10.6 Older Prisoners Health

Presented by: Iain Wilkinson, Jo Preston, Sophie Norman

Special Guests: Warren Stewart

Broadcast date: 25/05/2021

Social Media

Learning Outcomes

Knowledge

- To be aware of the unique problems and issues that face older prisoners in prison and on release

- To be aware that the number of older prisoners is growing, and with this, there is an associated increase in demand for health and social care from this unique group of individuals

Skills

- To know which organisations are available to provide support to older prisoners, and be able to signpost patients to these as needed

Attitudes

- To understand that discourses and practices are often loaded in favour of security and efficiency over care and support

CPD Log

Show Notes

Definitions

There is no official universal age threshold used to define an ‘older prisoner’. But…

- Age UK defines older prisoners as those aged over 50, a younger age than we would usually say describes an ‘older person’ in the community.

- The age of 50 has also been adopted by HM Prison and Probations service to categorise ‘older prisoners’

Some estimates suggest many older people in prison have a physical health status of about ten years older than their contemporaries in the community

The Ministry of Justice points out that there is actually wide variety in the rate of ‘ageing’ amongst prisoners. Factors like age at time of incarceration contribute to this disparity, and the MOJ suggests that using chronological age as a way to guide the correct management of an individual should be replaced instead by an assessment of need.

House of Commons Justice Committee. Ageing prison population, Report 2019-2021

Older prisoners (England and Wales) Policy position paper, Age UK

Main Discussion

Who are the people we are talking about? And Why are we looking at this topic?

Who

- We are talking mainly about men in this episode – in the UK the prison population is roughly 70,000 men, and <4000 are women

- 17% of the prison population is aged 50 and older

Why?

- The proportion of older prisoners is projected to grow from 13,616 in June 2018 to 14,100 by 2022 in England and Wales

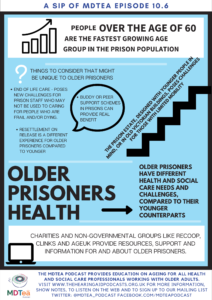

- People aged 60 and over are the fastest growing age group in the prison population.

- From 2002 – 2014 there was an increase of 146% in prisoners classified as older prisoners.

- Most older people in prison are serving long sentences

- Older prisoners may have more complex needs than younger prisoners

Our objectives, RECOOP. Accessed 25/05/2021

Prison Population Projections 2018 to 2023, England and Wales. Ministry of Justice, 2018

Why are the numbers of older prisoners increasing?

- Recent increases in number of convictions made overall in the justice system for sexual offences, including historic sexual offences (see: ‘Operation Ore’)

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-20237564

- There are 4 ‘types’ of older prisoner, as suggested by the Prison Reform Trust:

Those for whom it is their…..

- First time in prison, serving along sentence

- First time in prison, serving a short sentence

- Those in prison for repeat offences, with recurring experiences of custody

- Those serving long-term or indeterminate sentences, who have grown older inside prison

Growing Old in Prison. Prison Reform Trust, 2003

- There were 5,294 prisoners under immediate custodial sentence for sexual offences in 2002; by June 2019, it had risen to 13,196.

- People convicted of this type of offence are disproportionately older, compared to those convicted of other offences.

- 45% men >50 are serving sentences for sexual offences

- 80% of men >8o are serving sentences for sexual offences

(this is compared to 18% of whole prison population)

(NB – there are much more mixed profiles for older women prisoners, with only 4% serving sentences for sexual offences)

- Sentence inflation

- >3x as many people were sentenced to 10 years or more in the 12 months to June 2019 than in the same period in 2007

- Average sentence lengths for sexual offences have increased in particular – given the high proportion of older prisoners convicted for sexual offences, this may have had a strong effect on the ageing of the prison population.

Prison: the facts. Prison Reform Trust, Bromley Briefings Summer 2019

Who is responsible for older prisoners?

Policy, commissioning and funding healthcare for offenders differs in England and Wales and between custody and community.

- ENGLAND

- The responsibility for commissioning healthcare services for inmates (incl drug and alcohol support services, but excluding OOH and emergency) rests with NHS England.

- Offenders in the community are expected to access the same services as the rest of the local populations and responsibility lies with CCGs.

- Local authorities are responsible for commissioning public health services (eg drug and alcohol services).

- WALES

- Local Health Boards (LHBs) commission healthcare services in public sector prisons (including clinical drug treatment services), and are responsible for commissioning mainstream healthcare services which offenders in the community will access.

The Care act 2014; declared social care and prisons must work together to assess needs of individuals, and social services are to provide required support/assistance if an individual is deemed over the threshold of need. In a survey by the Prison Trust in 2010 93% of respondents made no mention of social care involvement in their Prison.

