8.01 Sarcopenia

Presented by: Dr Iain Wilkinson & Dr Jo Preston

Core Faculty: Sarah Jane Ryan, Dr Dan Thomas

Guest input: Dr Richard Dodds – many thanks for the advice and guidance

Release date – August 13th 2019

Social Media

Iain: Parkinsons TV

Learning Objectives:

Knowledge

- To understand and define the term sarcopenia.

- To be able to explain the potential treatments for sarcopenia

Skills

- To be able to diagnose sarcopenia

- To be able to talk to your patients about things they can do to ‘treat’ sarcopenia

Attitudes

- To think about the holistic management in frail patients all the time

- To encourage healthy activities in patients of all ages.

CPD LOG

Show Notes

Part 1: Making the diagnosis

Recap on frailty cycle.

Good review in the Lancet.

Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Sayer AA. Sarcopenia. Lancet. 2019 Jun 29;393(10191):2636-2646.

Formal definition

In 2010, the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) published a sarcopenia definition that was widely used worldwide; this definition fostered advances in identifying and caring for people at risk for or with sarcopenia.

In early 2018, the Working Group met again (EWGSOP2) to determine whether an update to the definition of sarcopenia was justified.

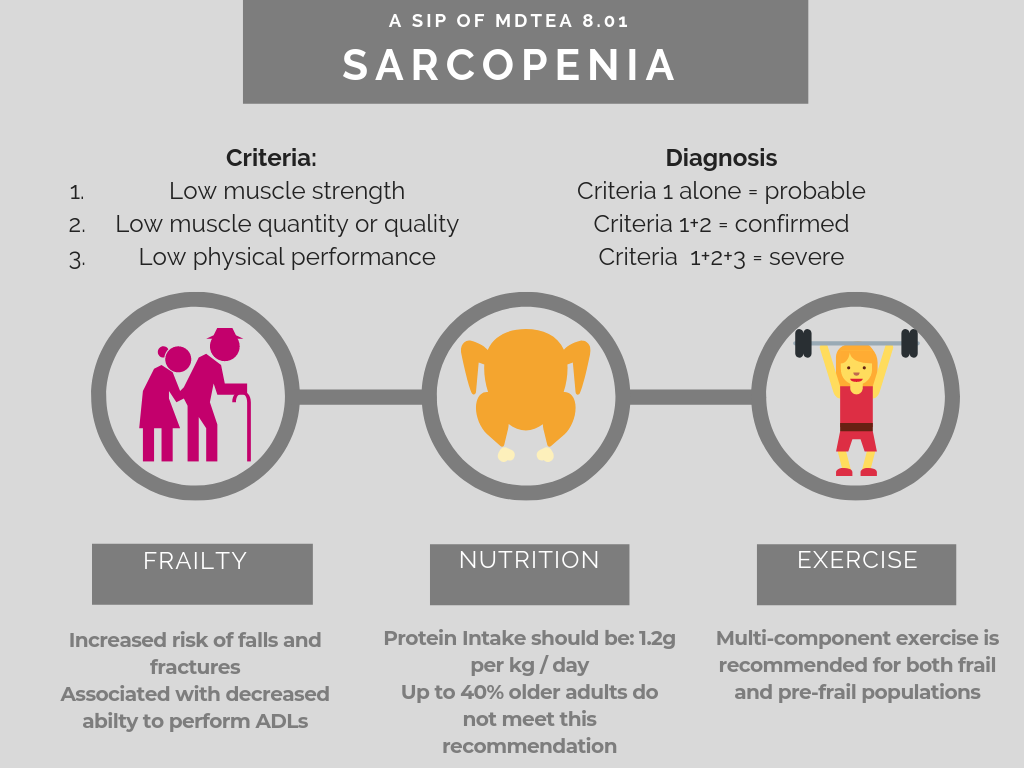

Effects of Sarcopenia

In terms of human health:

- increases risk of falls and fractures

- impairs ability to perform activities of daily living

- is associated with:

- cardiac disease

- respiratory disease

- and cognitive impairment

- leads to mobility disorders

- and contributes to:

- lowered quality of life

- loss of independence or need for long-term care placement

- death

In financial terms:

- The presence of sarcopenia increases risk for hospitalisation and increases cost of care during hospitalisation.

