconscious communication

Attitudes:

- Openness to thinking about the inner and outer worlds of ourselves and our patients

- To foster containment and thoughtful care

Definitions:

What is psychodynamic theory and why might it be useful in thinking about older adults?

Essentially psychoanalytic theory, or psychodynamic theory is premised upon the following:

- There is an unconscious part of the mind that influences action, thought and feeling

- Models of relationships throughout life are based on early important attachments (including capacity to trust and depend)

- Human development is rooted in childhood experience both real and imagined, which shapes responses throughout life but can be adapted by thought at later ages

- The mind operates defences to protect us from conflict and anxiety (often unconscious) and from being overwhelmed by painful realities

- Conflict is often the result of a difference between how things are and how we would like them to be.

Psychodynamic factors are always present, affecting to a greater or lesser extent such things as presentation of symptoms of illness, response to treatment and staff-patient interactions (Evans & Garner, 2004).

http://apt.rcpsych.org/content/aptrcpsych/8/2/128.full.pdf (Garner Article)

Caveats:

- We are psychiatrists, but we are not just talking today about people with diagnosed mental illness. Rather we are considering a wider set of patients who may have emotional difficulties adjusting to illness or loss and will be thinking about stresses produced by ageing.

- We are not describing psychotherapy with older adults although psychotherapy does take place and is a recommended and effective treatment, particularly for depression and anxiety (NHS Scotland, 2011)

- We are talking about using theories rooted in a century of psychoanalytic thought to better understand the distress of patients and our response to it

- These concepts aren’t new, and we’ve been lucky to observe supervisors who have used them effectively in a range of clinical settings. We appreciate that this may not be the case for all clinicians and so some of the ways of thinking may feel new and uncomfortable.

Many schools of thought in psychology from behavioural and cognitive (eg: CBT), to more dynamic. Both psychologists and psychiatrist may have knowledge of these theories and use them, but we also feel they could be applied to NHS practice outside of psychiatry and psychology – to understand better the emotional effects of illness and caring for others.

Practical Definition

...or why are psychodynamic theories, a theory of unconscious processes, relevant to caring for older adults?

- Old age and illness are sources of stress and they may trigger particular defences and responses.

- The mind is in dynamic relationship with earlier life experience. Patterns of relating in early life are likely to persist.

- Being a patient in itself evokes feelings relating to previous experiences of care (particularly infancy).

Being unwell can then result in people behaving in ways that appear maladaptive, that can confound our understanding as health care professionals, but the insights of psychodynamic theory can help. We’ll talk about a case shortly which will illustrate some of these concepts, and demonstrate how you might use them to make sense of clinical situations that are difficult. Allowing time to think in this way about the dynamics can potentially save time later, pre-empt further difficulties and enable better care.

Key Points from Discussion

Where did these ideas come from?

In 1895 Freud (neurologist) and Breuer (physician) published “Studies on Hysteria” in which they suggested that every hysteria (anxieties and medically unexplained symptoms) is the result of a traumatic experience which cannot be integrated into the person’s understanding of the world. This went onto be the basis for the idea of “conversion” (unconscious conflict is converted into physical symptoms). Freud went onto develop techniques for accessing the unconscious mind, including hypnosis and later free association, which lead to psychoanalytic techniques.

Post-Freudians who have applied psychoanalytic theory to older adults include Hanna Segal, Pearl King, Peter Hildebrand, Brian Martindale and Margot Waddell.

Defence mechanisms

We are going to talk a little about defence mechanisms. The word defence tends to have negative connotations, but defence mechanisms are thought to serve a protective function. Freud observed repression of mental conflict as a primary defence. His daughter Anna Freud went on to describe other defences.

Theorists have categorised them as more or less effective, over the long term, as coping strategies. We all depend on defences to function.

| Defense Mechanism | Description | Example |

| Repression | Unacceptable or unpleasant feelings are placed outside of consciousness. | Not remembering details of a traumatic incident (eg: receiving a diagnosis of a terminal illness) |

| Regression | Reverting back to an earlier stage of emotional development. | Requiring more support with ADLs in hospital despite being physically and cognitively able. |

| Displacement | Redirecting unacceptable feelings from the original source to a safer, substitute target. | Children taking anger out on hospital staff, rather than on their mother for whom they feel ambivalent or conflicted emotions. |

| Sublimation | Redirection of unacceptable impulses or desires into socially acceptable behaviour | Channelling frustration at having cared for a sick relative into becoming heavily involved in a charity for that condition. |

