5.07 DOLS

Episode 5.07 – DOLS

Presented by: Dr Jo Preston, Dr Iain Wilkinson

Faculty: Jackie Lelkes, Pam Trangmar, Philippa Christie

Broadcast Date: 1st May 2018

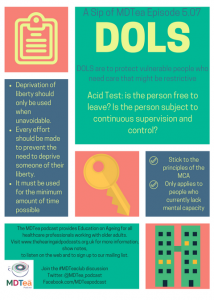

Click here for a pdf of the sip of MDTea poster

Click here for a pdf of show notes

CPD log

Click here to log your CPD online and receive a copy by email.

Tweetchat #MDTeaClub

We will be hosting a ‘journal club’ type tweet chat to discuss topics raised in this episode using #MDTeaClub

Join us to discuss topics raised in the episode and spread any resources you may have!

Social Media this week

Iain’s Pick:

But there are others… check out #thishastochange

Jo’s Pick:

Whatever happened to silence – Postgraduate medical journal 2018

Main Show Notes:

Learning Outcomes

Knowledge:

- To understand what might constitute a deprivation of liberty

- To understand when to consider a DOLs application process

Skills:

- To be able to explain a DOLS to a family member

- To know how to register a DOLS for a patient

Attitudes:

- To understand that DOLs are in existence for a reason to protect vulnerable patients

Definitions:

The Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards is the procedure prescribed in law when it is necessary to deprive of their liberty, a person who lacks capacity to consent to their care and treatment in order to keep them safe from harm.

Practical Definition:

Article 5 of the Human Rights Act states that “everyone has the right to liberty and security of person. No one shall be deprived of his or her liberty [unless] in accordance with a procedure prescribed in law”.

Sometimes thought when someone is not aware of what is happening you might need to provide them care or treatment that goes against this. DOLS is in place to ensure that this is monitored correctly.

Deprivation of liberty should only be used when unavoidable, and every effort should be made to prevent the need to deprive someone of their liberty. Equally, it must be used for the minimum amount of time possible.

Social Care Institute for Excellence

Key Points from Discussion

What is a deprivation of liberty safeguard (DOLs)?

- The Deprivation of liberty Safeguards are an amendment to the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA), which apply in England and Wales, which came into force in April 2009.

Bournewood Case

- The safeguards were introduced in 2005, because the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) decided in the Bournewood case that our legal system did not give adequate protection, to people who lacked mental capacity to consent to care or treatment and who needed limits put on their liberty to keep them safe from harm. Since then case law has provided more nuance to the process.

- The case concerned Mr L, a 49- year-old man with autism, who, lacked capacity. He had lived in Bournewood Hospital from the age of 13 for over thirty years. In 1994 he was discharged into the community to live in an adult foster placement with carers Mr and Mrs ‘E’.

- 3 years later on 22 July 1997 Mr L became agitated at a day centre he attended and was admitted to the Accident and Emergency Department at Bournewood Hospital under sedation. Due to the sedative, HL was compliant and did not resist admission, so doctors chose not to admit him using powers of detention under the Mental Health Act.

- HL never attempted to leave the hospital, but his carers were prevented from visiting him in order to prevent him leaving with them

- For about three months in 1997, Mr L was an in-patient at Bournewood Hospital. He was not detained under the Mental Health Act 1983 (‘MHA 1983’); rather, he was accommodated in his own ‘best interests’ under the common law doctrine of ‘necessity’.

- Mr L brought legal proceedings against the managers of the hospital, claiming that he had been unlawfully detained.

- The High Court rejected the claim. It held that he had not been detained, and that any detention would have been in his best interests and so lawful.

- Court of Appeal disagreed. It took the view that Mr L had been detained, and that such detention would only have been lawful under MHA 1983.

- The House of Lords reversed this decision – it agreed with the High Court.

- The ECtHR has agreed with the Court of Appeal. It found that Mr L was detained, so that the ‘right to liberty’ in Article 5 of the ECHR would be engaged.

- Further, it held that detention under the common law was incompatible with Article 5 because it was too arbitrary and lacked sufficient safeguards (such as those available to patients detained under MHA 1983).

The Small Places blog: good summary of DOLS and this case

There is no specific definition of deprivation of liberty in the Mental Capacity Act 2005, but decisions must adhere to the ECHR who state that a deprivation of liberty has three elements:

- An objective element of confinement in a restricted space for a non- negligible period of time

- A subjective element that the person has not validly consented to that confinement

- The detention being attributable to the state

When does “normal care” become a “deprivation of liberty” is not always clear.

The MCA Codes of Practice states:

The difference between deprivation of liberty and restriction upon liberty is one of degree or intensity. It may therefore be helpful to envisage a scale, which moves from ‘restraint’ or ‘restriction’ to ‘deprivation of liberty’.

