9.05 – Poverty in Older Age

Presented by: Iain Wilkinson, Jo Preston, Alice O’Connor

Faculty: Jackie Lelkes

Broadcast Date: 31st March 2020

Social Media

Learning Outcomes

Knowledge

- Understand definitions of poverty in the UK

- Understand factors contributing towards poverty in older age

- Enhance understanding of the impact of poverty on older people

Skills

- Develop knowledge and understanding of poverty for older people

Attitudes

- Appreciate that poverty is not always related to income or material possessions.

CPD Log

Show Notes

Definitions

Formal definition

According to Age UK (2019) the most commonly used definition of poverty is someone who lives in a household with an income below 60% of the current median (or typical) household income, taking into account the number of people living in the household.

According to this definition, Age UK identified that:

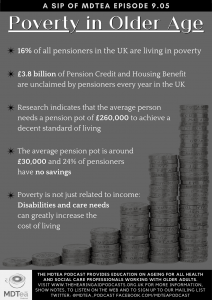

- 16% of all pensioners (or 2 million people) are living in poverty

- Over half of these (9% of all pensioners) are living in “severe poverty” (incomes of less than 50% median)

- 11% of all pensioners are living “just above the poverty line”, with incomes between 60 and 70% of median.

Some other helpful definitions

Relative poverty:

One approach is to look at the resources people have and compare them to what everyone else has (these are known as “relative measures”). The people at the bottom end are considered to be in poverty in comparison to everyone else.

Absolute poverty:

Another approach is to define a fixed set of resources, perhaps by defining a set of essentials people need to have in order to have a decent standard of living (known as “absolute measures”). Anyone who can’t afford that standard is considered to be in poverty, regardless of what everyone else has.

https://fullfact.org/economy/poverty-uk-guide-facts-and-figures/

Main Discussion

As of 2017/18 the number of pensioners living in poverty in the UK was growing.

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation describes pensioner poverty as being “wide, but not deep”, i.e. many older people fall below the poverty line but are not in severe poverty.

Age UK (2019) identify that some groups of older people are more at risk of living in poverty than others:

- private tenants (35%)

- older people living in the social rented sector (29%)

- older people who own their home outright (13%) – not quite sure how this one works: perhaps holding onto a home they can no longer afford in order to pass it on to children?

- Ethnic minority pensioners: Asian or Asian British (31%), black or black British pensioners (32%) – compared with white pensioners (15%)

- Older pensioners: those aged 80 and over (19-20%) compared to 15% of 65-69 year olds

- 15% of women compared to 18% of men

- 23% of single women compared to 20% of single men, compared to 13% of couples.

It is important to be aware that financial difficulties are about more than income. For example, people may incur higher costs if they have a disability or care needs, or may need to spend more on heating if they live in a cold, poorly insulated home.

Disability and poverty

- Disability brings additional living costs, which can be very large – sometimes hundreds of pounds a week. These can include care costs, additional transport costs and home adaptations e.g. a stairlift.

- The benefits system does give additional allowances for disability (mainly the attendance allowance for older people – the system is changing to Personal Independent Payment [PIP] but this needs to be claimed before the age of 65). However the JRF argue that if the benefits system fails to make any allowance for the higher living costs that disability brings, then disabled people appear to be better off than they actually are.

- In terms of providing support to older people with a disability in the UK, we have a dual system of public support. Central government pays disability benefits, whilst local authorities manage the provision of social care services. Two quite separate systems with little overlap.

- According to the JRF report this dual system is quite good at using limited resources to minimise the number of older disabled people in poverty. But it is much less effective in protecting people from severe poverty. This particularly applies to people with a high level of disability who may not know how to negotiate the benefits system.

Joseph Rowntree Federation. 2017. Disability and Poverty in Later life.

Available at: https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/disability-and-poverty-later-life

Fuel Poverty

Concerns over the welfare of older people in winter have led to interventions and advice campaigns meant to improve their ability to keep warm, but older people themselves are not always willing to follow these recommendations.