| Reaction formation | Acting in exactly the opposite way of one’s unacceptable impulses | A daughter taking perfect care of her abusive and neglectful mother in her later years. |

| Projection | Attributing one’s own feelings and thoughts to others | A patient accusing staff of being disgusted by having to care for him. |

| Omnipotence | Dealing with anxiety or conflict by acting as if one has no need of others | Patient claims they can manage without care package, despite assessments on ward suggesting they need help. |

| Rationalisation | Creating false excuses for one’s unacceptable feelings, thoughts or behavior. | Justifying benefits fraud on the grounds that the existing benefits are insufficient. |

| Splitting | Failure to integrate positive and negative qualities or elements of a situation or person. | Results in experiencing one person as all good and another as all bad within a team. |

(Adapted from (Milton, Polmear, & Fabricius, 2011))

We can begin to see how being aware of and able to observe some of these defences can be extremely useful in a clinical context. They can be a key to appreciating that things are not always what they seem.

Developmental theories

The child is the father of the man – William Wordsworth (1802)

We spoke about psychoanalytic theory as a theory of human development.

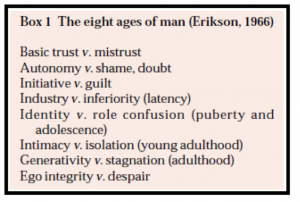

One particularly useful developmental model is that of Erikson, who describes the core task of later life as a negotiation between integrity and despair.

Psychological challenges of ageing

Psychodynamic theorists have identified a number of challenges associated with ageing:

- Loss or change in aspects important to self and identity – work, place of residence, relationships, friendships, intimacy and sexuality, appearance, the esteem and respect of society, visibility, physicality, functional and intellectual abilities. Self-reliance.

- Another caveat here of course is that there are many positives to ageing

- Many older people navigate these with little disturbance, but for others these losses may be more difficult.

- The extent to which these losses or changes spur, threaten or arrest emotional growth depends on how securely the adult state of mind was established earlier and the success or failure of previous struggles with separation and loss (Waddell, 2002).

Aging can be viewed as a narcissistic wound. On a spectrum from healthy to unhealthy narcissism - healthy narcissism will include self-respect and pride. It is functionally important to have a sense of one’s competence and independence in adult life. But narcissism can also be a defence – a way of retreating from dependency, envy, separation and loss and creates a state of apparent self-reliance often with a superior or self-aggrandizing quality. People who have written about this include Kohut, Kernberg and Winnicott (For further reading see chapters in (Evans & Garner, 2004)).

The narcissistic defence may be challenged for the first time in older age, where the reliance and identification upon the external world, and the body, the physical or mental abilities are no longer able to be maintained, no longer brings reassurance or praise. We often assume that people who become depressed after retirement simply do so because of boredom, but there can be more to the story, ie: rather than just the loss of the commitment and distraction of work, but also of the status, identity, achievements of adulthood that maintain a narcissistic defense. This is of course compounded by our society valuing youth, beauty and achievement, and devaluing older people, dependence, and indeed caring professions such as care home work.

Aging also means needing to come to terms with what has and hasn’t been achieved, adapt to the reality of the life which has been lived. There can also be anticipatory losses, such as in dementia. With a new diagnosis like dementia one may lose the version of old age that one had expected, and have to face disappointing others’ expectations also, with an effect on relationships with others.(There is a growing body of literature on dementia, which we won’t touch upon today, see (Evans & Garner, 2004) and (Davenhill, 2007).

Of course what else looms large in older age is the imminent prospect of death. Metaphorically and literally the prospect of death is the ultimate test of all efforts to come to terms with loss and to experience the reality of suffering (as well as the pleasures of life) – to suffer rather than to evade it by defensive measures.

For many people the prospect of dependency is more frightening than death. Old age often means having to rely on others for basic survival needs – feeding, washing, dressing, toileting. Each of these challenges may be associated with a process of mourning – feelings of bewilderment, disbelief, and rage - at the state of affairs.

How an individual responds to these challenges is a complex interaction of early life experience, patterns of interaction, defences, and external factors.

For those who are interested in further reading on early life attachments, and the importance of the early life environment, might want to read Bowlby, Winnicott, Bion.

These ideas are referenced in Evans, S and Garner J in relation to older adults (Evans & Garner, 2004)

Questions to ask to begin to reflect on a situation or interaction (think about with the following case):

- How does it feel to be with this patient? And what might this tell me about their experience?

- What is not being said? And how are past patterns of behaviour or relating being repeated?

- How might this person’s early life shape their experience of caring or being cared for?

- How might thinking about these things help me to better care for them?