Healthcare for those in prison should be provided to the exact same standard as would be expected for any other citizen living in the community in the UK.

Further to that, the RCGP document “equivalence of care in secure environments in the UK” clarifies that equivalence of care does not necessarily mean the same care – care should be consistent in terms of range/accessibility/quality, but needs of the prison population will vary from those in the community, and approach to delivery in secure environments may be different.

Healthcare for offenders. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/healthcare-for-offenders accessed 25/05/2021

Equivalence of Care in Secure Environments in the UK. RCGP Position Paper July 2018

Good practice with older people in prison – the views of prison staff. Prison Reform Trust 2010

Care Act 2014 on Legislation.Gov.UK

What are the specific needs of/challenges facing older prisoners?

A 2013 Inquiry by the Justice Select Committee found that in too many cases older prisoners were being held in establishmentswhere their basic needs were not being met, and were being released back into the community without adequate support.

Key problems highlighted included

- Rising numbers of older prisoners

- Unique resettlement needs of older prisoners

- Accessibility of the prison estate

- Difficulties in accessing health and social care services.

Older prisoners (England and Wales) Policy position paper, Age UK

Facilities + the prison estate

- ~⅓ prison buildings are Victorian, designed without any emphasis on accessibility for non-able bodied people living within them

- Even some more modern buildings (according to G4s) do not provide step free access to key facilities (communal areas, washing facilities, exercise and health care areas)

- Issues may be related to the design of cells/blocks even if they are accessible/prisoners are mobile;

- eg . even simple things like the lack of a toilet in a cell; a prisoner may have trouble at night time, needing to request permission to go to the toilet or wait in a queue – a problem disproportionately affecting older prisoners as a need for access to night time sanitation is more likely.

From a report by HMIPS; ‘Who cares? The lived experience of older prisoners in scotland’s prisons’:

“I’m seventy two and on the top bunk. I’m a lot fitter than my co-pilot, that’s why I’m up there.. I am a bit worried that I could fall and hurt myself when I’m trying to get in and out of my bed.”

The size of a prison might present issues for older prisoners if they have limited mobility or other impairments affecting things like participation in exercise, social or group activities

“It’s a bit embarrassing but half the time I wouldn’t go anywhere because I need to make sure I can get access to the toilet. When I need to go I need to go there and then, it’s embarrassing.”

What solutions might exist?

Alternative accommodation?

Peter Clarke, HM Chief Inspector of Prisons when talking about the future when it comes to housing older prisoners, or prisoners requiring care ; “….it would be a care facility with a wall around it, where there is sufficient security to hold those people safely, securely and decently……”

Separate accommodation?

In the same report by HMIPS as mentioned above, prisoners were asked whether they would rather be in a mixed age group environment or separated with other older prisoners. The general response was that they would rather remain in a mixed environment, though some had reservations and general consensus is that opinions are divided..

“No I quite like some of the young guys. You get a bit of banter with them and it kind of keeps you going a bit.”

“I’d prefer to be with a mix of people but some of the younger guys you know to stay away from. If I did get any hassle I’d hit them with my stick.”

House of Commons Justice Committee. Ageing prison population, Report 2019-2021

Social care

The Care Act 2014 set out requirements for local authorities and prisons to work together to respond to the social care needs of prisoners.

- Local authorities are responsible for the assessment of all adults who are in custody in their area, and who appear to be in need of care and support or have been referred for assessment – regardless of which area the individual came from or where they will be released to.

- Prisons and/or health services are required to inform local authorities when they feel someone in their care should be assessed re their care/support needs.

- …but anyone can make the referral – those in prison, families etc – on behalf of the older person

As with healthcare, prisoners are entitled to the same social care as the rest of the population – with the exception of being able to choose where they reside and receiving money directly in order to support their needs.

If a person is found to have care/support needs, a care and support plan must be drawn up, with the input of the individual for whom it is for – and if this is not possible/appropriate for any reason an advocate/independent advocate/LPA must be sought.

Unfortunately, in a 2020 publication from the Justice select committee, it was stated that while the care act 2014 brought some improvements, the standards of social care provision across the estate are patchy and concluded a more strategic and coordinated approach to deliver care is required

There are some examples of peer or buddy support in prisons as a response to a shortage of social care or to address needs of prisoners that fall below the eligibility criteria set out in the care act.

This is the case in both Devon and in the North West, where RECOOP, (a charitable organisation) supports prisoners who are 50+. Younger prisoners act as buddies, and following completion of a training programme provide non intimate support and promote independence.

Dying well in custody

Older prisoners account for over 50% of all prisoners that die in custody – making this a key topic in the discussion of older prisoners’ health and care.

