8.09 Polymyalgia Rheumatica – the forgotten condition?

Presented by: Dr Jo Preston, Dr Iain Wilkinson, Dr Alice O’Connor, Anne O’Brien (Specialist rheumatology physiotherapist and senior lecturer, Keele University)

Faculty: S-J Ryan

Broadcast Date: 3rd December 2019

Social Media

Anne:

Learning Outcomes

Knowledge:

- Describe a typical care pathway for a patient with PMR

- Identify which health professionals are most appropriate to support and manage patients with PMR

Skills:

- To be able to identify the main symptoms to support a diagnosis of possible PMR / GCA

- Offer some initial patient education and symptom management advice

Attitudes:

- To appreciate and promote a positive outcome for most patients with PMR

- To promote and encourage self-management strategies for patients with PMR.

CPD Log

Show Notes

Introduction

Let’s start with a case:

Mrs Jones, aged 76

Mrs Jones lives alone in a house with stairs, having been widowed 6 years ago. Usually fully independent, she drives and helps out at the WRVS at the local hospital once a week. She has a dog “Bramble” who she walks twice a day for 15 mins each time.

HPC: Rapidly development of shoulder and hip girdle pain two years ago. Within days was unable to walk outside, climb stairs or get dressed easily. Initially diagnosed as OA, PMR was then confirmed a month after symptoms began. Associated feeling of overwhelming exhaustion.

She is very anxious to keep her independence and to keep walking Bramble.

PMH:

Intermittent chest pain – diagnosed with mild CAD 8 years ago.

Asthmatic since childhood – well controlled with inhalers.

OA > Total hip replacement 4 years ago – Right

DH:

Atorvastatin – 20 mg daily, Aspirin – 75mg daily, Omeprazole – 20 mg daily, Beclomethasone inhaler – one puff BD, and Salbutamol inhaler – PRN

Definitions

PMR and giant-cell arteritis (GCA) are closely related conditions that affect persons of middle age and older, and frequently occur together. Many authorities consider them to be different phases of the same disease.

Giant-cell arteritis is a chronic vasculitis of large and medium-sized vessels. Although it may be widespread, symptomatic vessel inflammation usually involves the cranial branches of the arteries originating from the aortic arch.

Polymyalgia Rheumatica (PMR) is one of the commonest autoimmune inflammatory disorders affecting older people, who are typically over the age of 70. Originally thought to be a form of gout 1, PMR was first proposed as a discrete condition in 19572. Whilst sometimes self-limiting and often successfully managed with oral glucocorticoid therapy, PMR is associated with Giant Cell Arteritis (GCA), which can lead to permanent blindness.

Main Discussion

Please note, the Vancouver style references are listed at the bottom of the show notes in the download version.

- Older people presenting with rapidly developing shoulder or hip girdle aches and stiffness with no small joint inflammation, may have Polymyalgia Rheumatica (PMR), one of the most common inflammatory conditions affecting people over the age of 70.

- It can be difficult to diagnose because the classic signs and symptoms mimic other musculoskeletal and rheumatological conditions 3.

- PMR can disrupt and significantly impact upon an individual’s day to day functioning and quality of life4, but it usually has a good prognosis, with most people not requiring medical management after five years.

Incidence/ Prevalence

- The lifetime reported risk of developing PMR is 2.4% for females and 1.7% for males16. PMR is more prevalent in women (affecting two to three times more women than men) and much more likely to be observed in older adults 6, 17

- Mean age of PMR onset is reported to be 73, but incidence might be increasing8

- The overall prevalence of PMR in a population over the age of 50 is thought to be around 0.1-1.0% 21, 22, 23

- Geography also appears to influence incidence; higher incidence being observed for people living in the northern hemisphere, increasing with northern latitudes residence9

Giant Cell Arteritis

- Association: 5-10% of patients with PMR are also diagnosed with GCA.

