4.02 Parkinson’s Disease

Presented by:

Dr Iain Wilkinson (Consultant Geriatrician East Surrey Hospital)

Dr Jo Preston (Consultant Geriatrician St George’s Hospital)

Additional voices from: Dr Joseph Withersgreen and Dr Marie Smith

Broadcast Date: 29th August 2017

CPD log

Click here to log your CPD online and receive a copy by email.

Tweetchat #MDTeaClub

Social Media spots this week

When to suspect, assess, and appropriately manage patients with hypoactive #delirium. Includes @will_s_t infographic https://t.co/7zpDOf5SVs pic.twitter.com/fOdkEP9vA6

— The BMJ (@bmj_latest) May 29, 2017

Shared by @edubru:

Variations in vital signs in the last days of life in patients with advanced cancer

J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014 Oct;48(4):510-7.

Show notes

PDF here

Learning Outcomes

Knowledge:

- To be able to recognise the common presentation of Parkinson’s disease

- To understand when to refer a patient for further assessment of a potential movement disorder

- To understand why it is important to deliver medications on time – every time for a patient with Parkinson’s disease

- To see that a patient with Parkinson’s disease may need assistance from a range of members of the MDT

Skills:

- To be able to simply explain the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease to a patient and their relatives

Attitudes:

- To understand that Parkinson’s disease has motor and non-motor symptoms

- To understand that for a patient the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease may be a life changing event

Firstly – we are going to talk about idiopathic Parkinson’s disease – we are not going to talk about other forms of parkinsonism or the so called Parkinson plus syndromes.

We are going to focus on how it may present to you as an MDT member and some of the key things to think about – we are not really going to talk much about drugs or drug treatments…

We are planning a mini-series to explore in more detail the broad topic of PD.

Definitions

- Probable best done chronologically – and will take most of the episode!

- First described by James Parkinson in his Essay on the shaking palsy in 1817

“Involuntary tremulous motion, with lessened muscular power, in parts not in action and even when supported; with a propensity to bend the trunk forward, and to pass from a walking to a running pace: the senses and intellects being uninjured.”

- In the mid-1800s, Jean-Martin Charcot was influential in refining and expanding this early description and in disseminating information internationally about Parkinson’s disease. Also that there seemed to be ‘typical’ and ‘atypical’ cases. Importantly he noted bradykinesia as a key cardinal feature.

“Long before rigidity actually develops, patients have significant difficulty performing ordinary activities: this problem relates to another cause. In some of the various patients I showed you, you can easily recognize how difficult it is for them to do things even though rigidity or tremor is not the limiting feature. Instead, even a cursory exam demonstrates that their problem relates more to slowness in execution of movement rather than to real weakness. In spite of tremor, a patient is still able to do most things, but he performs them with remarkable slowness. Between the thought and the action there is a considerable time lapse. One would think neural activity can only be effected after remarkable effort.”

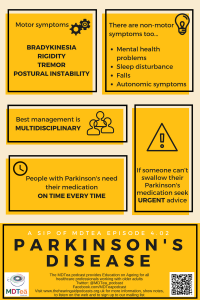

Motor symptoms

- These are the most common means of presentation for people with PD

- May present to a number of members of the MDT

- The two most commonly noted problems are: slowness of movement (difficulty walking) and tremor.

- Referrals therefore can come from a number of places – e.g. doctors, PT’s, OTs, SaLT etc.

NICE guidelines says: PD should be suspected in people presenting with tremor, stiffness, slowness, balance problems and/or gait disorders.

NICE Guidelines – Parkinson’s disease in over 20s: Diagnosis and management

For the actual diagnosis of Parkinson’s Disease working through the brain bank criteria I think gives a good practical thought process for making a diagnosis.

Step 1 is to diagnose a parkinsonian syndrome:

- Bradykinesia (this is a must – and is slowness of movement)

- At least one of the following :

- Muscular rigidity (so increased tone)

- 4-6 Hz rest tremor (most common in the hands and like rolling pills)

- Postural instability not caused by primary visual, vestibular, cerebellar, or proprioceptive dysfunction

Step 2 is to exclude other conditions:

This is quite a specialist thing really and at this point you should refer your patient – untreated to a specialist clinic.

Step 3 is supportive things to the diagnosis:

Usually 3 or more of the following:

- Unilateral onset

- Rest tremor present

- Progressive disorder

- Persistent asymmetry affecting side of onset most

- Excellent response (70-100%) to levodopa

- Severe levodopa-induced chorea

- Levodopa response for 5 years or more

- Clinical course of ten years or more

Once the diagnosis has been made the natural history of the disease is that it will progress:

The order / manner of progression is described by Hoehn and Yar:

| Stage | Median Time to Transit (Months) | |

| 1 | Unilateral involvement only usually with minimal or no functional disability | – |

| 2 | Bilateral or midline involvement without impairment of balance | 20

62 (stage 2.5) |

| 3 | Bilateral disease: mild to moderate disability with impaired postural reflexes; physically independent | 25 |

| 4 | Severely disabling disease; still able to walk or stand unassisted | 24 |

| 5 | Confinement to bed or wheelchair unless aided | 26 |

Hoehn M, Yahr M (1967). “Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality.”. Neurology. 17 (5): 427–42

Progression through the stages is variable – based on a study of 695 patients with PD. (Cox regression analysis revealed that older age-at-diagnosis, longer PD duration, and higher Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) motor scores at baseline were associated with a significantly faster progression through various H&Y stages).

Or, more simply… Diagnostic phase > Maintenance phase > Complex phase > Palliative phase

Basal Ganglia

The basal ganglia normally exert a constant inhibitory influence on a wide range of motor systems – stopping movement at inappropriate times – it’s complicated(!)

