10.7 Grief

Presented by: Iain Wilkinson, Jo Preston, Sophie Norman

Broadcast date: 08/06/2021

Social Media

Learning Outcomes

Knowledge

- To know of some of the ways of classifying/staging grief are

- To learn about ‘complex’ or ‘atypical’ grief reactions and the risk factors for developing these

Skills

- To be able to identify ways to intervene or provide support to people experiencing loss

Attitudes

- To have an awareness of how bereavement may affect older people uniquely

- To acknowledge the unique experience of grieving for a loved one with dementia

CPD Log

Show Notes

Definitions

Bereavement: a state of loss, or the period time after the loss of a loved one

Grief: a bio-psycho-social response/reaction to a bereavement.

ie; referring to the psychological components of bereavement: the feelings evoked when a loved one dies

Independent Age, Good grief report: Older people’s experiences of partner bereavement

Main Discussion

“The study of grief is first and foremost a study of love and of the attachments humans create in their lifetime”

(Colin Murray Parkes, Psychiatrist and former chairman/now life president of the charity Cruse bereavement care)

Theories of grief and how we might classify and describe it

- The Kubler-ross stages of grief

These stages have been widely taught over the last few decades, and are;

- Denial

- Anger

- Bargaining

- Depression

- Acceptance

Elizabeth Kubler-Ross, was a Swiss-American psychiatrist, and put forward the stages in her book on death and dying.

- Widely taught to health care professionals working with people experiencing loss

- This is not a prescriptive process, and people do not necessarily progress through the stages in a step-wise fashion or experience all of the stages

Criticism of the model

- That not everyone experiencing bereavement experiences each element

- It may not be beneficial in identifying those at risk of atypical or prolonged grief reactions

- The model does not help significantly in the designing of services/support

- It is not based on empirical evidence

However….

- It’s also argued that the model provided a vocabulary for people to use to discuss death and dying, something that was not the case at the time it was introduced in western culture.

- Kubler-Ross didn’t advocate for strict following of the ‘stages’

- The model began a shift in culture, moving away from the ‘medicalisation’ of death by those in the healthcare profession.

Some suggest that perhaps it is best to view the stages in the context of the experience of the individuals she interviewed, acknowledge the criticisms of the model but also value her emphasis on active listening, and her focus on the patients experiencing terminal diagnoses and loss themselves.

- Worden (2009) suggested the following 4 things may need to occur to enable an individual to adapt to loss:

- acknowledging the reality of the loss;

- working through the pain and emotional turmoil that follow the loss;

- finding a way to live meaningfully in a world without the one who is gone; and

- Loosening the bonds to the deceased while embarking on a new life

(taken from: Clark, E. Loss and Suffering: the role of social work. Available at:

https://www.socialworker.com/feature-articles/practice/loss-and-suffering-the-role-of-social-work/)

Other theories of grief do exist (stroebe and schut, silverman and klass)

- And another way of looking at the grieving process – as a timeline:

Independent Age, Good grief report: Older people’s experiences of partner bereavement

Prolonged grief disorder, or complicated grief (disordered grief, pathological grief)

Included in the WHO ICD-11, to take effect from January 2022.

Risk factors:

- Past history of depression and anxiety

- Nature of relationship to the person who has died (increased risk if deceased is a spouse or child)

- How the person died – sudden or traumatic deaths

- Lack of social support

- Hospital and ICU deaths

- Lack of preparation for the death

- This is a condition separate to depression, PTSD and attachment/separation disorders/anxiety

- For eg, depression may make people feel their feelings are muted, or they do not long for/yearn for things. In PGD, emotions are often heightened.

- Characterised by longing for, and preoccupation with the deceased, and emotional distress and significant functional impairment lasting for more than 6 months after the loss.

Given the need for this to be internationally applicable, cultural variations are accounted for/cultural caveats included.

- Eg timeframe – in germany, a period of mourning for a year (‘trauerjahr’) is culturally accepted, and the symptom profile might vary from culture to culture.

