5.05 BPSD – Management

Episode 5.05 – BPSD Management

Presented by: Dr Jo Preston, Dr Iain Wilkinson, Dr Victoria Osman-Hicks, Dr Cate Bailey, Chris O’Connor

Broadcast Date: 3rd April 2018

Click here for a pdf of the sip of MDTea poster

Click here for a pdf of show notes

CPD log

Click here to log your CPD online and receive a copy by email.

Tweetchat #MDTeaClub

We will be hosting a ‘journal club’ type tweet chat to discuss topics raised in this episode using #MDTeaClub

Join us to discuss topics raised in the episode and spread any resources you may have!

Social Media this week

Iain’s Choice – Five Top Tips to Prevent Pressure Ulcers from NHSI

Jo’s Choice – Rainy Days and Mondays – a family who use the rules of improv comedy to improve communication in cognitive impairment in This American Life Podcast 532 – Magic Words, Act 2

Main Show Notes

Learning Outcomes

Knowledge:

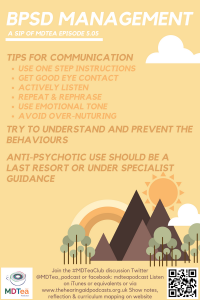

- To describe the non-pharmacological and pharmacological management options for BPSD

Skills:

- To feel more confident engaging with people suffering with cognitive impairment to de-escalate situations.

- To know when to use which medication and when not to.

Attitudes:

- Engage families and carers in conversation about why these behaviours could be happening

- To consider behaviours that might challenge as an unmet need rather than a challenge per se.

Definitions:

“Dementia is a syndrome – usually of a chronic or progressive nature – in which there is deterioration in cognitive function (i.e. the ability to process thought) beyond what might be expected from normal ageing. It affects memory, thinking, orientation, comprehension, calculation, learning capacity, language and judgement. Consciousness is not affected. The impairment in cognitive function is commonly accompanied, and occasionally preceded, by deterioration in emotional control, social behaviour or motivation.”

Key Points from Discussion

When a person living with dementia starts to experience different or exaggerated behaviours, that would not have been usual for them, it can have a significant impact not just the person with dementia but also their family or carers.

Many of the behaviours which are called “behavioural” symptoms of dementia are not actually symptoms of dementia itself, but are other symptoms/problems which cannot be communicated because of the impact of dementia on language and communication. Together this is called “Behavioural and Psychological Symptoms” or BPSD in Dementia.

We have talked about this previously and used the PIECES is a framework to help to guide our approach

Physical problem or discomfort

Intellectual or cognitive changes

Emotional

Capacities (previous habits etc.)

Environment

Social and cultural

Case Study

Mrs Harman 80+ year old lady admitted to Acute Medical Unit from here care home. She has become increasingly agitated and the care home “could not manage her”. The main reason for admission was an apparent increased level of confusion, agitation and for an assessment if there was a possible infection, She is refusing to give a urine sample but staff notice strong smelling urine when she had used the toilet also had been incontinent of small amount of urine. She is refusing to wear a pad and has angrily reacted when asked to use one – Telling them all to go away.

History from family over last 6 months

Mrs Harman’s family report she has had a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s for 5 years and has been in a care home for the last 6 months as she was no longer able to manage at home with a three times a day care package.

In the last 6 months at the care home she is reportedly repetitive, disorientated to where she is and increasingly apathetic, not allowing staff to wash and dress her. This is a significant change from her pre-morbid personality; she was always very proud of her appearance and well dressed as a schoolteacher.

She reports that no one has been to see her all week and that her family do not care. She does not retain her family visiting after a few minutes, Some family members have tried to reason with her but this has led to arguments .

In the last few months she is seeming increasingly suspicious and making accusations of others stealing things. She now refuses to let a son in law in to her room and is convinced her grandchildren are stealing from her.

She was started on Donepezil at diagnosis about 5 years and continues to take it but the staff find it difficult to get her to eat, drink, wash, dress and engage in activities. Her family are concerned the home are not managing her needs.

ON AMU

Mrs Harman is reporting she is wanting to leave to go home. She believes she is in a bus station and wants to get the next bus home to get her Husband’s supper ready as he will be home soon from work. (We know from family that her husband dies 5 years ago)

In attempt to calm Mrs Harman A staff member asked her to wait in the chair by the desk and that a bus will be a long soon. This pacified her for a short while but after 5 minutes was wanting to leave saying that people are lying to her.