J Shaw et al, in a 2020 briefing paper ‘Avoidable natural deaths in prison custody: putting things right’ (from the RCN and the independent advisory panel) reports that there were a total of 165 ‘natural’ deaths in custody in 2019, with a general upward trend from 2009 (100), and a high in 2017 (189)

The paper states the most common cause of natural death in custody was cardiovascular disease, followed by malignancy, and the average age of someone dying in custody was 56 years old (compared to 81 in the community).

A Prisons and Probation Ombudsman annual report 2018-19:

- A number of prisons have built specialist palliative care cells/units for prisoners with specialist requirements

- Some prisons have developed links with local hospices to improve care.

However, they state that these measures/interventions are by no means universal on the prison estate

Issues highlighted by the PPO (Prisons and Probation Ombudsman) on multiple occasions include;

- Early release: to be considered as soon as possible after a terminal diagnosis is made. (This is different from release on temporary licence, and is usually not considered until death is within three months), which can take time to process..

- In a 2013 PPO report, 78 of 214 people were considered for compassionate release, of whom 13 were granted it. Delays to early release decisions meant that of the 78 who were under consideration, 26 died while awaiting a decision.

The dying well in custody charter (2018) – from the Ambitions for Palliative and End of Life Care Partnership:

- Recognises that compassionate release – though the ideal – may not be achievable for all prisoners who are living with terminal illness.

- Acknowledges that providing EOLC in a prison is complex and very different to doing the same in a clinical setting.

The charter centres around the ideas that care should be individualised, timely, and involving and supporting the physical and emotional needs of the individual and all those close to them (other prisoners, family, friends and prison staff).

They introduces standards which include;

- Keeping an EOL register to ensure patients’ needs are recognised and care is delivered appropriately

- The appointment of a dedicated family liaison officer to support visitation and coordinate care

- Access for families of prisoners at the end of life and access to care and clinical advice 24/7.

The charter recognises :

- that staff may not have been involved in or see themselves in a caring role

- May not have looked after people at the end of their life in the past

- It also recognises that prisoners who have been in custody for a long time may feel comfortable with the staff around them, who have been a consistent presence and support, and their peers in the prison may be friends and support and this may impact choices re care.

Dying Well in Custody Charter Dying Well in Custody Charter. From the Ambitions for Palliative and End of Life Care Partnership, 2018.

Example of good practice:

In a document promoting the adoption of the Gold standard Framework for recognition and care for those in the last year of life, HMP Norwich was identified as the first prison to become accredited under the framework (2016).

Detention of terminally ill patients in restraints when outside of prison for medical treatment, was strongly criticised in the PPO bulletin mentioned above, and leads us on to discussing restraint in the context of healthcare.

Restraint

From the PPO in 2015:

Prisoners often remained in restraints after their condition seriously declined. The actual risk the prisoner presented at the time was rarely considered….a terminally ill prisoner should never need to die in restraints, nor do i think any escorting officer should have to go through the trauma of being chained to a prisoner as he or she dies….with an ageing population, visits to hospitals and hospices will only increase, and with them daily test of the humanity of our prison system. .”

Nigel Newcomen, PPO, Perrie Lecture 2015

Restraint when seeking medical help/treatment

The PPO states that as of 2018/19, unfortunately, there remain many cases where very elderly/frail/unwell patients are escorted to hospital in handcuffs, at times remaining in restraints until shortly before death.

- The high court rules that use of restraints when receiving medical treatment/care should be necessary and proportionate

- Their stance is that disproportionate use of restraints is inhumane and unacceptable

- They call for prison leadership to reflect on why some establishments are able to address the issue successfully and some not.

Prison officers often accompany prisoners when they are patients, and there may be little awareness that there is no legal requirement for them to be present during consultations. As a healthcare professional – if you see fit, and only if it is safe and appropriate – you can ask them to leave while you assess patients who are in custody

The health of older prisoners

The physical and mental health problems of all prisoners (and particularly older ones) is a complex and big topic all of its own, and not covered extensively here.

It is worth noting though, as for those working outside the prison sector, it is still likely that there will be contact with people from custody settings

- There is a high mental and physical health burden in the older prisoner cohort

- Up to 90% of prisoners aged 50 or over have at least one moderate or severe health condition, and over 50% have three or more (ie multimorbidity).

- Among prisoners aged 60 or over, rates of ‘major illness’ may be as high as 85%

- According to the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy, around 5% of prisoners aged 55 or over are estimated to be affected by dementia, though other estimates vary.

- More than half of all elderly prisoners present with a mental illness.

House of Commons Justice Committee. Ageing prison population, Report 2019-2021

We mentioned ‘natural’ deaths in custody when talking about the 2020 report from the RCN and IAP. The report is clear to state that ‘natural death’ does not always mean ‘unavoidable death’ and coroners/investigations have stated that in some cases, deaths could have been prevented.