While it might be assumed that older adults will cope better with grief, a recent literature review identified similar proportions of older adults experiencing PGD, compared with younger ones, at about 1 in every 10 people experiencing loss.

Current treatments for CGD include CGT (complicated grief therapy), delivered by trained psychotherapists. This focuses on acceptance of the loss, connecting with memories, and thinking about the future, amongst other things.

Relevant to the COVID -19 pandemic

Factors which may make the grief/bereavement different/more difficult:

- Isolation

- Remote conversations with HCPs

- Loved ones dying alone

- Multiple deaths

- Unable to visit, or unable to travel

- Unable to perform cultural rituals

An argument made by Morris et al in a 2020 article talking about bereavement and loss during the pandemic is that bereavement support should be seen as a public health measure, and a preventative intervention. They acknowledge bereavement support is not universal in hospitals and should be provided prior to and after a loss to avoid complex grief reactions.

This sentiment was echoed in a survey published in the BMJ by Pearce et al: it was of UK health and social care workers, which reported that the pandemic had caused major problems in the delivery of bereavement support, and identification of those who might need it, as well as access to specialist care and support for those experiencing complicated grief reactions. They concluded that bereavement care and support needs to be seen as an integral part of health and social care provision.

What makes grief different for older people?

Loss of a partner/siblings/friends puts older people in the majority of those experiencing grief.

- There were 603000 deaths in the UK in 2015 (85% of those in >65 year olds)

- The number of bereaved older people is set to increase by more than 100,000 people in the next 20 years, from 192,000 in 2014 to 294,000 newly bereaved people every year by 2039

- More than 200,000 older people will lose their partner this year.

Older adults are less likely to both seek and receive help and support in grief

They are also more likely to experience multiple bereavements in a relatively short period of time

They are less likely to have received formal support from hospice/pall care services than younger people – which worsens the experience of grief

Independent Age, Good grief report: Older people’s experiences of partner bereavement

What wider effects can grief have, aside from the emotional, psychological and spiritual impact/pain that the loss causes?

For the ‘older old’ (>85) grief compounds existing age related problems

- Isolation

- Independence/dependence

- Poverty

Men and women

- Men experience more isolation.

- Women experience financial and practical difficulties

Isolation

Nearly a third of bereaved people over 65 see themselves as very lonely, compared to just 5% of people of the same age who have not lost their partner.

More than 1 in 5 people said that loneliness was the hardest thing to cope with after the death of their partner.

Older people who are carers for their dying partner are at greater risk of feeling lonely both before and after their partner dies.

Independent Age, Good grief report: Older people’s experiences of partner bereavement

Sleep

Poor sleep is associated with grief

One study from this year looking at middle aged and older aged people found an association between poor sleep (in many forms) and grief

- Poor efficacy of sleep

- Shorter overall time sleeping

- Longer time to fall asleep

- Waking for long periods of time after falling asleep

The study continued to follow people over time, and those with less sleep at baseline, tended to experience longer or more complicated grief reactions

Partner loss

This, and child loss, is often felt to be one of the most difficult losses to bear.

There is a higher risk for developing a complicated grief reaction when a spouse/partner is lost than following the loss of a parent, for example.

Physical health and increased mortality after loss, is seen mainly after partner loss

- An old study, but with simple recommendations/points to consider;

- In men >75 in the first 6 months after partner loss, there were excess deaths recorded compared to men of the same age in the population

- Independent predictors for mortality in the sample studied were

1) interviewer assessment of low happiness level

2) interviewer assessed and self-reported problems with nerves and depression

3) lack of telephone contacts

More recently, and published in age and ageing in 2009, Anne Bowling looked again at data re mortality from the group of 361 older people widowed and interviewed in the 1980s.

- At the time of the original research, 6 month mortality was shown to be higher after loss in males >75.

- Over a longer period of time, this risk disappeared.

