9.02 Peripheral Vascular Disease

Presented by: Iain Wilkinson, Jo Preston, Alice O’Connor

Broadcast Date: 4th February 2020

BONUS AUDIO!

Full interview with Professor Christian Heiss now available:

Social Media

Iain: Practices to Foster Physician Presence and Connection With Patients in the Clinical Encounter

Learning Outcomes

Knowledge

- To be able to describe the symptoms that an older person may present with if they have PVD

- To understand the difference between arterial and venous disease and how they present.

Skills

- To be able to explain PVD to a patient and outline the initial investigations

Attitudes

- To understand the impact of PVD on a patient and the potential impact of this on their lifestyle.

CPD Log

Show Notes

Definition

Formal definition

We often talk of PVD – it’s a risk factor for many things and is included in a number of frailty assessments and things like the CHADsVASC score etc… but what actually is PVD?

Peripheral arterial disease is defined as obstruction of blood flow to areas except the coronary and cerebral vessels. However in this episode we are going to focus on the lower limb arterial disease and not really cover aortic disease or venous disease.

Among older adults the incidence and prevalence of all PVD increases. This is due to age-related alterations in vascular structure and function which are compounded by longer exposure to cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors.

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology (2016) 13: 727732

There are a number of conditions associated with the development of PVD:

- Atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis is the buildup of plaque inside the artery wall. Plaque is made up of deposits of fatty substances, cholesterol, cellular waste products, calcium, and fibrin. The artery wall then becomes thickened and loses its elasticity. Symptoms may develop gradually, and may be few, as the plaque builds up in the artery. However, when a major artery to the heart or brain is blocked, a heart attack or stroke may occur.

- Buerger disease (thromboangiitis obliterans). This is a chronic inflammatory disease in the arteries. It leads to blood clots in the small- and medium-sized arteries of the arms or legs, eventually blocking them. This disease most commonly occurs in men between ages 20 and 40 who smoke cigarettes. Symptoms include pain in the legs or feet, clammy cool skin, and a diminished sense of heat and cold.

- Chronic venous insufficiency. This is a prolonged condition in which 1 or more veins don’t adequately return blood from the legs back to the heart. It’s due to valve damage in the veins. Symptoms include discoloration of the skin and ankles, swelling of the legs, and feelings of dull, aching pain, heaviness, or cramping in the legs.

- Venous thromboembolism (VTE). This term is used to describe 2 conditions, DVT and PE. They use the term VTE because the 2 conditions are very closely related.

- Raynaud phenomenon. This is a condition in which the smallest arteries that bring blood to the fingers or toes tighten when exposed to cold or during emotional upset. It most commonly occurs in women between ages 18 and 30. Symptoms include cold, pain, and paleness in the fingertips or toes.

- Thrombophlebitis. Thrombophlebitis is a blood clot in an inflamed vein, most often in the legs, but it can also occur in the arms. It may result from pooling of blood, injury to the vein wall, and changes in how the blood clots. Symptoms in the affected extremity include swelling, pain, tenderness, redness, and warmth.

- Varicose veins. Dilated, twisted veins are caused by valves that allow backward flow of blood. This allows blood to pool. It’s most commonly found in the legs or lower trunk. Symptoms include bruising and sensations of burning or aching. Pregnancy, obesity, and extended periods of standing make symptoms worse.

Practical definition

Essentially: Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is a common condition where a build-up of fatty deposits in the arteries restricts blood supply to the leg muscles.

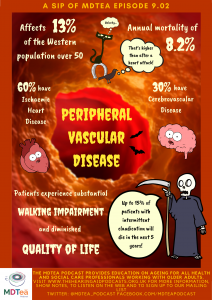

Patients with PAD experience substantial walking impairment and diminished quality of life due to symptoms of limb ischemia as well as increased cardiovascular disease (CVD) morbidity and mortality.

The hallmark of PAD is claudication – exercise-induced lower limb ischemia distal to the site of arterial occlusion that is relieved within 10 minutes of rest. Claudication symptoms are often described as pain, fatigue, numbness, or weakness in the hips, buttocks, thigh, or calf that is alleviated with rest.

