Episode 3.06 Identity & Ageing

Presented by:

Dr Iain Wilkinson (Consultant Geriatrician East Surrey Hospital)

Dr Jo Preston (Consultant Geriatrician St George’s Hospital)

Jackie Lelkes (Social Work Lecturer at University of Brighton)

Dr Tapiwa Moffatt (Clinical Fellow, East Surrey Hospital)

Faculty:

Sarah Jane Ryan (Senior Lecturer in Physiotherapy, Eastbourne)

Broadcast date: 25th April 2017 Click here for a downloadable PDF version of this infographic

Broadcast date: 25th April 2017 Click here for a downloadable PDF version of this infographic

CPD log

Click here to log your CPD online and receive a copy by email.

Episode 3.06 Identity and Ageing – Show Notes

Click here for a PDF version of the show notes

Learning Outcomes

Knowledge:

- Identity in the ageing process

Skills:

- To explore the development of and changes to a persons identify through the ageing process

- To consider theories of ageing

Attitudes:

- To understand how ageing impacts on identity

- To understand how older people may view the ageing process and the impact on their identity

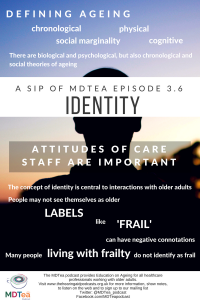

Definitions: When does old age begin?

WHO uses > 65 years Definitions in literature:

- Physical/biological decline in the body – including references to a lack of strength, difficulty in getting up, concern about broken bones, and an increase in aches and pains.

- The “cognitive decline” interpretative repertoire constructs ageing as involving memory loss or forgetfulness and no longer taking on mental challenges.

- The “social marginality” interpretative repertoire constructed aging as becoming subject to discrimination.

- Ageing constructed as a natural process or inevitable fact of life, i.e., as something that simply happens, but also as something that requires adaptation or may even be transcended.

Randall, W. and Kenyan, G. 2001. Ordinary Wisdom: Biological aging and the journey of life. London: Praeger.

Key Points from Discussion

Theories of ageing Theories of ageing link to various different constructs which might help to define adults as old or not.

- Biological: certain illnesses, disabilities or physical limitations make you old – links to frailty model

- Psychological: as old as you feel, mental attitudes

Several studies have shown that older adults who have more positive attitudes about their own ageing tend to perform better on memory tasks (Levy, 1996 and Levy and Langer, 1994), are more likely to engage in positive lifestyles (Levy & Myers, 2004), show less decline in disablement processes (Levy et al., 2012), and live longer (Levy et al., 2002). The findings from the latter studies suggest that attitudes toward one’s own ageing do not necessarily have to be negative, but can also focus on positive aspects of the ageing process, such as personal growth, increase in experience, or personal accomplishments. Individuals reflect on their own development and interpret their ageing as they move across the life span. In early and middle adulthood, the subjective experience of age takes a different direction and individuals report feeling younger than their calendar age. Rubin and Berntsen (2006) have argued that from midlife on, individuals feel about 20% younger than their actual age.

- Chronological: at x age you are old

- Social: based on your situation and those around you. Link to cohort ageing i.e. dynamic and time sensitive. For example, older adults now will not ‘behave’ the same as those in 20 years time – different experiences e.g. grandparents for child care, sandwich generation.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) suggests that the average retiree can look forward to drawing their pension for up to 24 years – as much as 50 per cent longer than their parents’ generation.

Frailty as a label

- Oxford English Dictionary definition: “ a fault and infirmity with both physical and moral dimensions”

- Report by Age UK identified frailty as a term associated with end of life, cancer and high levels of functional dependence.

Frailty can be seen as a negative label, and a term associated with giving up. There is growing evidence of antipathy to the term from older people, policy makers and non-specialist clinicians. The label of frailty is actively resisted, older people distinguishing between ‘the body one is’ (self identity) and the ‘body one has’ – a physical, vulnerable and objectified social identity. We need to be aware that labelling a person as frail can lead to stereotyping a person as failing to age well, a view which can be internalised by the individual. A WHO report on Ageing and Health (2015) defines frailty as “extreme vulnerability to endogenous and exogenous stressors that expose an individual to higher risk of negative health related outcomes”.