- While analysis of the data set up to 13 years had suggested socioeconomic factors and self reported psychosocial factors had an impact on mortality, at 28 years after the loss these factors were no longer independent predictors of mortality

- Independent predictors of mortality in the group of widows/widowers long term (up to 28 years) were older age, male sex, poorer physical functioning and interestingly interviewer assessment of ‘relief at death of spouse’

The true effect of the loss of a spouse on physical health/mortality is not entirely clear from the studies that we found when looking into this for the episode, with some reporting different outcomes.

However, risk of death after bereavement from CV causes does seem to be consistently reported

..and a 2007 study from scotland reporting increased relative risk of mortality in those bereaved vs those from cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, stroke, all cancer, lung cancer, smoking‐related cancer, and accidents or violence

This is not what was found by King et al in 2013, looking specifically at partners of people who had died from cancer, where interestingly the risk of death following the bereavement was less than non-bereaved counterparts.

LGBTQ+ experiences

- Lack of recognition as being the NOK in partner loss

- Reduced social support/family support

- Less likely to have children

- Legal and financial uncertainty (if not in civil partnership/marriage)

10.5 LGBTQ+ Older Adults – The Hearing Aid Podcasts

BAME experience of grief and loss

- Decisions re care/funerals etc in the country they live in vs country they were born in

- Large families/communities – number of connections not correlated with quality of connection/support

- Poverty

Dementia – a special case

The concept of ‘caregiver-burden’ has been well linked to stress, depression and grief amongst people looking after relatives/friends with dementia.

And a term ‘dementia grief’ has been coined by Blandin et al, overlapping with the idea of anticipatory grief, but encompassing things unique to the experience of looking after a loved one with dementia. They suggest 3 elements;

Compounded serial loss

- Build as the disease progresses

- May be small and large losses

- Eg loss of communication, withdrawal from activities

Ambiguous loss

- Lack of clarity, due to fluctuant nature of impairments, or to changing/lost characteristics, or to the fact that there is loss of function/capacity for some things (eg to reconcile over previous disagreements, or loss of particular memories), but not loss of the person themselves

Receding of the known self

- The loss of characteristics, personality, memories etc of the person with dementia, to the point at times when the person does not remember who the caregiver is

Risk factors for caregivers developing complicated grief after death of the patient with dementia

- Positive experience of delivering care

- High levels of pre loss depressive symptoms and burden

- Caring for a more cognitively impaired patient

People who received psychosocial interventions and support for depression and ‘burden’ had lower levels of psychiatric morbidity following their loss.

A 2007 paper from Sanders et al looking at people caring for a loved one with dementia identified 7 themes that were common to those who were deemed to be experiencing high levels of grief

- yearning for the past

- regret and guilt

- isolation

- restricted freedom

- life stressors

- systemic issues adding to caregiver stress

- coping strategies of religious groups, social groups and pets

Could we identify some of these things early and intervene to reduce morbidity?

How well do we support people?

ONS, National survey of bereaved people (VOICES) (2015-16)

One of the questions asked if family/friends got as much help and support from H+S care as was needed when caring for them in the 3 months prior to death

- For friends/relatives of patients >age 80, ~46 % said yes to this, 23% said some, but not as much as was needed, ~16 responded no, and said they had asked for more help, and 13% said no but that they had not requested more help.

- Pattern broadly similar for those looking after people in other age groups

- Interestingly, when splitting the results based on the age of the respondent, for people >60 years (ie the carers/friends/relatives, not the patient themselves), the responses were broadly more positive re receiving help needed, compared to those <60 years old.

- Interestingly (and this isn’t broken down by age of patient or respondant), for those who died in hospital vs home/hospice/care home the response to the same questions was more negative i.e. less felt they had had the support required.

For the question concerning whether the relative/friend/carer had had the chance to talk to people from health or social care or specialist bereavement services:

- Similar percentages in both groups of respondents (>60 and <60) said yes (~13%), with those over 60 responding ‘no, but I didnt want to anyway’ at higher rates than those under 60.

- For people whose relative/friend died in a care home, the lowest rate of people answered ‘yes’ (compared to hospice, hospital, at home)

- When the results were disaggregated by gender, men responded ‘no, but I did not want to anyway’ more than women, and women responded ‘no, but I would have liked to’ more than men.

