Episode 2.6 – Depression

MDTea Episode 2.6 – Depression in Older Adults

In this episode we explore depression in older adults. We talk about how it may present in older adults in various ways, to various people. What features differ in older adults and what you can do to help.

this episode we explore depression in older adults. We talk about how it may present in older adults in various ways, to various people. What features differ in older adults and what you can do to help.

Broadcast date: 1st November 2016

Click to download this sip of MDTea

Presented by: Jo Preston (Consultant Geriatrician at St George’s Hospital) and Iain Wilkinson (Consultant Geriatrician at East Surrey Hospital).

Core Faculty: Pam Trangmar (Physician Associate at East Surrey Hospital), Tracy Szekely (Occupational Therapist at University of Brighton).

Guest Faculty: Dr Victoria Osman-Hicks (Consultant Old Age Psychiatrist in Southampton).

Here are some resources you might find useful to use and share with the person you are treating and their families:

The Royal College of Psychiatrists has a factsheet for patients and their relatives: http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/healthadvice/problemsdisorders/depressioninolderadults.aspx#

Some resources you might want to recommend to help with self management include:

- Mind over Mood – book

- Overcoming Depression – book

- MoodGym – a computer based CBD program

CPD log

Click here to log your CPD online and receive a copy by email.

Episode 2.6 – Depression – Show Notes

(Click here to download)

Learning Outcomes

Knowledge

- To be able to define and recognise a depressive disorder (depression)

- To be able to distinguish between normal sadness and adjustment (adjustment disorder) from a depressive episode (depression in lay terms)

- To be aware of the evidence based treatments available in a stepped care model.

Skills

- To be aware of useful screening and severity rating tools such as the Geriatric Depression Scale and use in clinical practice.

Attitudes

- To be able to support an older person with depressive symptoms in an empathic and understanding way.

What is Depression?

- ‘a disorder marked by great sadness, apprehension, feelings of worthlessness and guilt, withdrawal from others, loss of sleep, appetite and sexual desire, as well as loss of interest and pleasure in usual activities and either lethargy or agitation’ (Davidson & Neal, 2001, p. G5).

Davidson, G. C. & Neale, J. M. (2001). Abnormal Psychology (8th ed., p. G5). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- It may be the result of illness and/or physical changes associated with old age or it may also be the result of experiencing difficulty adapting to new or changed circumstances, stress, changes in social relationships, loss, and social adjustment particularly in old age (Lichtenberg, 1998)

Lichtenberg, P. (Ed.). (1998). Chapter 3: The role of depression in geriatric health outcomes. Mental Health Practice in Geriatric

Health Care Settings (pp. 37–52). New York: The Haworth Press.

- Standard definition of Depression (ICD-10)

-

- persistent sadness or low mood;and/or

- loss of interests or pleasure

- fatigue or low energy

- at least one of these, most days, most of the time for at least 4 weeks

-

-

- if any of above present, ask about associated symptoms:

- disturbed sleep

- poor concentration

- low self-confidence

- poor appetite with weight loss

- suicidal thoughts or acts

- agitation or slowing of movements

- guilt or self-blame

- if any of above present, ask about associated symptoms:

ICD 10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders

The 10 symptoms then define the degree of depression and management is based on the particular degree

> these symptoms of low mood must be present for most days, persistently, for at least 4 weeks<

- not depressed (fewer than four symptoms)

- mild depression (four symptoms)

- moderate depression (five to six symptoms)

- severe depression (seven or more symptoms, with or without psychotic symptoms)

Note that a comprehensive assessment of depression should not rely simply on a symptom count, but should take into account the degree of functional impairment and/or disability

Mood Assessment is a key part of the CGA process and the CGA may identify the factors influencing a low mood and which may be modifiable.

NICE suggest that we should all be alert to depressive symptoms and they suggest these two questions:

- During the last month, have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed or hopeless?

- During the last month, have you often been bothered by having little interest or pleasure in doing things?

If a person answers yes to either of these then a mental health assessment should be carried out (or the patient referred for one should you not be able to do this).

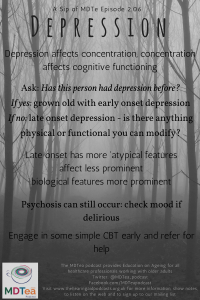

In older people that have depression – around a half will have had depression in their younger life already. People with impaired cognition are more likely to develop depression. Some of the common symptoms seen in younger life are less common in depression in older people (Affect symptoms less prominent with biological features more prominent (sleep, eating, etc.), there may be cognitive changes, and low motivation and participation in therapies / self care). Psychosis is still a part of presentation (and depression can be part of a differential diagnosis for delirium).