She tells another staff member that she needs to get home to her husband the staff member looks at her notes and informs her that the her husband is not the down as the next of kin and there is no record of him. Another staff member tells her that her husband passed away a few years ago. Mrs Harman becomes very upset about this and refuses to believe this getting angry and then crying.

Effective communication takes practice and may feel uncomfortable at first. It is important to remember that when validating Mrs Harman’s feelings, you should not feed into the confusion by making statements such as “I saw your husband a few minutes ago” or I’ll help you find your husband.” Using validation believes that the confused patient may be able to realise that she is confused and by taking part in his confusion, the staff member undermines the patient’s trust.

Link to good article on “therapeutic lying”

Validation Therapy

Validation therapy is a method of communication developed by social worker Naomi Feil.

- It uses empathy to help people regain dignity, reduce anxiety, and prevent withdrawal.

- The problem of using reality orientation, trying to reorient this patient to person, place, and time will most likely be unsuccessful because she is unable to remember current information.

- It is very likely that this method of communicating with her will result in her becoming increasingly agitated.

- If she does not remember that her husband has died, this may upset her.

- By using validation therapy, the staff member validates the patient’s need to see her husband and explores the reason she is concerned about him.

- This method is kinder and will usually result in Mrs Harman communicating her needs to the staff member. Naomi Feil describes validation as exquisite listening or listening with empathy.

Tipsheet for interacting with people with dementia who are anxious or distressed.

- There is also a recent systematic review which demonstrates that communication training is beneficial.

Communication skills training in dementia care: a systematic review of effectiveness, training content, and didactic methods in different care settings. Eggenberger, E., Heimerl, K., & Bennett, M. I. (2013). International Psychogeriatrics, 25(3), 345-358.

Practical tips aspect of caring for Mrs Harman

What can staff do to manage Mrs Harman on the unit?

Firstly step back and look at the situation through her eyes

- A busy noisy environments

- People asking her different questions people she does not know or recognise

- Is the name of the hospital or the ward anywhere to be seen (does the initials AMU mean anything?).

- What do the staff know about Hrs Harman. Is there any way they have of connecting with her. Past times work Discuss the types of techniques the staff can use.

- Is there an orientation board?

- Are staff roles and uniforms clear?

The use of the “This is Me”, “Reach out to me”, hospital passport or other patient personal information forms helps staff to make a connection with the patient. Do they like talking about their job, football team, children etc. The passport also means that her close family can be with her for as much as the day as they can (rather than abiding by the hospital visiting hours).

This is Me from the Alzheimer’s Society

Managing the behaviour (prevention)

- Behaviour should be seen as a way of communication of unmet needs

- The patient may not cope with the stress around them in an unfamiliar environment .

- Unable to understand what is happening and respond appropriately, Mrs Harman may become distressed and may attempt to strike out in anger or fear of her current situation.

Unmet needs that Mrs Harman may have:

- Pain or discomfort

- Needing the toilet and not knowing where it is

- Anxiety and fear due to unfamiliar environment

- Eyesight or hearing problems (when were they last checked)

- Social isolation, being left alone in a side room

- Poor medication management

- Do the family understand the diagnosis, have they received any support or diagnosis support.

Consider what the environment set up is. Is it dementia friendly? Could you navigate it if you didn’t know where you were? NHS Improvement have some guidance on how to assess this for yourself locally.

Would the person be more orientated if they had a familiar person around? Many hospitals are now using carer’s passports thanks to ‘John’s campaign’ which aims to give carers the right to support the person they are caring for in hospital as they would at home, if they wish.

Sedation should only be considered as the absolute last resort once de-escalation, change of environment, staffing support and when other strategies have failed. It should be only used if the patient’s behaviour is such that is causing herself or others significant harm and not to “calm her down” to make it easier for staff. Sometimes it is utilised on a single occasion to facilitate treatment (which is in the person’s best interests), ie: to make it easier to take a blood test, or put an IV in.

Back to the case….

After a few days delirium is ruled out and the collateral is clear that this is a gradually progressive deterioration over the last 6-12 months. The care home, whilst willing to try things is not able to look after here currently with the behaviours and care needs she currently has.

