7.01 – Polypharmacy

Presented by: Dr Jo Preston, Dr Iain Wilkinson and Sam Lungu

Faculty: Dr Dan Thomas, Sam Lungu, Mairead O’Malley

Broadcast Date: 12th February 2019

In this episode we will be talking about how and why polypharmacy happens and think about some strategies and tools to aid safe deprescribing.

Learning Objectives

Knowledge:

To be able to describe what polypharmacy is and the impact it may have on patients

To know when to explore polypharmacy and deprescribing

Skills:

To be able to signpost patients to have their medications reviewed

To have a framework to structure you approach to ongoing medication use

To drive shared decision making in prescription management with older people

Attitudes:

Raise the awareness and get the public and patients engaged with the drive to reduce inappropriate polypharmacy.

To understand that there is a cultural shift needed in public awareness that multiple medicines in older age may cause harm.

Social Media this week…

https://twitter.com/dan26wales/status/1094704811390447621

Main Show Notes

What is polypharmacy?

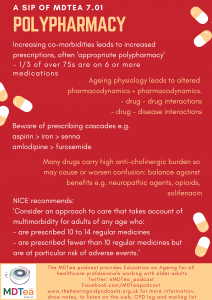

- Polypharmacy is when people are taking multiple medications.

- As people get older the number of medication they are prescribed can increase as they develop more and more medical conditions (indeed also the as the treatment of these conditions changes with time there may be more medications used – Average number of medications per person has increased by 54% in ten years)

- Due to changes in older peoples physiology then polypharmacy can become a problem and actually iatrogenesis is one of Bernard Issacs ‘geriatric giants’

- Definition of polypharmacy has changed over the years as the number of medications people take has increased, so more than 4 or 5 medications would have been considered polypharmacy

- The NICE guideline NG 56 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng56 on multimorbidity (which we have previously discussed on podcast episode 3.1) suggests that we:

- ‘Use an approach to care that takes account of multimorbidity for adults of any age who are prescribed 15 or more regular medicines, because they are likely to be at higher risk of adverse events and drug interactions.

Consider an approach to care that takes account of multimorbidity for adults of any age who:- are prescribed 10 to 14 regular medicines

- are prescribed fewer than 10 regular medicines but are at particular risk of adverse events.’

- ‘Use an approach to care that takes account of multimorbidity for adults of any age who are prescribed 15 or more regular medicines, because they are likely to be at higher risk of adverse events and drug interactions.

But the numerical definition of polypharmacy is not as useful as taking an approach when you decide whether someone has appropriate or inappropriate polypharmacy (often called problematic polypharmacy)

An example of appropriate polypharmacy may be a robust older person who has had a heart attack and now has heart failure, it may be appropriate for him to be on 7 or 8 different medications.

Some numbers:

- By 2018 3 million people in the UK will have a long-term condition people managed by polypharmacy

- The number of people on ten or more medication has increased from 1.9% to 5.6%

- A third of people aged 75 years and over are taking at least six medicines.

What are the consequences of polypharmacy?

- If a person is taking ten or more medicines they are 3x more likely to be admitted to hospital.

- Adverse drug reactions are responsible for 6.5% of hospital admissions

Interactions:

- Drug-Drug

- If people take multiple medications then there may be drug-drug interactions e.g. cholinesterase inhibitors and anti-cholingerics – we discussed this in episode on delirium 1.02.

- Drug – disease

- There are also drug – disease interactions, when a medication can make the management of another disease more difficult e.g. NSAIDS can make hypertension worse.

- It is very easy for people to end up taking multiple medications, especially when single disease guidelines are followed for an individual who has multiple diseases.

- With multimorbidity in particular, the number of drug-drug interactions can rapidly escalate.

- In one paper 12 single disease NICE guidelines were analysed and they found 133 potentially serious (drug-drug) interactions for the type 2 diabetes guideline, of which 25 (19%) involved one of the four drugs recommended as first line treatments for all or nearly all patients.

- and 32 potentially serious drug-disease interactions between drugs recommended in the guideline for type 2 diabetes and the 11 other conditions.

- Given that: “adverse drug events cause an estimated 6.5% of unplanned hospital admissions in the United Kingdom, accounting for 4% of hospital bed capacity” It makes it an area we should focus on!

- Complying with disease specific guidelines is difficult, a person with three chronic diseases takes six – thirteen different drugs a day, if people have six chronic conditions (COPD, ischaemic heart disease, osteoarthritis, hypertension, diabetes and depression) then the number of medications rose to 18 a day

Similar article also in Age and Ageing journal: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22910303

Prescription cascade

Something that we commonly see is a prescription cascade, where a medication has been started to treat the side effect of another medication e.g. furosemide is often started to treat the leg swelling (peripheral oedema) that has been caused by a calcium channel blocker such as Amlodipine.

https://twitter.com/OliviaSDON/status/914054374527311873 – cartoon about this

In addition to what has been discussed so far then there are some medications that can commonly cause problems specifically in older frailer people – such as medications with a high anticholinergic burden (discuss later), and medications that have a sedative effect such as diazepam or zopiclone.