Case

Henry is a 70 year old man who is on the surgical ward following a planned bowel resection for (potentially curable) colon cancer which required colostomy. He is referred to geriatricians as the junior surgical doctors think that he may be delirious, or have dementia, as he is unable to learn how to manage his stoma. He seems withdrawn at times, sometimes hostile and almost paranoid. His discharge is delayed and the surgeons feel the geriatricians should take over his care. He lives alone, is independent with all his ADLs, and is an active volunteer for the Alzheimer’s Society. He lost his wife to dementia 3 years ago, and had cared for her at home until her death.

The geriatrician who sees him feels his refusal to learn how to use the colostomy bags indicates depression rather than delirium. He makes a poor effort on cognitive testing but seems to be quite aware of recent events. He claims he was unaware of the possibility of stoma and would have refused the surgery had he known. He asks the geriatrician if she can help him end his life.

(Not remembering the surgery information could be repression. Appearing to be unable to learn to use the colostomy, despite being cognitively and physically able could represent repression. *It is important to note that some regression is normal in hospital – due to loss of agency (personal autonomy and effectiveness))

When she says this is not possible, he says she is useless and cannot help him at all. She notices that she finds it hard to think in his presence, and forgets to check his observations, which is something she would always do.

(Finding it hard to think could be a projection of Henry’s sense of helplessness)

He is referred to the liaison psychiatry team. The psychiatrist discusses the case with the nursing staff prior to seeing Henry. The two nurses looking after him have different experiences and opinions of him. One feels sorry for him, and warmly towards him, and speaks about the meticulous care and attention he gave his wife when she was on the ward. The other also recalled him from that time, but experienced him differently. He seemed to find fault with everything she did and often sent her out of the room. She was almost afraid to nurse him now he was a patient.

(This could be projection and splitting) Projection – we can see he was projecting his own feelings of inadequacy and helplessness into the geriatrician (who was left feeling useless and unable to think). Into some of the nurses he engendered feelings of disgust, perhaps hate even and in others warmth. It’s important to note projections are not all negative. And even more important to remind ourselves they are not conscious. They are a form of unconscious communication.

Projective identification – would have occurred if the person who was being projected into then acted in the way they were being encouraged to do, for instance if the nurses who felt disgust, disdain, then withheld basic acts of care for Henry, or were punitive, (for example leaving him a long time without answering the call bell)

Something which suggests to us that projections may be occurring is the existence of splitting – this is a extreme form of black and white thinking, where parts of the self are experienced as so disparate and unintegrated that they are seen as completely disconnected. In Henry’s case the good caring parts were projected into some staff and experienced as coming from them, whilst other staff were experienced as cruel and withholding. Again we should be mindful that these are not conscious processes, although they may feel so.

A phone call to his GP revealed that Henry had never agreed to be seen for carer support, though often visited his GP with a minor complaint which usually lead into a discussion about the difficulties of caring for his wife, which often left the GP feeling angry and frustrated, but Henry seemed to leave feeling better.

(This could be a narcissistic defence, eg: illusion of self-reliance)

The psychiatrist found Henry withdrawn, but seemed to be emanating a rage. Henry was quick to dismiss her as being too young, not knowing anything. Henry snapped that psychiatrists never did any good – not for his wife, nor his mother.

The psychiatrist noted that it was hard to like Henry, and hard to think at all, even during the long periods of silence. She felt as if she was walking on eggshells and he would find fault with everything she said. Finally after a long period of silence she said “It must make you angry, this stoma, the cancer. It feels very unfair.”

(A common therapeutic tool is to name a feeling, in order to signal that it is manageable and open up a space for thought rather than just feeling and action)

Henry shuddered briefly “Of course I’m angry, wouldn’t you be? I spent all those years with my wife’s mess, now I have to clean up my own. Or have people I don’t know do it for me. It’s demeaning. When my wife was in hospital I did everything for her. Who is here to look after me?”

(This could be projection and transference, which we will explore further later)

Over the course of a 40 minute interview Henry spoke about how hard it had been caring for his wife. She has been clinically depressed for many years before developing dementia. He was quick to say that he had always taken good care of her. The psychiatrist commented that this was what the nursing staff recalled too. Henry seemed flattered that anyone had remembered this. He then spoke about his role in the Alzheimer’s Society, that he had helped others in caring, and never needed help himself and had always run carer’s groups and workshops. After his retirement, he had devoted himself entirely to care for his wife.