- Among older adults who are hospitalised, those with sarcopenia on admission were more than 5-fold more likely to have higher hospital costs than those without sarcopenia.

- Key points from the 2018 meeting:

- First: Sarcopenia has long been associated with ageing and older people, but the development of sarcopenia is now recognised to begin earlier in life, and the sarcopenia phenotype has many contributing causes beyond ageing.

- Second: Sarcopenia is now considered a muscle disease (muscle failure), with low muscle strength overtaking the role of low muscle mass as a principal determinant.

- Third: Sarcopenia is associated with low muscle quantity and quality, but these parameters are now used mainly in research rather than in clinical practice. Muscle mass and muscle quality are technically difficult to measure accurately.

- Fourth: Sarcopenia has been overlooked and undertreated in mainstream practice apparently due to the complexity of determining what variables to measure, how to measure them, what cut-off points best guide diagnosis and treatment, and how to best evaluate effects of therapeutic interventions]. To this end, EWGSOP2 aims to provide clear rationale for selection of diagnostic measures and cut-off points relevant to clinical practice.

2018 operational definition of sarcopenia

3 Criteria:

- Low muscle strength

- Low muscle quantity or quality

- Low physical performance

- Probable sarcopenia is identified by Criterion 1.

- Diagnosis is confirmed by additional documentation of Criterion 2.

- If Criteria 1, 2 and 3 are all met, sarcopenia is considered severe.

Practically:

Practical definition

- In clinical practice, case-finding may start when a patient reports symptoms or signs of sarcopenia (i.e. falling, feeling weak, slow walking speed, difficulty rising from a chair or weight loss/muscle wasting). In such cases, further testing for sarcopenia is recommended.

- EWGSOP2 recommends use of the SARC-F questionnaire – self reported 5 item questionnaire.

Practically it’s possible to measure:

- Muscle strength

- Muscle quality

- Physical performance

Part 2 – Protein intake and nutritional management of sarcopenia

- Daily reference (RNI) for protein for adults is 50g or 0.75g of protein per kg bodyweight per day for adults

- RNI (reference nutrition intakes) is the amount of nutrient required to ensure 97.5% of peoples needs are being met

- 32%- 41% women and 22%-38% men older than 50 eat less than the recommended dietary allowance (when cut off of 0.8g/kg/day used)

- Difficult to apply a population level recommendation to an individual

- Older people can produce less muscle protein than younger people from the same amount of protein in diet

- Evidence that older adults in particular when they are unwell have higher protein requirements (guidelines are that protein intake should increase in this situation: up to 1.2 – 1.5g/kg)

PROTAGE study recommends average protein intake at least in range of 1 – 1.2g protein to help older people maintain and regain lean body mass.

- A protein intake as high as 1.6g/kg/day shown to increase muscle hypertrophy with exercise in older adults

- But hospital menu often have much less protein than this, national catering and nutritional specification for food and fluid provision in hospitals in Scotland (https://www2.gov.scot/resource/doc/229423/0062185.pdf) suggest if over age 50 then 53.3g protein per day needed if male and 46.5g day if female

- Spread protein equally through out day shown to help – also around the time of exercise

- Weak evidence that leucine enriched balanced amino acid diets and creatinine supplementation can help treat sarcopenia – being looked at in the LACE study

References on nutrition:

https://www.jamda.com/article/S1525-8610(13)00326-5/fulltext

Part 3 Exercise

General exercise guidelines for older people have recently been updated through the Royal Osteoporosis Society – it is worth a general read but is not specific for sarcopenia.