She is assessed by the OPMH Consultant or geriatrician and a decision is taken to add memantine to her donepezil. Her kidney function shows an eGFR of >50 and her baseline blood pressure is normal She is started on Memantine titration, with 5mg at night for the first week and weekly increases of 5mg until she reaches the full dose of 20mg ON which is the usual maintenance dose. She lacks capacity to consent to the medication changes and her family agree as best interest decision to try this. After the first week, it is noticed she is sleeping a little better and less agitated in the day as result. The care home re-assess her and report they are happy to have her back at the care home with some support from the OPMH team in the community It is discussed with the care home it will take up to 4 weeks to take full effect.

The OPMH nurse practitioner sees at the care home after 2 weeks, She supports the staff in the care home to develop person-centred care plans for her behaviour, cognition, continence, nutrition and wider needs. The family help by contributing to these plans and complete a “This is me”,

In the community, the OT from the OA CMHT helps with a bath and shower assessment and identifies that Mrs Harman prefers a strip wash to being under the shower. It is noted that she often accepts personal care from one particular female member of staff, with whom she has good rapport. Whenever possible this member of staff is rostered to work with Mrs Harman. The member of staff also shares with other staff Mrs Harman’s preferences and contributes to the development of the care plan, for when she is not able to be there. One way the staff identify to support Mrs Harman’s personhood is to lay out two options for clothes to put on after the bathing on the bed and let her choose one, as she has always been someone who enjoyed picking her outfit for the day. This process also provides visual prompts that the next activity will be to get dressed. The OT also looks at what Mrs Harman might still be able to participate in, from the list of available activities at the care home and finds that she prefers small groups, still enjoys music.

Music therapy has shown good evidence for reducing agitation and depression in dementia in care homes (though studies are of heterogeneous methodologies and types of therapies ranging from individual to group, to music played during mealtimes)

Systematic review of systematic reviews of non-pharmacological interventions to treat behavioural disturbances in older patients with dementia. Abraha et. al BMJ 2017

The care home team, with their activity co-ordinator, develop some small activities to engage her. engaging her despite her struggling to attend the larger groups sessions. She has a personalised weekly activity programme with visits from the PAT dog (as she always likes dogs), dusting her table (as she was always house proud) and singing with the in-house church service as she always liked to attend).

He discusses distraction techniques to try when she starts to become more agitated and encourages the use of ABC charts to get further details of her behaviours.

The OPMH nurse completes fortnightly Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Index scores with the staff and they notice over the coming months an improvement in behaviours that challenge despite her progressive dementia.

The GP meets with her family and the care home staff and they agree an anticipatory care plan, make decisions about resuscitation and start to have conversations about preparing for end of life in the future and supporting them to understand about the progressive nature of dementia and helping them to plan how she wishes to be cared for in her final illness.

Pharmacological Approaches (medication)

Cholinesterase inhibitors

- Is the patient already on a Cholinesterase inhibitor?

> Cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil and Rivastigmine) reduce the progression of Alzheimer’s and Lewy-Body dementias, delay the need for a care home and can help delay and reduce BPSD symptoms,

Memantine

- For BPSD in Alzheimer’s Dementia, there is good evidence for Memantine (an NMDA receptor blocker) This is available as a tablet and an oral pump and is titrated up against renal function usually over 4 weeks usually in weekly steps.

> It can reduce agitation and aggression

> It can help sleep (it is sedating) so often given at night or in a split dose

> It may help mood symptoms (apathy, low mood, irritability)

>It can help cognitive symptoms (cognitive enhancer)

Efficacy of memantine on behavioural and psychological symptoms related to dementia: a systematic meta-analysis. Maidment et. al Annals of Pharmacotherapy 2008

Treatment effects between monotherapy of donepezil versus combination with memantine for Alzheimer’s Disease: A meta-analysis. Chen et al. PloS 2017

Antidepressants

- In moderate dementia, one trial shows watchful waiting for 12 weeks is as good as SSRI and Mirtazapine did not help the patient per se but helped the carers (i.e. the benefits of a sedating drug at night). This trial significantly changed clinical practice and less antidepressants are now used or used for a trial with a review date.

- It is important clinically to differentiate between apathy and depression. Memantine is beneficial in apathy. But also, explaining to families and carers that apathy can be a part of the progression of the disease and which may help them to feel less disappointed if someone seems less interested in things than they used to.

Trazadone, a sedating antidepressant is sometimes used in divided low doses often for its sedating effect in clinical practice. Although it has limited trial evidence for its use and often may be used when more evidence based treatments have failed.