(We could speculate that this was compensation for ambivalent feelings towards his wife)

The psychiatrist asked at one point what he had meant when he had talked about when he said that psychiatry had never helped his mother. Henry bristled at this question but he answered briefly that his mother had had depression through his childhood. He had to learn how to cook at a young age, and clean for his father, as well as attending school, which he quickly added he did very well at. The psychiatrist commented that he must have had to grow up very quickly, be self-sufficient. Henry softened for a moment and then abruptly said, “So am I mad? Are you going to section me?”

(We could observe here that what is being done is containing and enabling some processing of his feelings and experiences. Even in the offer of observation and tentative interpretation, the psychiatrist is signalling that Henry’s feelings are important and held in mind. Assessments can be therapeutic.)

The psychiatrist explained she wasn’t going to do that, and merely wanted to find a way to ensure he was getting the best care, and support, given how hard it is for anyone, to have cancer, to deal with a stoma. He huffed and suggested the nurses could start by doing their jobs. The psychiatrist said she wondered if given the adjustments he was going through, the difficult times he had already been through with his wife, whether he might want to have the opportunity to talk some more. He declined though said speaking with her hadn’t been as bad as he had expected. They agreed that he would continue to see his GP. As the interview ends he requests to see the stoma nurse again.

The psychiatrist develops a working formulation, aspects of which are shared with the MDT.

Working Formulation

Henry hadn’t had much opportunity in his youth to experience attentive parenting, which helped him to moderate and understand his emotions. Normal emotions like rage, fear, joy, desire were felt as states which did not make sense, and were perhaps even destructive forces to be protected against. He may have even had an unconscious belief that he caused his mother’s depression. He spent his life attempting to repair the damage he felt he had caused to her by marrying a woman who also suffered mental illness, and caring for her. Caring for someone also allowed him to project his own weakness and need into someone else, and to not have to confront it. Even after his wife’s death – which too, may have many emotions attached to it – perhaps ambivalence, anger at her for leaving, resentment at her dependency. He quickly managed this by channelling all of his energy again into helping others – which some would see as good and important work (and it is) but for Henry perhaps it was more than that. It allowed him to see others as needy and weak, and he would remain strong, helpful, competent.

When faced with his own illness this meant he was no longer able to defend himself against his own dependency, weakness, his need to rely on others, and he became depressed. We can also see that the defences displayed whilst on the medical ward were those of:

This more detailed version of the formulation is akin to the more technical terminology used in other parts of medicine – like a histology or radiology report, which wouldn’t be shared with patients as they stand and might need interpretation for colleagues.

Management

What elements of the formulation would you share with the MDT?

- Henry may not have received consistent care in his earlier life

- He may find it therefore difficult to make sense of his emotions

- He has found himself taking on a caring role in his adult life

- Receiving care is hard for him

- He may be experiencing shame, fear and anger

- He might tend to experience different staff as all good or all bad

- The psychiatrist might also support staff to recognise how difficult it can be to provide care

Rather than referral for psychotherapy, the goal of the liaison intervention was to support the medical and surgical teams to best manage his care.

How do they translate the parts of the formulation into practice?

The nurses approach him in a supportive way:

- Ask permission, normalising what they were doing in terms of personal care

- Giving him more opportunities to talk about his life and his achievements

- Countering his own casual expressions of disgust and shame

- They are able to reflect on his presentation (and thereby avoid reacting without thinking)

- They are mindful of what might lie behind his anger

The surgical registrar explains to Henry the rationale for the stoma.

Henry consents to an OT and social work assessment and shared with the OT his experiences of caring for his wife.

This idea of containment is on by Wilfred Bion. He theorised the emotions of childhood being contained by the caregiver, who does not retaliate or become overwhelmed by them, and is able to return the emotion as a moderated, understood and tolerable experience, providing a unconscious model for the child to do this for themselves. In professional caregivers, the capacity to register emotional communications and process them, reflect and think allows them to care responsively (Waddell, 2002).

Staff act in this case as a container for the projected feelings of disgust, resentment, shame. Rather than enact these (eg; dismissal, avoidance, hate, cruelty or perpetuating the shame) they were able to accept them as communications from Henry.

Listeners may know of the work of Balint who recognised that GPs often act in containing patients, sometimes with medically unexplained symptoms, in this way, - with consistent care, and resisting the temptation to act rather than think about the patient. Balint recognised that this kind of work demands reflection and support.