Is it a deprivation or just a restriction of liberty?

The MCA allows restrictions and restraint to be used but only if they are in the best interests of a person, who lacks capacity to make the decision themselves. In addition the restrictions and restraint must be proportionate to the harm the care giver is seeking to prevent.

It may be difficult to tell whether a restriction on liberty is actually a deprivation of liberty requiring authorisation, within the wide range of circumstances that may occur. The Law Society provides some guidance to assist professionals decide whether a DOLs application is required as it can be hard to decide.

It has a list of examples of the type of restrictions on liberty found in care homes/hospitals or private dwellings and includes:

- keypad entry system

- assistive technology such as sensors or surveillance

- observation and monitoring

- expecting all residents to spend most of their days in the same way and in the same place

- care plan saying someone can only go into the community with an escort

- restricted opportunities for access to fresh air and activities (including as a result of staff shortages)

- set times for access to refreshment or activities

- limited choice of meals and where to eat them (including restrictions on residents’ ability to go out for meals)

- set times for visits

- use of restraint in the event of objections or resistance to personal care

- mechanical restraints such as lap-straps on wheelchairs

- restricted ability to form or express intimate relationships

- assessments of risk not based on the specific individual; for example, assuming all elderly residents are at a high risk of falls, leading to restrictions in their access to the community.

- Case in 201: Three weeks in ICU for woman with a learning disability was not a deprivation of liberty but rather a restriction of movement: ‘In my judgment, any deprivation of liberty resulting from the administration of life-saving treatment to a person falls within this category.’

The courts have identified certain pointers, which suggest that someone is more likely to be deprived of their liberty, rather than just restricted when:

- A person who want to leave is being stopped from doing so, either by staff or a locked door, for more than a few hours;

- A person is being given medication as a sedative to stop them leaving;

- The staff of the home or hospital take control of a persons life so that they decide if and when they can have visitors, speak on the phone, go out of the building and so on, which impacts on their ability to maintain social contacts.

- A decision has been taken by the hospital/care home that the person will not be released into the care of others, or permitted to live elsewhere, unless they consider it appropriate

- A request by carers for a person to be discharged to their care is refused

- The person loses autonomy because they are under continuous supervision and control

Reducing the risk of depriving someone of their liberty

- Involve structured decision making for every patient, with regular review and the reasons for each decision documented clearly

- Follow principles of good care planning

- Make a formal assessment of capacity

- Before admitting someone to a hospital/care home warranting deprivation of liberty, consider if less restrictive means could have the same outcome

- Ensure contact is maintained between the patient and carers, friends and relatives, providing advocates for each through services, possibly independent, if required.

- Review plans regularly.

MCA (Mental Capacity Act)

As with any assessment, which involves working with a person where there are concerns about their capacity it is imperative that we remember the basic principles of the MCA (check out episode 1.6) and we ensure that every effort is made to support, a person to make their own decisions, before beginning a best interests assessment.

As a reminder therefore, the starting point of any assessment must be the 5 core principles of the MCA:

- An assumption of capacity unless it is established that the person lacks capacity

- Not to treated a person as unable to make a decision unless all practicable steps to help them to do so have been taken without success.

- A person is not to be treated as unable to make a decision merely because they make an unwise decision.

- An act done, or decision made, under the MCA for or on behalf of a person who lacks capacity must be done, or made, in their best interests.

- Before the act is done, or the decision is made, regard must be had to whether the purpose for which it is needed can be as effectively achieved in a way that is less restrictive of the person’s rights and freedom of action.

Not everyone who lacks capacity requires a DOLS and this must be assessed on a person by person basis – will any care provided be restrictive?

When can someone be deprived of their liberty?

This is the case when:

- The person lacks the capacity to consent to the arrangements made for their care or treatment (consideration will need to be given to an assessment of capacity and a best interest meeting and who is best placed to undertake these);

- The arrangements amounting to a Deprivation of Liberty are in the person’s best interest to protect them from harm;

- The arrangements are proportionate response to the likelihood and seriousness of harm;

- There is no less restrictive alternative;

- An authorisation is recommended by the Best Interests Assessor following the DOLs assessment process;

- For Domestic settings a DOLs authorisation could be recommended by a social worker on behalf of the local authority if applying to the court of protection for a Domestic DOLs authorisation.

The ‘acid test’

In March 2014, the Supreme Court issued a judgment in relation to a deprivation of liberty, in the cases of P v Cheshire West and Chester Council and another and P and Q v Surrey County Council, which clarified what may constitute a situation whereby someone can legally have their liberty taken away, it became widely known as ‘the acid test’.