In this paper the authors drew on an in-depth study that followed twenty one older person households in the UK over a cold winter, and examined various aspects of their routine “warmth-related practices” at home (and the rationales underpinning them).

They found that, although certain aspects of ageing did lead participants to feel they had changing warmth needs, their practices were also shaped by the problematic task of negotiating identities in the context of a wider stigmatisation of older age and an evident resistance to ageist discourses. After outlining the various ways in which this was manifest, they conclude by drawing out the implications for future policy and research.

Other ways to look at poverty include:

- Material deprivation: which is measured by asking if people lack certain goods and services (link to material deprivation index below)

- Minimum income standards: which considers the cost of goods and services required by different households, which contributes to an acceptable standard of living (used extensively by Joseph Rowntree Foundation)

https://www.jrf.org.uk/income-benefits/minimum-income-standards

- Self-reported measures – people are asked how well off they consider themselves.

Material Deprivation Rate:

As defined by EU-SILC, the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions

The indicator measures the percentage of the population that cannot afford at least three of the following nine items:

- to pay their rent, mortgage or utility bills;

- to keep their home adequately warm;

- to face unexpected expenses;

- to eat meat or proteins regularly;

- to go on holiday;

- a television set;

- a washing machine;

- a car;

- a telephone.

Severe material deprivation rate is defined as the enforced inability to pay for at least four of the above-mentioned items.

Persistent material deprivation rate is defined as the enforced inability to pay for at least three (material deprivation) or four (severe material deprivation) of the above-mentioned items in the current year and at least two out of the preceding three years. Its calculation requires a longitudinal instrument, through which the individuals are followed over four years.

https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Glossary:Material_deprivation

NERD ALERT

The findings of The Institute for Fiscal Studies (2019) give a mixed, and almost contradictory, picture:

- During the recession of 2007-08, pensioners did much better than working-age families.

- Since then, pensioner incomes have, on average, grown substantially more than non-pensioner incomes.

- Official data show a rise in relative pensioner poverty since 2011, whilst absolute pensioner poverty has stagnated (having fallen almost continuously in preceding decades). However, this may be to do with data quality issues:

- Income growth has slowed down among low-income pensioners, due to an apparent decline in private pension incomes.

- This may reflect the fact that those who choose to draw their entire defined contribution pensions as a lump sum are not recorded as having private pensions in the survey data.

- However, it does not fully explain the income decline, as the overall number of older people with private pension incomes has also fallen.

- A slowdown in income growth from employment may also contribute.

- However, the state pension has been made more generous, offsetting the changes due to reduced employment income growth.

Additionally:

- Pensioners’ housing costs have continued to rise, reflecting a sustained rise in private and social rents.

- Rates of material deprivation among pensioners have actually been falling: that is, the number of pensioners unable to afford items in the material deprivation index.

Institute for Fiscal Studies. 2019. Living standards, poverty and inequality in the UK: 2019

Coping mechanisms:

The Age UK report found that older people find a number of coping mechanisms to help them with living on a low income, including:

- maximising income through claiming benefits, (link to benefits below)

- staying in work ,

- cutting down,

- doing without wherever possible,

- turning down social invitations due to cost, and

- adopting a mind-set of ‘making do’.

Age UK (2019) Poverty in Later Life. https://www.ageuk.org.uk/globalassets/age-uk/documents/reports-and-publications/reports-and-briefings/money-matters/poverty_in_later_life_briefing_2019.pdf

Benefits:

The latest estimates show around £3.8 billion of Pension Credit and Housing Benefit alone are unclaimed by pensioners every year in Great Britain

This may be for a number of reasons, including being unaware that they are eligible, not knowing how to claim, or feeling ashamed.

Whilst Nationally nearly a quarter (24%) of pensioners have no savings, research from Royal London (insurance company) indicates that the average person needs a pension pot of £260,000 to achieve a decent standard of living, which rises to £445,000 if the person is paying rent.

However the average pension pot is around the £30,000 mark.

Social security schemes:

Sjoberg (2014) discussed how social security schemes can help to reduce poverty risk and increase resources available for individuals and families.