When a decision by the higher brain centers is made to perform a particular action, the inhibition is reduced for the required motor system, thereby allowing movement to happen.

Dopamine acts a the neurotransmitter to facilitate this release of inhibition, so high levels of dopamine function tend to promote motor activity, while low levels of dopamine function, such as occur in PD, demand greater exertions of effort for any given movement. In PD there is an accumulation of alpha synuclein which leads to cell death (particularly in the basal ganglia and substantia nigra). Thus, the net effect of dopamine depletion is to produce hypokinesia, an overall reduction in motor output – e.g when walking.

Now the treatments therefore all provide more dopamine in one way or another. So when a patient has the drugs they can move around better – as the drugs wear off they can’t. The drugs work by and largely dose to dose – so when it wears off it is not working at all – so the timing of drugs is really important.

The patient / relatives will know when they take their treatment – its best not to fiddle with these timing and work towards the patient and not your / out system. If they needs drugs at 06:45, or 08:50 or 13:15 then find a way to give them then – don’t just stick to the drug round times.

If they can’t swallow don’t just do nothing – ask for advice urgently from someone that can give it (e.g doctor / pharmacist / PD nurse etc).

Non-Motor Symptoms

However it’s not all just about the movement… there are non movement symptoms too! An appreciation of these has occurred over the last 30 years.

Non-Motor symptoms relate to changes elsewhere in the brain / dopaminergic system. There are lots of these but the key areas to think about are:

1) Mental health problems

- Depression and

- Psychotic symptoms

- Typical antipsychotic drugs (such as phenothiazines and butyrophenones) should not be used in people with PD because they exacerbate the motor features of the condition.

- Dementia

2) Sleep disturbance (we might do a whole episode on this in series 5… let us know if you want one!)

- Restless legs syndrome (RLS) and

- Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behaviour disorder in people with PD and sleep disturbance.

- Sudden onset of sleep should be advised not to drive and to consider any occupational hazards. Attempts should be made to adjust their medication to reduce its occurrence.

- Daytime hypersomnolence

- Nocturnal akinesia

3) Falls – numerous reasons for this

4) Autonomic disturbance

People with PD should be treated appropriately for the following autonomic disturbances[9]:

- urinary dysfunction

- weight loss

- dysphagia

- constipation

- erectile dysfunction

- orthostatic hypotension

- excessive sweating

- sialorrhoea.

So who needs to be involved in looking after people with PD?

In line with many other complex diseases which need a MDT approach. Alongside the medical team there is:

Specialist nurse interventions

People with PD should have regular access to the following:

- clinical monitoring and medication adjustment

- a continuing point of contact for support, including home visits, when appropriate

- a reliable source of information about clinical and social matters of concern to people with PD and their carers

- which may be provided by a Parkinson’s disease nurse specialist.

Physiotherapy

Physiotherapy should be available for people with PD. Particular consideration should be given to:

- gait re-education, improvement of balance and flexibility

- enhancement of aerobic capacity

- improvement of movement initiation

- improvement of functional independence, including mobility and activities of daily living

- provision of advice regarding safety in the home environment

The Alexander Technique may be offered to benefit people with PD by helping them to make lifestyle adjustments that affect both the physical nature of the condition and the person’s attitudes to having PD.

Occupational therapy

Occupational therapy should be available for people with PD. Particular consideration should be given to:

- maintenance of work and family roles, home care and leisure activities

- improvement and maintenance of transfers and mobility

- improvement of personal self-care activities, such as eating, drinking, washing and dressing

- environmental issues to improve safety and motor function

- cognitive assessment and appropriate intervention.

Speech and language therapy

Speech and language therapy should be available for people with PD. Particular consideration should be given to:

- improvement of vocal loudness and pitch range, including speech therapy programmes such as Lee Silverman Voice Treatment (LSVT)

- teaching strategies to optimise speech intelligibility

- ensuring an effective means of communication is maintained throughout the course of the disease, including use of assistive technologies

- review and management to support safety and efficiency of swallowing and to minimise the risk of aspiration.

Social Work

Patients with PD should be assessed under the principles of the care act – and are entitled to appropriate support from social care services.

The charity sector (in particular Parkinson’s UK) are very helpful in this regard and the PD UK website has a wealth of information on the area.

The findings indicate how maximising quality in social care delivery for people with Parkinson’s disease can impact on health and well-being. Long-term or short-term benefits may result in prevented events and reductions in health and social care resource. Health professionals can be instrumental in early detection of and signposting to social care.

So in conclusions…. Our practical Definition:

“The recognition of the non-motor symptoms over the last 30 years has led to somewhat of a change in the way of thinking about PD. The common taught idea now is that PD is a neuropsychiatric condition with motor complications and needs a multi-professional management approach.”

Curriculum Mapping:

This episode covers the following areas (n.b not all areas are covered in detail in this single episode):

| Curriculum | Area | |

| NHS Knowledge Skills Framework | Suitable to support staff at the following levels:

| |

| Foundation curriculum (2016) | Section

10 13 | Title

Recognises, assesses and manages patients with long term conditions.

Prescribes safely |

| Core Medical Training | The patient as central focus of care

Involuntary Movements Geriatric Medicine (Movement Disorders) Neurology (Movement Disorders) | |

| GPVTS program | Section 2.03 The GP in the Wider Professional Environment

Section 3.05 – Managing older adults

Section 3.18 – Neurological problems

| |

| ANP (Draws from KSF) | Section 7 – Parkinsonism

| |

| PA Matrix of conditions | Parkinson’s Disease – Category 1B | |

| Higher specialist training – Geriatric medicine | 3.2.2 Immobility – including locomotor disorders and Parkinson’s disease

39 Movement Disorders |