This involves asking two key questions:

1. is the person free to leave?

This is not about whether the person expresses a wish to leave but about what the home/hospital would do if the person tried to leave.

2. is the person subject to continuous supervision and control?

In addition it is important to consider whether:

a) The person can consent to the level of supervision and control; and

b) Whether the placement is ‘imputable’ to the state i.e. the state is held responsible

In addition the judgement identified that in all cases, the following are not relevant to the application of the test:

- the person’s compliance or lack of objection;

- the relative normality of the placement, which means the person should not be compared with anyone else; and

- the reason or purpose behind a particular placement

How is deprivation of liberty authorised under a DOLs?

If the home or hospital (the Managing Authority) thinks it needs to deprive someone of their liberty they have to ask for this to be authorised by the Local Authority where the person ordinarily resides (the Supervisory Body). This can be requested up to 28 days in advance of when they plan to deprive the person of their liberty.

The managing authority will complete a form requesting a standard authorisation, which is sent to the supervisory body, who has 21 days to decide whether the person can be deprived of their liberty. In an emergency situation the managing authority can grant themselves an urgent authorisation for 7 days, which can be extended for a further 7 days only.

What are the assessments and who does them?

At least two trained professionals are involved in the assessment:

- The “Best Interest Assessor” (BIA)

This is most often a qualified social worker, but it could be a nurse, occupational therapist or psychologist. This person undertakes an assessment to decide if the individual is being deprived of their liberty. They can also advise on how to reduce the restrictions on the person and how long the authorisation should be for. The BIA is appointed by the Supervisory Body.

- The “Mental Health Assessor”

This will be a doctor, usually a psychiatrist, geriatrician or general practitioner with experience in dealing with mental disorders. They will have had extra training in the DOLs process.

The Mental Health Assessor decides if the person is suffering from a “mental disorder” or not. This covers a range of conditions, but includes dementia, long-term effects of brain injury and a learning disability.

The assessment needs to determine whether the conditions are met to allow the person to be deprived of their liberty under the safeguards, which is determined by using the following six assessments:

Six assessments:

- An age assessment: to make sure that the person is aged 18 or over.

- A mental health assessment:to confirm that the person has been diagnosed with

a ‘mental disorder’ within the meaning of the Mental Health Act.

- A mental capacity assessment:to see whether the person has capacity to decide upon their care and support needs and accommodation.

- A best interests assessment:to see whether the person is, or is going to be,

deprived of their liberty and whether it is in their best interests.

This should take account of the individual’s:

- values and any views they have expressed in the present or the past, and

- The views of their friends, family, informal carers, anyone who expresses an interest in the person and any professionals involved in their care.

- An eligibility assessment:to confirm that the individual is not detained under the Mental Health Act 1983 or subject to a requirement that would conflict with the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards. This includes being required to live somewhere else under Mental Health Act guardianship or community treatment order.

If it is thought that the individual needs care or treatment for their mental disorder in hospital, then the Mental Health Act has to be used and DOLs no longer applies.

- A ‘no refusals’ assessment:to make sure that the deprivation of liberty does not conflict with any advance decision the person has made, or the decision of an attorney under a lasting power of attorney for health and welfare or a deputy appointed by the Court of Protection.

If any of the conditions are not met, a deprivation of liberty cannot be authorised.

If a standard authorisation is authorised it cannot be for longer that 12 months.

The authorisation must:

- Be In writing

- Include the purpose of depriving the person of their liberty

- State why the Supervisory body considers the person to meet the legal conditions for using a DOLs.

- Contain any conditions attached to the authorisation i.e. steps to maintain contacts or meet cultural needs.

Conditions to the DOLs authorisation set by the BIA (Best Interests Assessment):

The DOLs COP paragraphs 4.74.and 4.75 states:

The best interests assessor may recommend that conditions should be attached to the authorisation. For example they may make recommendations around:

- contact issues, issues relevant to the person’s culture or other major issues related to the deprivation of liberty, which – if not dealt with – would mean that the deprivation of liberty would cease to be in the person’s best interests.

But it is not the best interests assessor’s role to specify conditions that do not directly relate to the issue of deprivation of liberty

In recommending conditions, best interests assessors should aim to:

- impose the minimum necessary constraints: so that

- they do not unnecessarily prevent or inhibit the staff of the hospital or care home from responding appropriately to the person’s needs

Relevant Person Representative (RPR):

A relevant person’s representative must be appointed as soon as possible this can be either:

- a family member or friend who agrees to take this role.

- Or if there is no one willing or able to take this role on an unpaid basis, the SB must pay someone, such as an advocate, to do this.