This article analyses the link between life expectancy and effective coverage of old-age pension schemes, in a sample of 93 high- and middle-income countries.

The analyses support the idea that social security schemes may have positive effects on population health

This article also demonstrates that there is no evident relationship between levels of economic development and social security legislation

and

that there is no clear cross-national relationship between levels of economic development and the proportion of the population covered by old-age pension schemes.

Sjoberg, O. 2014. Old-age pensions and population health: a global and cross-national perspective

Austerity in the UK:

There has been significant concern that austerity measures have negatively impacted health in the UK.

A longitudinal study of 324 local authorities in 2016 examined whether budgetary reductions in Pension Credit and social care have been associated with recent rises in mortality rates among pensioners aged 85 years and over.

The research found that between 2007 and 2013:,

- Each 1% decline in Pension Credit spending (support for low income pensioners) was associated with an increase of 0.68% in old-age mortality per beneficiary.

- Each reduction in the number of beneficiaries per 1000 pensioners was associated with a mortality increase of 0.20%

- Similar patterns were seen in both men and women.

So essentially they concluded that rising mortality rates among pensioners aged 85 and over were indeed linked to reduced spending on social care and income support for poorer pensioners.

According to the Joseph Rowntree Foundation there is a real challenge to end the iniquity of poverty premiums, which is where people in poverty pay more for the same goods and services. For example,

- the use of pre-payment meters for gas and electricity, which costs more.

- individuals in poverty are less likely to switch their energy supplier to get a better deal.

- In some industries, i.e. utility companies, bills often carry additional costs arising from public policy or investments in new infrastructure. JRK argue that “there is a strong case for firms to design, in conjunction with government, fairer ways of sharing these additional policy costs”

Social Isolation:

A report by the JRK in 2017 identifies that social isolation is more frequent amongst pensioners than working-age adults.

14% of all pensioners say they have no or only one close friend compared with 8% of working-age adults.

They also found that the link between social isolation and income appears to be stronger among pensioners than working-age adults.

- One in seven (14%) pensioners in the poorest fifth of the population identified that they had no or only one close friend,

- Compared with only one in twenty (5%) of those in the richest fifth.

Joseph Rowntree Foundation. 2016. Can we solve poverty in the UK?https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/we-can-solve-poverty-uk

Joseph Rowntree Foundation. 2017. Impact of Poverty on relationships. https://www.jrf.org.uk/data/impact-poverty-relationships

Curriculum Mapping

NHS Knowledge Skills Framework

- Core 1 Level 3

- Core 2 Level 1

- Core 6 Level 2

- HWB1 Level 1

- HWB2 Level 2

- HWB3 Level 1

- HWB4 Level 1

Foundation Programme

- Sec 1:3 Vulnerable groups

- Sec 1:4 Self directed learning

- Sec 3:16 – employment, poverty, socioeconomic health inequality

GPVTS

- 3.05 Making decisions – influence of social situation on disease processes

- 3.05 Clinical management – support services

- 3.05 Maintaining performance, learning and teaching

- 3.05 Community orientation

Core Medical Training

- Managing long term conditions and promoting patient self-care – Health and social service provision

- Health promotion and public health – Factors affecting health

- Management and NHS structure – Debates impacting on service provision

Internal Medicine Stage 1

- Generic CIPs – Category 1:2

- Safeguarding

- Generic CIPs – Category 4:5

- Epidemiology & global health

- Public health and health promotion

- Social deprivation

Geriatric Medicine Specialty Training

- Managing long term conditions and promoting patient self-care – Health and social service provision

- Health promotion and public health – Factors affecting health, Determinants of worldwide health

- Management and NHS structure – Debates impacting on service provision

- 27. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment

- Factors influencing health status in older people

- Measures employed in measuring health status and outcome

- Have knowledge of the major sources of financial support

- Have knowledge of the range of agencies that can provide care and support

- 29. Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Disease and Disability

- Influence of poverty on access to healthcare and health outcomes