- A strong association appears to exist between GCA and PMR

- Whilst rare with an estimated incidence of 10 per 100,000 patient years GCA is the most common form of large/ medium vessel vasculitis. Undiagnosed, there are potential serious consequences including permanent sight loss.

- Classically senior (over 70) female patients present with new headaches, scalp tenderness or temporal pain, visual disturbance and jaw claudication (pain on chewing).

- Where GCA is suspected, peripheral pulses should be examined. Subsequent investigations may include: ultrasound imaging (particularly to evaluate inflammation in potentially “silent” anatomical areas such as the aorta43); a temporal artery biopsy, which if positive confirms a GCA diagnosis, and/ or referral for an ophthalmology opinion.

So… let’s go back to Mrs Jones

“How would you explain the diagnosis to her?”

The symptoms you have sound quite typical for PMR.

It is a well-recognised condition caused by inflammation.

It can cause both pains and tiredness.

We have treatment (steroids) which usually works quite quickly, particularly for the aches and pains.

We would like to do some more tests to confirm what we think is going on (blood tests) and have a look at medications in case any of these are contributing (i.e. statins)

Pathogenesis:

(NERD ALERT)

- Overall there is a lack of consensus on the pathogenesis of PMR:

- Histological studies confirm an inflammatory element, probably giving origin to the classic neck and pelvic aching symptoms. Inflammation is observed on MRI and ultrasound imaging8 as peri-articular synovitis (inflammation of the synovium around joints), bursitis and tenosynovitis11 or shoulder or hip effusions (increased amounts of synovial fluid)12.

- Synovitis has also been identified from histological scrutiny of shoulder biopsies where macrophages and CD4 T cells have been identified13. Some suggest the oedema within the synovial sheaths of tendons, rather than synovial hyperplasia (the production of more synovial cells) is the more likely origin of pain and stiffness symptoms in PMR14.The role of inflammatory mediators is also yet to be fully understood. Elevated interleukin (IL)-6 levels are seen in both PMR and GCA, and raised IL 1-1β is also observed in PMR patients15, both of which are thought to potentially explain some of the systemic features of the condition13.

Diagnosis

There is no gold standard diagnostic test for PMR. It is generally agreed, however, that diagnosis should only be proposed following history, a clinical examination and identifying elevated inflammatory markers; typically both the Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) and C-Reactive Protein (CRP) levels are raised in the blood30, 8.

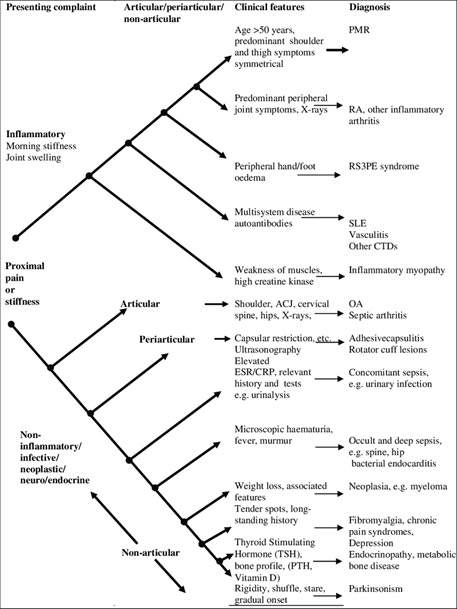

Good UK guidelines on the diagnosis of PMR exist This table / chart is from it…

Current guidelines for the management of PMR recommend that key pathologies should be excluded. (In particular, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), active infection or cancer 33.)

This appears to be particularly important in the first six months of presentation when incidence rate of new cancers is higher 34.

Investigations

Additional blood tests which should be negative in PMR, but can help to exclude other pathologies are8 :

- Rheumatoid factor – positive in RA

- Anticyclic Citrullinated Peptide (anti-CCP) – raised in RA

- Anti-nuclear antibodies – positive in systemic auto-immune conditions, e.g. SLE, infections or some cancers

- Creatinine phosphokinase (CPK) – raised in myositis or myopathy

- Alanine and aspartate transaminase (ALT and AST) – indicate liver pathology

Health professional assessments

- Most likely to meet older patients with PMR as a pre-existing comorbidity when consulting about other health issues.