Based on a limited number of trials, there is a difference between men and women in the manifestation or experience of PAD symptoms. Women report a higher prevalence of leg pain at rest or with exertion, lower functional capacity, impaired walking ability, worse self-reported quality of life and physical functioning compared with men with PAD.

Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing Vol. 21, No. 5S, pp S15YS20

This article gives a really good review of the cardiovascular changes which occur as we age, but the key findings are:

(NERD ALERT)

Arterial changes include: increased calcium deposition, collagen content and collagen cross-linking; increased vessel diameter and outward remodeling; increased reactive oxygen species and a pro-inflammatory state; and increased apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells.

Other changes include: alterations in endothelial function, neurohormonal regulation and renal function; and venous stasis with laxity in large venous valves. The cumulative impact of these vascular processes lead to unique physiology and vulnerabilities of older adults, which are commonly manifest in target organ damage and vascular disease.

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology (2015) 12: 196−201

Main Discussion

How common is it?

Really quite common – around 13% of the western population over the age of 50years old.

In 2010, PAD defined as ABI ≤0.9, affected 202 million subjects worldwide; this number increased by 22% to 237 million in 2015.

As we have seen it is most commonly due to atherosclerosis and the stenosis that occurs related to this – leading to a reduction in blood flow to the affected limb. Most patients are asymptomatic, but many experience intermittent claudication (pain on walking).

A key point is that atherosclerosis is a systemic disease.

- 60% of patients with peripheral artery disease will have ischaemic heart disease

- 10-15% of patients with intermittent claudication will die from cardiovascular disease within 5 years.

- 30% have cerebrovascular disease.

Therefore, management begins with identification and modification of risk factors that are common to peripheral artery disease, heart disease, and stroke.

Who is at most risk?

The BMJ article makes the point that two large population studies found that over 95% of patients have at least one cardiovascular risk factor.

Smoking

- Results from a systematic review of 17 studies including 20 278 patients suggest that half of all peripheral artery disease can be attributed to smoking.

- Heavier smokers are more likely to develop peripheral artery disease than light smokers and that former smokers have a persistently increased risk compared with never smokers

Diabetes

- The TASC II (Trans-Atlantic Inter-Society Consensus Document on Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease (TASC)) guidelines conclude that, for all patients with diabetes, the relative risk of developing peripheral artery disease is similar to that of people who smoke.

- A prospective cohort study of 1894 diabetic participants found that poor diabetes control was associated with an increased risk of peripheral artery disease.

- Patients with diabetes are more likely to be asymptomatic because of the co-existence of neuropathy in a substantial proportion. Peripheral artery disease in this population is more likely to be found in more distal vessels in the calf.

- Population studies have found that around half of patients with a diabetic foot ulcer have peripheral artery disease.

Other

- The prevalence of peripheral artery disease increases with advancing age; one population study of 2174 participants found an increase from 1% of 40-49 year olds to 15% of those aged over 70. The same study found that black ethnicity increased the risk of peripheral artery disease (odds ratio 2.83, 95% confidence interval 1.48 to 5.42). This difference persists after correcting for conventional risk factors.

- TASC II guidelines conclude that men are affected at a younger age than women, but overall there is no clear distinction in risk.

- They also concluded that high fasting serum cholesterol level, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease each increase in the risk of peripheral artery disease by 1.5 times. Peripheral artery disease is also associated with high serum homocysteine.

What is the impact?

Asymptomatic disease is a marker of sedentary lifestyle rather than less severe disease and outcomes are similar to those with claudication. Up to 25% of symptomatic patients will need intervention, but fewer than 5% will progress to critical limb ischaemia.

Within five years from diagnosis of peripheral artery disease, the risk of amputation is 1-3.3% and all-cause mortality is 20%

Patients have a reduced quality of life when compared with coronary heart disease.

Ann Vasc Surg. 2002 Jul;16(4):495-500. Epub 2002 Jun 27.

Additionally if you have visual impairment it is associated with an increased risk of falls – an example of how conditions can compound each other.

J Am Geriatr Soc 66:1934–1939, 2018

How to make the diagnosis?