Medication most associated with admission due to ADR

The most common medicine groups associated with admission due to ADRs were:

- Non-steroidal anti- inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) 29.6%

- Diuretics 27.3%

- Warfarin 10.5%

- Angiotensin-converting-

- enzyme (ACE) inhibitors 7.7%

- Antidepressants 7.1%

- Beta-blockers 6.8%

- Opiates 6.0%

- Digoxin 2.9%

- Prednisolone 2.5%

- Clopidogrel 2.4%

Worth noting that these are recognised adverse effect e.g. easier to recognise when a drug is causing an AKI, drugs that cause people to present with vague symptoms, frailty crisis etc may not be in the above list.

Why older people?

Older people are more sensitive to the adverse effects of polypharmacy due to some physiological changes which occur with ageing. NERD ALERT

- Absorption: Increased Gastric pH (sometimes due to medications such as proton pump inhibitors) due to atrophic gastritis. Decrease in gastric emptying.

- Distribution: Probably the main physiological change that occurs with ageing that leads to adverse drug reactions.

- Increase in body fat and decrease in body water (as a proportion of total body weight).

- Volume of distribution of fat soluble drugs increases so medications such as benzodiazepines accumulate due to increased elimination half life, so can still have an effect a long time after the medication has been stopped.

- Volume of distribution of water soluble drugs is decreased so water soluble drugs e.g. such as digoxin need a reduced loading dose.

- Altered permeability of the blood brain barrier so the brain of an older adult can be exposed to higher levels of medication causing cognitive adverse effects

- Metabolism

- Reduced hepatic blood flow can reduce clearance of medications that have high hepatic excretion ratio e.g. Amitryptiline.

- Relevant to polypharmacy in any age is the number of medications someone takes means it is more likely that they are taking an inducer or inhibitor of Cytochrome P450 increasing the chance of drug-drug interactions.

- Elimination/Kidneys

- As people age there is a reduction in renal mass and renal blood flow. eGFR decreases by 0.5% a year after age 20.

- Affects clearance of water soluble drugs such as diuretics, digoxin and NSAIDs.

Older people and drug trials

- Underrepresented

- When they are included often they are ‘healthy’ older people

- Frailty, multimorbidity, cognitive impairment, care home residents often an exclusion criteria

Anticholinergics

- 20-50% of older people prescribed at least one medicine with anti-cholinergic activity.

- Dry mouth and eyes, constipation, urinary retention, blurred vision, tachycardia

- Sedation, confusion, hallucinations, decline in cognitive and physical function

- 23% of people with dementia.s prescribed AC drugs.

- medicines with anti-cholinergic properties have a significant adverse effect on cognitive and physical function, but limited evidence exists for delirium or mortality outcomes.

How the ACB was made:

“We searched the Medline database from 1966 to 2007 for any study that measured the anticholinergic activities of a drug and evaluated the association between such activities and the cognitive function in older adults. We extracted from each study the method used to determine such activities and the list of medications with anticholinergic activities that were associated with negative cognitive effects, including delirium, MCI,dementia or cognitive decline. This list was presented to an expert interdisciplinary team that included geriatricians, geriatric pharmacists, geriatric psychiatrists, general physicians, geriatric nurses and aging brain researchers. Subsequently, the team categorized the above medications into three classes of mild, moderate and severe cognitive anticholinergic negative effects”

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/244933972_Impact_of_anticholinergics_on_the_aging_brain_A_review_and_practical_application [accessed Jan 02 2019].

ACB index itself:

https://www.alzheimer-riese.it/images/stories/files/Docs/ACB_scale_-_legal_size.pdf

Tools for managing de-prescribing

Which are the most important medications?!

http://www.cpsedu.com.au/posts/view/47/2016-Deprescribing-Resources

- Firstly why do we want to deprescribe, it may be for many older people living with frailty then they are not going to live long enough to benefit from medications that are being used for prevention purposes such as statins or antihypertensives.

- Should try and continue medication if it is providing day to day symptomatic relief such as analgesia, antianginals if get angina – broadly follow the principles from the multimorbidity guidelines to help with this:

Should not stop drugs such as antiseizure medication or drugs for parkinsons without very careful consideration and input from the relevant specialist.

Barriers to Medicines optimisation or Deprescribing

- Concern from clinicians to discontinue medications started by another provider

- Time expenditure

- Fear of drug-withdrawal side effects

- Lack of resources

- Resistance from patients or family members

- Fear of losing patient-provider relationship

Protocol to Medicines Optimisation or Deprescribing

- Ascertain all drugs patient is currently taking and reasons for each one

- Need patient (or family member) to bring all drugs (prescribed, complementary and alternative medications and OTC meds)

- Clarify how/when/if patient is taking medication

- Ask the patient if they have missed any doses recently:

- mention a specific time (such as in the past week),o explain why you are asking,

- ask about medicine-taking habits,

- do not apportion blame.