Areas identified in the paper as needing improvement in order to address the health of the older prison population and reduce avoidable deaths include:

- More comprehensive primary care pathways

- Better communication between services (including when in police custody/in the court system) and on discharge from prison

- Immediate access to community medication

- Addressing the issue of missed outpatient appointments

- This is often with no follow up from hospitals to find out why an appointment was missed/to encourage future attendance

- Looking at prison staff shortages, meaning staff escort may not always be possible is important

- Older prisoners with chronic conditions are more likely to miss appointments compared to younger prisoners with more typically acute problems who will be prioritised if resources are limited

- A fear of bullying might prevent appointment attendance

- In 2017-2018 4 in 10 prisoner appts were missed/cancelled, at a cost of £2million to the NHS

Recommendations made in the paper to improve things included

- Use of telemedicine where appropriate (to improve appointment attendance)

- Secondary care clinics in prisons in major specialities

Release and resettlement

Older prisoners may require more/different support on release compared to younger prisoners.

Sobering and important to note that In the first two weeks following release, mortality rates are 12 times higher than for the general population.

Strategic direction for health services in the justice system: 2016-2020. NHS England 2016

- Older prisoners may be less familiar with new technologies/systems that are needed for access to benefits/employment/social activities

- A higher proportion of older inmates are serving terms for sexual offences, and licence conditions due to the nature of this offence may mean approved premises in which to live are harder to find.

- Approved premises may not have facilities required by people with sensory impairments, restricted mobility etc (things which affect older prisoners more than younger)

Both of these issues may mean staying in prison until end of a sentence despite eligibility for parole, or being released to no fixed abode at the end of a sentence.

- Perhaps due to serving longer sentences older prisoners will have…

- Maintained fewer contacts/relationships outside prison over their time in custody

- No physical home to return to

- Higher levels of institutionalisation (contributing to higher levels of social isolation and associated issues on release)

Older prisoners (England and Wales) Policy position paper, Age UK

An article in ageing and society 2014 interviewed older prisoners before and after release in the north of england:

- Pre release planning was perceived among the cohort to be non existent

- There was a perceived lack of formal communication and continuity of care reported, causing anxiety to the prisoners.

- Despite high levels of anxiety about living in probation approved premises on release, those who did live in them had their immediate health and social care needs met to a better standard than those who didn’t

The charity ‘Restore Support Network’ provides one-to-one peer support for older prisoners prior to release and for people with prior convictions in the community if they are over 50 and have health and/or social care needs. They echo a sentiment common to issues raised in this episode that delivery of health/social care services where needed on release from prison is patchy and dependent on where in the country someone is released to/from.

https://www.restoresupportnetwork.org.uk/

Issues with continuity of care on release

- Release may happen before registration with a new GP has occurred

- There may be issues with access to/lack of ID being a barrier to accessing GP care

- Access to prescription medications and communication between prison health services/GPs on release is an area of difficulty in some cases

- Links to ongoing social care may be disrupted

Older prisoners (England and Wales) Policy position paper, Age UK

Other topics to consider which we have not covered, and links to further information;

- Dementia

The prisons project, from the alzheimers society

:https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/blog/prison-project-raising-awareness-dementia-prisons

From the Prisons and probation ombudsman:

- Exercise, nutrition and other determinants of health relevant to older adults living in the prison environment are important, and something we did not have time to cover in the episode. Included in these determinants is social isolation.

Loneliness and isolation has been identified as an issue affecting older prisoners.

- Some older prisoners over the retirement age may not be engaged in employment within prison

- Loss of independence in activities of daily living may lead to marginalisation and isolation from other prisoners dissociating themselves from an older prisoner

- Frailty or physical/sensory impairment might limit someone’s ability to be involved in organised activities in the prison, or limit access to communal areas

- Not being able to ‘shout the loudest’ might mean older prisoners are neglected when there are pressures on prison staff

Good practice:

HMP Norwich Library service – for prisoners with cognitive impairment and dementia, where prisoners and staff meet weekly to talk about their week.

RECOOP – provide day centres which give prisoners the opportunity to socialise and participate in meaningful activity.

Curriculum Mapping

NHS Knowledge Skills Framework

- Health safety and security

- Level 1

GPVTS

- Professional topic guides

- equality diversity and inclusion

- Being a general practitioner

- Working well in organisations and systems of care

- Managing complex and long term care

- Caring for the whole person and the wider community

- Flexibility and interdependency with curricula of other specialties and professions

Internal Medicine Stage 1

- Geriatric medicine

- Deterioration in mobility

- Palliative medicine and end of life care

- Psychosocial concerns

Geriatric Medicine Specialty Training

- Clinical CiP 4: managing patients in an outpatient clinic, ambulatory or community setting