Other drugs

> very limited evidence for anti-convulsants/mood stabilisers and these are often poorly tolerated in older people

> Sleep medications may help in some patients such as Z-drugs (Zopiclone)., but are not used routinely and are associated with increased risk of falls. Melatonin showed some efficacy in improving sundowning and agitated behaviour in dementia. The evidence is inconclusive however as melatonin has a relatively benign side effect profile it is often worth a try (see recent episode on sleep!).

> Effective management of pain has been shown to improve agitation. Regular paracetamol is a safe option in patients with dementia and should be considered to help manage aches and pains. It is worth considering the patient’s previous medical history – have they got a diagnosis of OA, which is very likely to give them pain. Sometimes medications get missed between community and nursing home, or between nursing home and hospital and often a trial of regular analgesia is effective. Thorough observation of a particular act of care, eg: washing and dressing can uncover that there is pain on movement, and so giving analgesia prior to a wash might be helpful.

Efficacy of treating pain to reduce behavioural disturbances in residents of nursing homes with dementia: cluster randomised clinical trial. BMJ. Husebo et al, 2011

Inappropriate sexual behaviour can be a common problem. Pharmacological treatments for which there is low-level evidence of efficacy in the literature include antidepressants, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, cholinesterase inhibitors, hormonal agents, and beta-blockers. None of the drugs discussed here is licensed for use in ISB, and elderly people, particularly those with dementia, are at high risk of adverse effects.

Inappropriate sexual behavior Treatment

However, often non-pharmacological interventions can be effective following a thorough analysis of the behaviour itself (eg: male staff to wash and dress a disinhibited male patient).

Antipsychotics are only indicated as a last resort for severe and challenging behaviours, severe agitation and or psychosis (so called target symptoms) at low doses. Antipsychotic prescribing in dementia is monitored at a European level and should be only considered for the shortest period, at the lowest dose with significant others in agreement

> Risperidone is the only antipsychotic licenced for uses for up to 6 weeks. No others have licences and so are “off licence” and require prescribers to ensure additional monitoring. The usual starting dose is 0.25mg OD PO, increasing to 0.25mg BD if needed.

> Stroke risk should be considered and discussed with the patient or family (3 in 100), as well as increased falls risks and other risks outlined previously. There si also monitoring required (bloods, ECG, BMI, BP) at initiation and at each dose increase and then minimum annually in primary care),

- Benzodiazepines may be prescribed, usually on an as required basis.

- Short acting Lorazepam orally is preferred at 0.5mg starting dose (max 2mg/24hrs) at a minimum of 4 hour intervals, as half life about 4 hours..

- Additional nursing care may be required after prescription due to the sedating effect (increased falls risk).

- Some patients have a paradoxical reaction and become more agitated with benzodiazepines. In these patients, they are best avoided.

Good Nottingham guidelines for medication in BPSD

Mrs Harman with access to evidence based treatments using a bio=psycho-social approach and person-centred care plan is enabled to live at the care home without further moves.

Other members of the MDT who may be involved in her care include: Alzheimer’s society (for ongoing support for family), psychology (assistance with behavioural analysis in care home), social workers regarding packages of care, increasing care needs, community matrons, community palliative care, speech and language therapists (as dementia can often affect swallowing in the later stages), continence nurses

1 year later she passes away peacefully in her home, which is her preferred placed of death. The family thank for the team caring for her for making the last year of her life as high quality as it could be and ensuring she did not have further unnecessary hospital admissions. She enjoyed attending the church service, singing and was cared for with dignity in the privacy of her own room, close to her family who remained able to visit her regularly and keep her part of the family.

Curriculum Mapping:

This episode covers the following areas (n.b not all areas are covered in detail in this single episode):

| Curriculum | Area | |

| NHS Knowledge Skills Framework | Suitable to support staff at the following levels:

| |

| Foundation curriculum | Section

1.2 3.10 | Title

Delivers patient centred care and maintains trust Recognises assesses and manages patients with long term conditions |

| Core Medical Training | The patient as central focus of care

Confusion, Acute / Delirium Aggressive / Disturbed Behaviour Memory Loss (Progressive) | |

| PA matrix of conditions |

| |

| Higher Specialist Training in Geriatric Medicine | 3.2.2 Common Geriatric Problems (Syndromes)

33 Dementia 42. Psychiatry of Old Age 49. Dementia and Psychogeriatric Services | |

| Geriatric Medicine Training Curriculum | 33. Dementia

Optional Higher Grid: Dementia and Psychogeriatric Services |

1 Response

[…] S5E5 – Management of BPSD […]