- Use the pharmacist to help! – perform med reconciliation (may involve contacting patient’s pharmacy, employing pill counts, etc)

- Consider overall risk of drug-induced harm in individual patients in determining required intensity of deprescribing interventions

- Assess for risk factors, including:

Number of drugs (single most important predictor)

| Past or current toxicity – Use of high-risk drugs | Age >65 years | Cognitive impairment/ dementia |

| Multiple comorbidities | Multiple prescribers | Past or current nonadherence |

| Renal impairment | Substance abuse | End of Life |

Useful Tools

STOPP START Toolkit

Supporting Medication Review STOPP:Screening Tool of Older People’s potentially inappropriate Prescriptions. START: Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right i.e. appropriate, indicated Treatments.

- Produced with a relatively small number of experts and consensus opinion via delphi process

Using this tool reduces improves prescribing:

- Unnecessary polypharmacy, the use of drugs at incorrect doses, and potential drug-drug and drug-disease interactions were significantly lower in the intervention group at discharge (absolute risk reduction 35.7%, number needed to screen to yield improvement = 2.8 (95% confidence interval 2.2-3.8)).

- Underutilization of clinically indicated medications was also reduced (absolute risk reduction 21.2%, number needed to screen to yield reduction = 4.7 (95% confidence interval 3.4-7.5)).

Beer’s criteria

Here – created a list of medications suitable for safe prescribing in older people. Started with an 11 member panel.

Updated in 2015

STOPP FRAIL

- A list of explicit criteria for potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) use in frail older adults with limited life expectancy.

- STOPPFrail comprises 27 criteria relating to medications that are potentially inappropriate in frail older patients with limited life expectancy. STOPPFrail may assist physicians in deprescribing medications in these patients.

The ‘NO TEARS’ tool

7 is a useful prompt to aid efficient medication review and maximise the potential of the 10 minute consultation

| N | Need and indication | Has the diagnosis changed? Was long term treatment intended? Is the dose correct? |

| O | Open Questions | Solicit the patients opinion and concordance |

| T | Tests and monitoring | Are further tests needed? |

| E | Evidence and guidelines | Is there a better approach to this illness now? e.g. new guidelines |

| A | Adverse Events | Consider iatrogenic problems (Side effects, drug interactions) |

| R | Risk reduction or prevention | Identify the individual patients risks |

| S | Simplification and switches | Simplify the regimen and implement cost effective switches |

Consultant Pharmacy Services – Tasmania

Address one of the key problems with the things we just talked about – you have to know something about the condition etc to make a choice with the patient. All well and good if you know everything(!) and understand the context, but for most of us it’s hard. These try to address that by looking at specific groups of medications and have produced an excellent series of factsheets for specific groups of medications.

- Allopurinol

- Antihypertensive Agents

- Antiplatelet Agents

- Antipsychotics for BPSD

- Benzodiazepines

- Bisphosphonates

- Calcium and Vitamin D

- Cholinesterase Inhibitors

- Glaucoma Eye Drops

- NSAIDs

- Opioids

- Proton Pump Inhibitors

- Statins

- Sulphonylureas

Useful resources

www.NNT.com

http://www.cpsedu.com.au/posts/view/47/2016-Deprescribing-Resources

Curriculum Mapping

This episode covers the following areas (n.b not all areas are covered in detail in this single episode):

- NHS Knowledge Skills Framework

- Personal and People Development: Levels 1-3

- Service Improvement: Level 1 – 2

- Communication: Levels 3-4

- HWB2 – level 3 + 4

- HWB3 – level 2 and 3

- HWB4, 5 and 6 – Levels 3 and 4

- IK2 – Level 3

- Foundation curriculum

- 10. Recognises,assesses and manages patients with long term conditions

- Management of long term conditions in the acutely unwell patient

- The Frail patient

- 13. Prescribes safely

- Core Medical Training

- Patient as central focus of care

- Geriatric Medicine – Rationalise individual drug regimens to avoid unnecessary polypharmacy

- Clinical Pharmacology

- Palliative Care

- GPVTS program

- 2.01 The GP Consultation in Practice – Clinical management – prescribing

- 3.05 Care of Older Adults

- 2.01 The GP Consultation in Practice – Clinical management – prescribing

- Geriatric Medicine Training Curriculum

- 3.2.1 Basic Science and Biology of Ageing

- 1. History Taking: recognise importance of verbal and non-verbal communication from patients and carers

- 3. Therapeutics and Safe Prescribing

- 6. Patient as the Central Focus of Care

- 7. Prioritisation of Patient Safety in Clinical Practice

- 11. Managing Long Term Conditions and Promoting Patient Self Care

- 43. Palliative Care

- Dementia care skills education and training framework

- Pharmacological interventions in dementia care – Tier 2

2 Responses

[…] in our episodes on multimorbidity and polypharmacy we saw that being treated by multiple specialist teams for multiple conditions leads to harm. There […]

[…] S7E1 – Polypharmacy […]