A recent review…June 2019 (McLeod) included:

“most physical activity guidelines advise, as their primary message, that older adults should perform at least 150 min of moderate-to-vigorous or 75 min of vigorous AET (aerobic) weekly for the reduction of chronic disease risk and maintenance of functional abilities”

American College of Sports Medicine, 2009; Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology, 2011; American Heart Association, 2018; Piercy et al., 2018

However, there is an emerging body of evidence to suggest that RET (resistance) can be as effective as AET in reducing chronic disease risk and is particularly potent for maintaining mobility in older adults

Tanasescu et al., 2002; de Vries et al., 2012; Grontved et al., 2012; Stamatakis et al., 2018

- Lots of useful discussion in this paper and helpful to consider the role of resistance exercise within more comprehensive exercise training.

- This links well to another recent review Jadczak et al (2018).

This umbrella review aimed to determine the effectiveness of exercise interventions, alone or in combination with other interventions, in improving physical function in community-dwelling older people identified as pre-frail or frail.

Effectiveness of exercise interventions on physical function in community-dwelling frail older people an umbrella review of systematic reviews.

Results:

Seven systematic reviews were included in this umbrella review

58 relevant randomized controlled trials and 6927 participants.

Five systematic reviews examined the effects of exercise only, while two systematic reviews reported on exercise in combination with a nutritional approach, including protein supplementations, as well as fruit and dairy products.

The average exercise frequency was 2–3 times per week (mean 3.0 ± 1.5 times per week; range 1–7 weekly) for 10–90 minutes per session (mean of 52.0 ± 16.5 mins) and a total duration of 5–72 weeks with the majority lasting a minimum of 2.5 months (mean 22.7 ± 17.7 weeks).

Multi-component exercise interventions can currently be recommended for pre-frail and frail older adults to improve muscular strength, gait speed, balance and physical performance, including resistance, aerobic, balance and flexibility tasks.

Resistance training alone also appeared to be beneficial, in particular for improving muscular strength, gait speed and physical performance. Other types of exercise were not sufficiently studied and their effectiveness is yet to be established.

Conclusions:

Interventions for pre-frail and frail older adults should include multi-component exercises, including in particular resistance training, as well as aerobic, balance and flexibility tasks.

Future research should adopt a consistent definition of frailty and investigate the effects of other types of exercise alone or in combination with nutritional interventions so that more specific recommendations can be made.

Another umbrella review published this year concludes

“Since sarcopenia is affecting all skeletal muscles in the body, we recommend training the large muscle groups in a total body approach. Although low-intensity resistance training (≤50% 1RM) is sufficient to induce strength gains, we recommend a high-intensity resistance training program (i.e. 80% 1RM) to obtain maximal strength gains.”

Exercise Interventions for the Prevention and Treatment of Sarcopenia. A Systematic Umbrella Review. J Nutr Health Aging. 2019;23(6):494-502. doi: 10.1007/s12603-019-1196-8.

Curriculum Mapping

NHS Knowledge Skills Framework

- Core 1 level 2

- Core 2 level 2

- Core 4 level 1

- HWB1 level 2

- HWB2 level 2

- HwB4 level 3

- HWB7 level 1

Foundation Programme

- Section 1.4. Keeps practice up to date through learning and teaching – Self Directed Learning

- Section 3.10 – 10. Recognises, assesses and manages patients with long term conditions – The Frail patient and Nutrition

Core Medical Training

- Geriatric Medicine

- History taking (nutritional intake)

- Weight Loss

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Public Health & Health Promotion

GPVTS

- 3.01 Healthy People: promoting health and preventing disease – Nutrition

- 3.05 Care of Older Adults

- 3.17 Care of People with Metabolic Problems

Geriatric Medicine Specialty Training

- Principle Objectives: 1) Perform a comprehensive assessment of an older person, including mood and cognition, gait, nutrition and fitness for surgery in an in-patient, out-patient or community setting, including day hospitals

- 3.2.3 Presentations of Other Illnesses in Older Persons – Weight Loss

- 3.2.9 Health Promotion – Nutrition

- 29. Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Disease and Disability – Sarcopenia

- 37 Nutrition

- 44 Care of Older People living with Frailty

Physician Associate Matrix of Conditions

- N/A