Staff attitudes are important

Nicholson et al suggest that the barriers to maximising independence during a hospital admission are the attitudes and behaviours of care staff. They noted that rarely were pre-admissions level of capability sought, and CGA’s did not always take account of the strategies a person had developed to deal with their vulnerabilities and self-perceived strengths. Care interventions focus on problems and incapacities, which can lead to increased levels of frailty.

Themes of Ageing

Functional – finding a role

Activity theory asserts a positive relationship between activity and life satisfaction: suggests that the greater the loss of activity, the lower the life satisfaction. Havighurst’s (1963) Activity Theory – discusses the role of engaging in different activities for wellbeing in old age. The framework proposes that the social and psychological needs of older adults, such as preference and needs for activities, are continuous across the adult lifespan. According to the theory, it is important that the elderly population maintains activities of middle-aged adults to achieve successful ageing and to protect its well-being. Carrying out an activity often implies the achievement of personal goals and offers channels for sustaining a positive self-concept, self-validation, and a sense of competence. An active lifestyle might give older adults an opportunity to socialize, to meet other people with similar interests, and to maintain personal relationships with friends and families. A longitudinal study explored how engaging in seven activities related to depression and quality of life 2 years later. These activities are (1) Volunteering (2) Providing help to neighbours, friends or family members (3) Taking part in political or community organizations (4) Attending educational courses (5) Going to the sports/social clubs (6) Taking part in religious organizations; and (7) Caregiving for disabled/sick adults. The research found that an active lifestyle was found to improve well-being, especially in those who were the most vulnerable at baseline. Therefore, intervention programmes and preventive measures should stimulate engagement in community and leisure activities. However, it is important that such programs take into account what motivates the older individual.

Potocnik et al.,(2013)

Critical – finding a role

- Political economy: ageing is a public, not a private issue. Focuses on links to economic life. E.g. when no longer contributing, then old age.

- Feminist theories: older theories based on male model being the primary worker. Accumulate disadvantage over life time: less time in work, less pay, less pension, longer life expectancy.

- Social construction: culture > chromosomes. Experience is dependent on how others react to older adults i.e. social context and cultural meaning are important.

Culture and Identity

Successful ageing: avoidance of disease, disability, high functioning and socially engaged. This is culturally specific to the West. Also, what about those who don’t? This imposes normative/youth values. With the growth of cultural gerontology interest has grown in ageing as the product of the interplay between bodily and cultural factors – particularly prevalent in the area of ‘appearance’ (see below).

Body Image

The ageing process is often associated with unwelcome changes in body image, increased dependency on others and negative societal stereotypes. Older women often have a sense of injustice in their ageing experience, recounting external pressures from society about appearance that were different for ageing men. The literature has a tendency to come from a number of discourses:

- The discourse of personal control/choices about how to live life i.e. exercise/cosmetic surgery.

- Social construction of identity i.e. the way the media portrays older persons impacts on perception of self and how wider society perceive them, for example seen as ‘a burden on the NHS.

- Societal and individual attitudes toward ageing include affective, cognitive, and evaluative components of behaviour toward older adults as an age group and toward the process of ageing as a personal experience (Hess, 2006). Attitudes toward ageing are considered critical for older people’s adjustment and survival. Bennett and Eckman (1973)

An online study in the US gathered survey-based information about body image, health, and ageing from women over age 50 and identified the following themes:

- Dissatisfaction with physical changes particularly during or after the menopause

- Societal pressure to look and dress a certain way and “act your age”.

- Experience with ageism: identified the real and perceived judgements women felt were made about the just because of their age i.e. the use of language to describe older woman and the inequalities in the way older men and women are treated in society.

- The importance of self-care: stressed the importance of healthy eating and regular exercise. A number discussed the importance of having realistic health goals.

- Invisibility: the survey highlighted than many mature women feel invisible, “not to be seen and not to be heard”.

- Need for recognition: older woman want to be heard and valued as a member of society.

Clinical Implications:

- Supportive discussion around ageing sends the message to patients that their needs are being taken seriously, which may promote disclosure of age-related challenges and enhance the therapeutic relationship.

- Because midlife and older women feel irrelevant, invisible, and discriminated against due to their age, professionals must pay attention to their own biases when working with ageing women, ensuring that assessment and treatment protocols are appropriately tailored, and should include images and magazines in health-care offices that show authentic women of all ages.