History – suggestive of PAD or DM and non-healing wounds or unexplained pain in the legs

Symptoms in common vascular presentations:

- Intermittent claudication

- Claudication in calf, thigh, or buttock

Critical limb ischaemia (When the reduction in blood flow is so severe that it causes pain on rest or tissue loss (ulceration or gangrene))

One or more of:

- Ulceration

- Gangrene

- Rest pain in foot for >2 weeks

Acute limb ischaemia

Sudden onset of one or more of*:

- Pain

- Pallor

- Pulseless

- Paraesthesia

- Paralysis

- “Perishingly” cold

- Sudden deterioration of claudication

*Not all of the “six Ps” need to be present for diagnosis

Examining:

- The legs and feet for ulceration, temperature differences between the legs, muscle atrophy, and skin changes (for example thin, shiny skin, discolouration, dependent rubor and elevation pallor, tissue loss on the heel or between the toes, hair loss).

- Femoral, popliteal, and foot pulses.

- Capillary refill time (although this may not be reliable).

- The cardiovascular system (including for arterial bruits — femoral, aortic, carotid).

Assess people with suspected peripheral arterial disease by measuring the ankle brachial pressure index (ABPI). This should be undertaken by an experienced operator using validated equipment.

If an experienced operator using validated equipment is not able to detect an ankle pulse on Doppler, consider the possibility of acute limb ischaemia (see Features of acute limb ischaemia) and seek immediate advice from a vascular specialist.

With the person resting and supine (if possible):

- Record systolic blood pressure with an appropriately sized cuff in both arms and in the posterior tibial, dorsalis pedis, and, where possible, peroneal arteries.

- Take measurements manually using a Doppler probe of suitable frequency in preference to an automated system.

- Calculate the index in each leg by dividing the highest ankle pressure by the highest arm pressure.

An ABPI ratio of less than 0.9 indicates the presence of peripheral arterial disease (with some classifications using a threshold value of less than 0.5 for critical limb ischaemia), but a resting ABPI of more than 0.9 does not mean that peripheral arterial disease is not present.

- If lower extremity artery disease is clinically suspected, a normal ABPI does not exclude the diagnosis — if there is any doubt about the diagnosis, seek advice from a vascular surgeon.

- If the ABPI is high (1.4 or more), consider the possibility of peripheral arterial disease, particularly if the person has diabetes. Do not exclude a diagnosis of peripheral arterial disease in people with diabetes based on a normal or raised ankle brachial pressure index alone.