The Wounded Healer: managing feelings of love and hate

“Being with patients can be very hard work. If we deny that as a fact, we are in trouble, because then we build our defences against the difficulty of the work.” – Tim Dartington, psychoanalyst (quoted in the forward of (Ballatt & Campling, 2011)

It’s important to talk about this notion which considers the unconscious life and motivations of people choosing healthcare as profession. People may be driven in this work to deal with unresolved hopes, hurts and fears (Ballatt & Campling, 2011)

Unconscious motivation to work with older adults may lie in desire for reparation; repair of previous important relationships or fear of our own destructive impulses. Inevitable failures to heal or cure risks repeating previous experiences and lead to burnout or depression.

The nature of the work itself is also challenging on a number of levels. Nursing in particular involves some very difficult work with people who often need very personal care - taking on some of the patient’s difficult emotions, and waste products. Staff defences against this can be a form of mindlessness, or detachment. Psychodynamic theory reminds us to consider what unconscious, defended feelings and motivations might underlie our responses to patients.

Concepts that are useful here include those of transference and countertransference. Transference describes the transfer of feelings from a primary relationship (usually a parental figure) onto a current relationship which can stem both from patients and clinicians. There is a tendency to repeat past relationships or dynamics.

Positive feelings towards patients, such as compassion, sadness and concern are all acceptable and encouraged in health care professionals. Negative feelings may be disavowed due to them being unacceptable with our professional identities (feelings like anger, frustration, resentment, guilt and hate, wanting to rid ourselves of patients in some way, for example: wanting to discharge a patient we are unsure how to help). The presence of these feelings can be sign of unconscious transference. Burying these feelings can be more destructive to patients and ourselves.

Winnicott developed important work on this subject - in 1949 “However much he loves his patients he cannot avoid hating and fearing them and the better he knows the less hate and fear will be the motives determining what he does to his patients” (Winnicottt, 1949).

So how might we take further our understanding of psychodynamic approaches?

- Personal analysis (useful if people feel they have particular issues, or have an interest in psychodynamic thinking)

- Clinical supervision (though not all supervision is likely to have a psychodynamic element – supervisor dependent)

- Reflective practice groups (there may be one on your ward, or speak to psych liaison/local psychotherapy department about organizing one?)

- Schwartz rounds – (pros – whole organisations can get involved, cons- can be impersonal)

- Balint groups – available for GPs and medical students (in some places).

- Professional development - Core to role of the medic and other health professionals, is development of emotional intelligence, and self awareness, thinking about your impact on them theirs on you. These are not adjuncts to the core role of being a doctor.

- Association for Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy in the NHS – Older Adults Section

Questions to ask to begin to think psychodynamically:

- How does it feel to be with this patient? And what might this tell me about their experience?

- What is not being said? And how are past patterns of behaviour or relating being repeated?

- How might this person’s early life shape their experience of caring or being cared for?

- How might thinking about these things help me to better care for them?

Summary:

We have spoken today about some of the fundamental ideas within psychoanalytic theory – the unconscious, repetition of patterns of relating, reparation, transference, defence mechanisms. The context in which older adults are cared for is something of a perfect storm, psychodynamically involving loss, dependency, and the need for personal care. Some of these ideas also apply to interactions with families, whose feelings may also be projected into professional carers and the institution. Families may play an important role in pointing out genuine failures of care, but they may also bring unconscious feelings such as guilt and anger. Navigating the balance can help to tease out what lies beneath these communications. We hope that people listening can understand that when we are under pressure professionally, we might have a tendency to engage superficially and logically, but the psyche operates a different logic. Attending to unconscious communications from ourselves, patients and families can resolve problems earlier and create a better environment for caring, and indeed a better experience for patients and staff.

Curriculum Mapping:

This episode covers the following areas (n.b not all areas are covered in detail in this single episode):

| Curriculum | Area | |

| NHS Knowledge Skills Framework | Suitable to support staff at the following levels:

| |

| Foundation curriculum | Section

1.2 3.10 | Title

Delivers patient centred care and maintains trust Recognises,assesses and manages patients with long term conditions |

| Core Medical Training | The patient as central focus of care

Confusion, Acute / Delirium Aggressive / Disturbed Behaviour Memory Loss (Progressive) | |

| PA matrix of conditions | Dementia | |

| Higher Specialist Training in Geriatric Medicine | 3.2.2 Common Geriatric Problems (Syndromes)

33 Dementia 42. Psychiatry of Old Age 49. Dementia and Psychogeriatric Services | |

| GPVTS program | Section 3.05 - Managing older adults

| |

| ANP (Draws from KSF) | Section 7.21 - Dementia |

1 Response

[…] a podcast with geriatricians Iain Wilkinson and Jo Preston this month, we explained the approach a liaison psychiatrist might take to a more complex case utilising […]