- Women found ageism in the language used by others. Thus, it is important that individuals and the media avoid age-related stereotypes when talking about middle-aged and older women.

- The presence of women of all ages and sizes in the media may also help women to feel seen, appreciated, and valued, which may reinforce their contribution to society. A conscious effort needs to be made, by the media, to be inclusive of all body types and not to put external pressure on middle-aged women to maintain a specific younger appearance.

Body image, aging, and identity in women over 50: The Gender and Body Image (GABI) study

Hofmeier et al., 2016.

Media representations One way to identify ageing is via portrayal in the media i.e. held responsible for problems with the NHS/burden to the younger generation. A study by Lemish and Muhlbauer (2012) identified how older women are represented in TV and films originating in the United States. They noted that older women are underrepresented and therefore largely invisible; when they do appear, they are stereotyped as:

- the controlling mother;

- the plain, uneducated, but good housewife;

- and the bitch–witch older woman.

Supporting the claim that the cultural discourses related to ageing devalue older women and offer them limited identities. Constructs of Ageing:

| Construct | Definition | Unidimensional measure | Multidimensional measure |

| Subjective age | The age an individual feels like or views him or herself | Single-item question (“How old do you feel?”; e.g., Barrett, 2003) | Physical/look age and social-emotional/feel age (Kastenbaum et al., 1972) |

| Age identity/age identification | A person’s subjective sense of age as a consequence of his or her various social experiences, including age-graded social roles, social identifications, conceptions of the life course, and socioeconomic conditions | Preferred or ideal age, Identification with age group (e.g., Barak, 2009); single-item question (see Barrett, 2003; “How old do you feel?”) | Felt age, other age, desired age, desired longevity, perceived old age (Kaufman & Elder, 2002) |

| Self-perceptions of aging | Self-perceptions of aging are anchored in the personal experiences of the individual, are multidimensional in nature, and are processed at a pre-conscious, implicit level with the potential to be consciously and explicitly expressed if a conducive context is provided | N/A | AgeCog scales (Steverink et al., 2001; Wurm et al., 2007) |

| Attitudes toward aging and age stereotypes | Affective, cognitive, and evaluative components of behavior toward older adults as an age group and toward the process of aging as a personal experience (Hess, 2006); includes both societal as well as individual attitudes | Attitudes toward Aging Subscale of the Philadelphia Geriatric Center Morale Scale (Lawton, 1975) | Attitudes to Ageing Questionnaire (AAQ; Laidlaw, Power, Schmidt, & the WHOQOL-OLD Group, 2007) |

| Age stereotypes are a specific subset of aging-related attitudes and beliefs, namely those attitudes and beliefs that give rise to prejudice and discrimination (e.g., ageism and ageist behavior; Levy, 2003) | Domain-based age stereotypes (Kornadt & Rothermund, 2011) | ||

| Awareness of Age-Related Change (AARC) | “All those experiences that make a person aware that his or her behavior, level of performance, or ways of experiencing his or her life have changed as a consequence of having grown older (i.e., increased chronological age)” (Diehl & Wahl, p. 340) | N/A | AARC Questionnaire (Diehl and Wahl, 2010 and Diehl et al., 2013) |

Awareness of aging: Theoretical considerations on an emerging concept. Developmental Review

Diehl et al., 2014

Resources

| Curriculum | Area |

| NHS Knowledge Skills Framework | Suitable to support staff at the following levels: Personal and people development level 1-3 Service improvement level 1 Equality and Diversity level 1-2 |

| Foundation Curriculum 2012 | 2.1 Treats patient as centre of care 2.2 Communication with patients 6.1 Lifelong learning |

| Foundation Curriculum 2016 | 2. Patient centred care 4. Self-directed learning 6. Communication with patients/relatives/carers 10. The frail patient |

| Core Medical Training | Common competences:

System specific competences:

|

| GPVTS program | Section 2.01 The GP Consultation in Practice

Section 3.05 – Care of older adults

|

| ANP (Draws from KSF) | Section 20. The patient as central focus of care Section 32. Frailty Section 35. Psychological, social, cultural, ethnic and economic factors |