Co-existent dementia makes the diagnosis harder and treatment options may be less clear:

Study (HTA-SADD) looking at placebo and two commonest prescribed anti-depressants in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and found no difference at 13 or 39 weeks.

Depression assessment tools

Firstly good clinical assessment along the lines of that described in the NICE guidelines is key. Some screening tools though may help with the assessment.

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – ADS was found to perform well in assessing the symptom severity and caseness of anxiety disorders and depression in both somatic, psychiatric and primary care patients and in the general population.

The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review.

Geriatric Depression Score

Available in a 30 and 15 point score. Both valid as a screening tool for depression

The short form of the Geriatric Depression Scale: a comparison with the 30-item form.

What can we all do?

Group therapy facilitates social interactions may well help – often centered around learning a new skill

CBT – works in older adults

- For mild-moderate depression

- There is now computer based CBT like ‘MOODGYM’ – mixed evidence for benefit over standard GP care but works for some

CBT all HCPs can do

- Activity scheduling:

- identify with the person a few things they would like to do, set targets starting with the easiest (must be achievable)

- such as making a cup of tea for spouse, unloading the dishwasher, posting a letter/going for a short walk, phoning an old friend for a chat, reading a newspaper etc.

- Set as ‘homework’ and follow up how patient’s gets on and how it makes them feel.

- Consider wider things that may help mood

- exercise, physio for poor mobility,

- analgesia for back pain,

- psycho-education course on a long term condition (e.g. stroke/cardiac rehab)

- Get families to support and encourage, avoiding them undermining the approach or taking over which may increase feelings of helplessness or encourage a sick role/illness behaviour.

- Recommend a book on prescription/ available at most libraries such as Mind over Mood, Overcoming Depression (see those at the top of the show notes).

Drug therapies

- in depression generally the more severe the more effective the medications – Lancet 2009 meta-analysis.

- Not recommended for use in mild depression or short lived symptoms (e.g. adjustment disorder)

Systematic review showed refractory depression (defined as failure to respond to at least one course of treatment for depression during the current illness episode) found that half of participants responded to second line drug therapy.

- Older people = >55y.

- No RCTs

- Only drug studied in more than one study was lithium.

Electro-convulsive therapy

- Course of treatments , usually twice a week for 6-20 session under a very short anaesthetic.

- Effective treatment for depression but reserved for refractory cases or where there is a risk to life (such as when a person is not eating and drinking) and there is not time for an antidepressant to take effect.

- It can bring about fairly rapid improvements in depression and mania.

- Followed by long term medication to help prevent relapse.

- Usually done in a few ECT suites in psychiatric units or in acute hospital theatres.

- Uncommonly some patients have ‘maintenance’ ECT at intervals such as 2-4 weekly to maintain their recovery.

Curriculum Mapping:

This episode covers the following areas (n.b not all areas are covered in detail in this single episode):

| Curriculum | Area |

| NHS Knowledge Skills Framework | Suitable to support staff at the following levels:

|

| Foundation Curriculum 2012 | 1.3 Continuity of care

1.4 Team working 2.1 Patient as centre of care 8.6 Manages acute mental disorder and self-harm 10.5 Health promotion, patient education and public health |

| Foundation Curriculum 2016 | 2. Patient centred care

4. Self-directed learning 10. Management of long term conditions in the acutely unwell patient 10. Support for patients with long term conditions |

| Core Medical Training | Common competences:

Symptom specific competences:

System specific competences:

|

| GPVTS program | Section 2.03 The GP in the Wider Professional Environment

Section 3.05 – Managing older adults

Section 3.10 Care of People with Mental Health Problems

Understand the difference between depression and emotional distress, and avoid medicalising distress. Understand the place of instruments in case-finding for depression.

Understand the importance of recognising and treating depression and anxiety in people with long-term physical illnesses |

| ANP (Draws from KSF) | Section 6. Clinical examination

Section 7.21 Dementia, depression, anxiety Section 9. CGA process Section 11. Decision making and clinical resourcing Section 25. Legislation- Mental Health Act |

| PA Matrix of conditions | Category 1A

Category 1B

|

| Paramedic Curriculum | C 2.3.6 Mental health, including: psychosis, depression. |