Dataset:National Survey of Bereaved People (VOICES)

What can we do?

The NICE Quality Standard: End of Life Care for Adults touches on bereavement support:

- Quality statement: People closely affected by a death are communicated with in a sensitive way and are offered immediate and ongoing bereavement, emotional and spiritual support appropriate to their needs and preferences.

- It specifies the need to recognise particular needs of vulnerable groups eg those with LD

- It acknowledges local services should be developed with community, acute, voluntary and private organisations

- Support might include

- Practical eg funeral arrangements, what to do with medications/equipment

- Emotional

- Information about

9.08 Learning Disabilities in Later Life – The Hearing Aid Podcasts

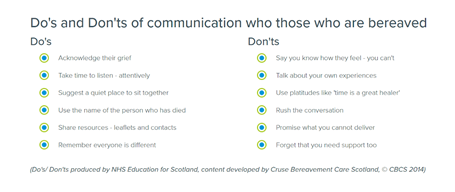

When it comes to talking to families/patients about loss Macmillan explains that listening, and acknowledging what has happened, and signposting to specialist resources is something everyone can do. They suggest considering the following questions

- What is this person coping with?

- What impact is it having on them?

- What resources do they have? How are they managing?

- Are there risk factors associated with their bereavement outcome?

Staff experiences of patient loss

- This can be a difficult thing to talk about

- This has been particularly difficult for everyone over the last year, but those looking after older people may have been really significantly affected, because of the nature of COVID-19 and the proportion of those who died being overwhelmingly in the older age bracket.

- Things to consider that have made it particularly hard

- Staff working in new environments, perhaps with dying patients when usually this is not something they do

- Lack of time to process grief and feelings of loss

- The unique experience of social care workers, or care home workers, who may have long term professional relationships with patients who have died

- Restrictions on family/friend visits

- The number of deaths witnessed/experienced

- Personal experiences of loss

There are some brilliant resources from macmillan, produced because of the pandemic but applicable at other times too;

They cover what bereavement and grief is, why things are harder in the context of the pandemic, what we can do for patients but also how to deal with personal losses, including that of colleagues. There is signposting to lots of resources, including ones tailored to specific situations and jobs.

They also cover emotional wellbeing, physical health, resilience, connectedness and personal growth in the context of bereavement – both giving background to why these things are important, and provide lots of resources like self-guided mindfulness exercises and information on accessing more formal/expert support.

NHS England also have some guidance for people in more senior positions, on looking after their staff in situations where there is loss and grief.

If there is anything this episode has affected you, we will include in the show notes links to resources that provide help and support – for you, for loved ones and for patients.

Resources and information if you are looking for more information or support (for your patients, or yourself)

From the NHS for staff:

And from the government, signposting to places of support:

Independent charities and groups:

https://www.cruse.org.uk/get-help/useful-links#Adult

https://www.cruse.org.uk/get-help/useful-links

https://www.mariecurie.org.uk/help/support/bereavement

https://www.nursingcenter.com/ce_articleprint?an=00000446-201907000-00025

Independant Age:

Age UK:

https://cariadlloyd.com/griefcast

https://www.openingdoorslondon.org.uk/who-we-are

Curriculum Mapping

NHS Knowledge Skills Framework

- level 3 Develop and maintain communication with people about difficult matters and/or in difficult situations

Foundation Programme

- Care after death, F1/F2

GPVTS

- Life stages topic guides – People at the end of life

- Financial implications for patients and their carers including access to benefits

- Approaches to supporting families and carers after bereavement need to take into account religious, spiritual and cultural beliefs and practices

- Care giver ‘pressure points and distress’

- Recognition of complex grief signs and symptoms (to align with changing ICD code)

Internal Medicine Stage 1

- Specialty CiP: Managing end of life and applying palliative care skills

- Palliative medicine and end of life care

Geriatric Medicine Specialty Training

- Clinical CiP 8: Managing end of life and applying palliative care skills

- Palliative Care