NICE Guidelines – Peripheral Arterial Disease

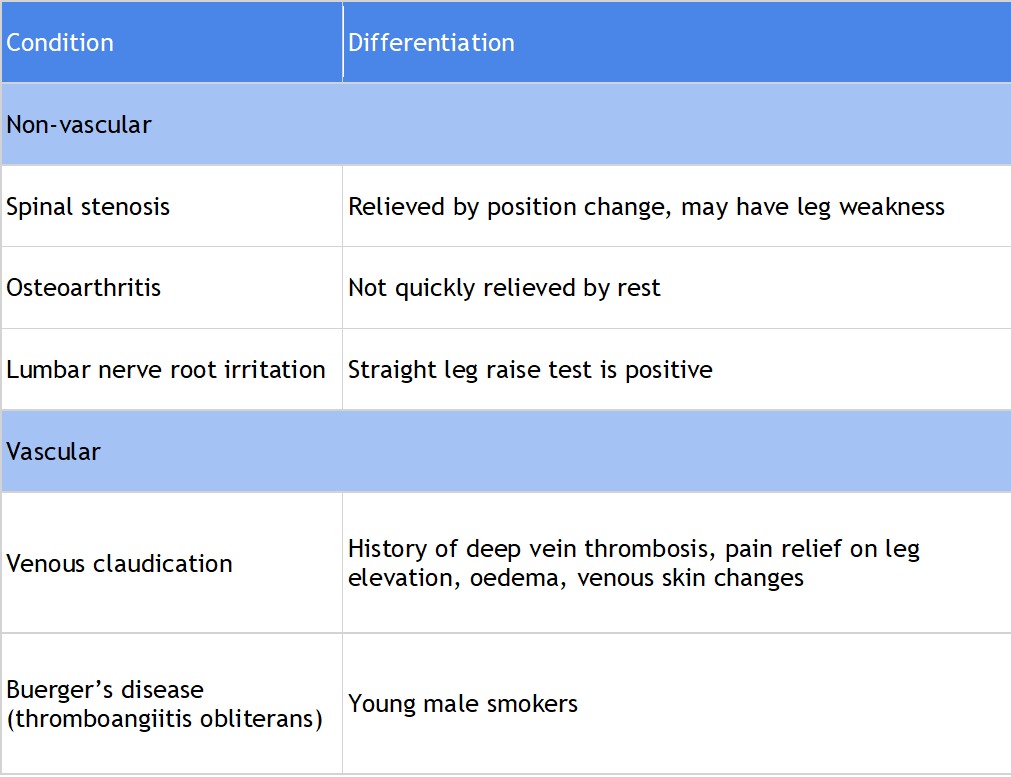

Differential Diagnoses

How to manage PAD?

NICE Guidelines – Peripheral Arterial Disease

- If available, offer a supervised exercise programme to all people with intermittent claudication.

- This may involve two hours of supervised exercise a week for a 3-month period and encouraging people to exercise to the point of maximal pain.

- If supervised exercise is not available, consider suggesting unsupervised exercise (using clinical judgement and taking into account the person’s motivation and comorbidities).

- For example advise exercise for approximately 30 minutes three to five times per week, walking until the onset of symptoms, then resting to recover.

[There is however debate over this..]

“While supervised exercise training is a mainstay of the management of claudication, low adherence rates limit its clinical application.

In a randomized study, 156 participants were allocated to supervised treadmill exercise, supervised resistance training, or oral advice about nutrition and training. After 6 months, the 6‐min walk distance improved only in the treadmill exercise group (36.1 m, 95% CI 13.9–58.3), but at 12 months neither treadmill nor resistance significantly differed from baseline or control (walking distance: +7.5 m and +6.1 m). These results highlight the need for long-term supervised exercise programmes to maintain benefits.

Additionally, a systematic review of 84 studies reported that alternative training modalities (circuit exercise, low-pain and pain-free walking, resistance training, upper/lower limb ergometry, and pole striding) had significantly higher adherence and completion rates vs traditional exercise training (85.5% vs. 77.6%, and 86.6% vs. 80.8%, respectively).“

- Refer for consideration of angioplasty or bypass surgery when:

- Advice on the benefits of modifying risk factors has been reinforced, and

- A supervised exercise programme has not led to a satisfactory improvement in symptoms.

- Consider prescribing naftidrofuryl oxalate if supervised exercise has not led to a satisfactory improvement, and the person prefers not to be referred for consideration of angioplasty or bypass surgery.

- Review progress after 3–6 months and discontinue naftidrofuryl oxalate if there has been no symptomatic benefit.

Also aggressive management of risk factors if appropriate:

- Smoking cessation therapy

- HbA1c control (target value <48 mmol/mol)

- Blood pressure control (target <140/90 mm Hg*)

- Clopidogrel (or aspirin) 75 mg lifelong (no additional benefit from Ticagrelor in a recent study. (Circulation 2019;140:556–565.)

- Atorvastatin 80 mg lifelong

Curriculum Mapping

NHS Knowledge Skills Framework

- HWB2 Level 1

- HWB6 Level 1

Foundation Programme

- Sec 1:4 Self directed learning

- Sec 3:10 Long term conditions in unwell pt

- Sec 3:16 (all)

GPVTS

- 3.05 Clinical management

- 3.05 Managing medical complexity

Core Medical Training

- Managing long term conditions and promoting patient self-care

- Rehabilitation and MDT

- Health promotion and public health

- Lifestyle

- Other Important Presentations

- Immobility

- Geriatric Medicine

- MDT assessment

- Rehabilitation targets

- Preventative approach

Internal Medicine Stage 1

- Geriatric medicine

- Deterioration in mobility

- Cardiology

- Limb pain

- Diseases of the arteries, including aortic dissection

- Public health and health promotion

- Exercise

- Smoking

Geriatric Medicine Specialty Training

- Managing long term conditions and promoting patient self-care

- Rehabilitation and MDT

- 29. Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Disease and Disability

- 30. Rehabilitation and Multidisciplinary Team Working