The person and their representative can request the authorisation to be reviewed at any time, to see whether:

- the criteria to deprive the person of their liberty are still met, and

- if so whether any conditions need to change.

The person and their relevant person’s representative have a right to challenge the deprivation of liberty in the Court of Protection at any time.

If the person has an unpaid relevant person’s representative, both they and their representative are entitled to the support of an IMCA. It is good practice for supervisory bodies to arrange for an IMCA to explain their role directly to both when a new authorisation has been granted.

The Managing Authority has a duty to do all it can reasonably do to explain to a detained person and their family what their rights of appeal are and give support.

If the RPR cannot continue in their role for any reason a new RPR must be appointed.

The case of AJ v Local Authority [2015] EWCOP 5 gives guidance about the role of the RPR, IMCAs and the local authority in ensuring that a person lacking capacity is able to challenge their deprivation of liberty. A relative appointed as an RPR did not communicate the resident’s views about not wishing to be placed in residential care as they disagreed with them.

The judgment found the local authority should have appointed an alternative professional RPR because they knew about this disagreement.

Deprivation of liberty in domestic settings

In Cheshire West, the Court confirmed a deprivation of liberty can occur in domestic settings, if the State is responsible for imposing the arrangements.

This includes a placement in a supported living arrangement in the community.

Where there may be a deprivation of liberty in such placements, it must be authorised by the Court of Protection.

In Staffordshire County Council v SRK & Another [2016] EWCOP 27, this principle is restated. The court decided that a 24 hour privately funded and arranged care package for someone lacking mental capacity in their own home came under the deprivation of liberty protections, as it was sufficiently attributable to the state.

What happens if authorisation is refused?

If any of the criteria for the six assessments are not met, the supervisory body must refuse an authorisation request.

The managing authority must ensure then ensure that the person’s care is arranged in a way that does not amount to a deprivation of your liberty.

The supervisory body, or a relative, or anyone else who is commissioning the care, has a responsibility to purchase a less restrictive care package to prevent deprivation of liberty.

If the BIA does not agree to the DOLS paragraphs 4.72 and 4.73 of the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards Code of Practice states:

The best interests assessor must provide a report that explains their conclusion and their reasons for it. If they do not support deprivation of liberty, then their report should aim to be as useful as possible to the commissioners and providers of care in deciding on future action (for example, recommending an alternative approach to treatment or care in which deprivation of liberty could be avoided). It may be helpful for the best interests assessor to discuss the possibility of any such alternatives with the providers of care during the assessment process

The right to advocacy

If there is no appropriate family or friend who can support the person during the assessment procedure for a DoLS authorisation, an Independent Mental Capacity Advocate (IMCA) must be appointed by the SB. It is the responsibility of the MA to inform the SB, that support is required at the time of the request for the assessment.

An IMCA is an independent person with relevant experience and training who can make submissions to the people carrying out the assessments and, if necessary, challenge decisions on their behalf. Their role is to find out information about the persons for example their beliefs, values and previous behaviour, to help assess what is in their best interests.

Taking a case to the Court of Protection

The Court of Protection was created by the Mental Capacity Act 2005 to oversee actions taken under the Act, including those relating to DOLs, and to resolve any disputes involving mental capacity.

A case is usually only taken to the Court of Protection if it has not been possible to resolve the matter with the MA and SB, either by asking for an assessment to be carried out or a review of an existing authorisation. This may be in form of a formal complaint.

The following people can bring a case to the Court of Protection:

- the person who is being deprived of liberty, or at risk of deprivation

- an attorney under a Lasting Power of Attorney

- a Court of Protection appointed deputy

- a person named in an existing Court Order related to the application

The Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice

Provides an explanation of the Act and the obligations of those, including health professionals, caring for people who lack capacity.

Curriculum Mapping:

This episode covers the following areas (n.b not all areas are covered in detail in this single episode):

| Curriculum | Area | |

| Higher Specialist Training Geriatric Medicine | 3.2.7 Ethical and Legal Issues

17 .Principles of Medical Ethics and Confidentiality | |

| NHS Knowledge Skills Framework | Suitable to support staff at the following levels:

| |

| Foundation curriculum | Section

1.2 1.3 1 | Title

Delivers patient centred care and maintains trust Behaves in accordance with ethical and legal requirements Mental capacity |

| Core Medical Training | Principles of medical ethics and confidentiality

Legal framework for practice | |

| GPVTS program | 2.01 The GP Consultation in Practice: Apply the law relating to making decisions for people who lack capacity to the particular context of an individual patient

3.05 Care of Older Adults: Core Competence: Maintaining an ethical approach 3.10 Care of People with Mental Health Problems | |

| ANP (Draws from KSF) | Section 25 Legislation KSF HWB2 Level 4 |