- However a proportion of staff, working either in community practice settings or in rheumatology departments, may be the first to recognise the symptoms of undiagnosed (or recurring) PMR described by their patients.

- Assessments typically include some measurement of pain and stiffness, identified by both the patient and clinician in addition to inflammatory markers 58.

- Health professionals may identify the patient’s need for psychological support59. A sudden onset of seemingly vague symptoms may be very frightening, so listening to patient worries, educating and counselling, whilst also assessing for signs of anxiety or depression, may be very important 40. What are patients’ fears?

- Healthcare professionals should also be mindful of some of the hidden effects of taking steroids (such as loss of sleep), as well as the more visible steroid side effects i.e. the “moon face” (Cushing’s syndrome), striae of arms/ legs/ torso, and the kyphotic “buffalo hump” that may accompany secondary spinal osteoporosis. All of these side effects can cause additional distress for the patient with PMR, as can steroid-associated weight gain with resultant reduced activity and diminishing fitness levels.

- Establishing patient knowledge: A significant aspect of the assessment will include an evaluation of the patient’s knowledge and understanding of prescribed glucocorticoid medication and “red flag” monitoring signs. Does the patient understand what’s going on?

- Compliance with medication: The nurse or pharmacist is especially well placed to evaluate the patient’s likely compliance with medication55. Part of their assessment can therefore involve discussion about the patient’s past medical history (and concordance with medical management) as well as most recent health story, which should include how PMR symptoms are impacting upon daily life.

- Activities of daily living: General physical independence levels may be assessed and can be observed from the first encounter as a patient approaches a consultation room. This may include an overall evaluation of mobility, the support offered (+/- accepted) by accompanying family/ friend, as well as observation of how the individual sits down or removes clothing. If a physical examination is required (e.g. if personal hygiene may be a challenge), skin condition and any obvious muscle wasting can also be gauged. It may be at such a time that other features are observed (e.g. significant synovitis) in which case, the assessor may reflect on the diagnosis; might the patient be presenting as a PMR onset of RA, where pitting oedema of hands or feet and tenosynovitis may be features?32.

Symptom management/ relapse

- It is unusual to need additional medication to manage PMR symptoms. Giving clear messages to adopt good postures, avoiding any additional muscle or joint symptoms are important however.

- Whilst not evidence-based, some patients also anecdotally report using heat therapy (hot packs, warm showers or baths) to reduce shoulder and hip aches.

- Additionally promoting positive “keep moving” messages should not only reduce PMR-related stiffness, but can help prevent long-standing weakness and deconditioning quickly developed in less active older populations.

- A slow weaning of steroids is needed…

- Daily prednisolone 15 mg for 3 weeks > then 12.5 mg for 3 weeks > then 10 mg for 4–6 weeks > then reduction by 1 mg every 4–8 weeks or alternate day reductions (e.g. 10/7.5 mg alternate days, etc.)

- Sometimes ever slower weaning is needed, and some patients find it hard to ever stop treatment.

Patient education

Let’s go back to Mrs Jones…

What would you be saying to her as her specialist nurse?

Teaching patients to cope with PMR has been an identified nursing focus for some time (59). A key aspect of this will be empowering patients to be knowledgeable and confident enough to self-manage their condition. Identifying the bespoke needs of the patient will therefore be an important aspect of patient education. In addition to the steroid advice, other patient education will usually include:

- What is PMR; an explanation of the condition

- Explanation of the blood test results

- Minimising the impact of steroid side effects; encouraging mobility, promoting weight-bearing activity

- Monitoring skin condition, avoiding pressure or damage

- How to identify relapse in PMR; symptoms to note

- The risk of GCA; to pay attention to visual disturbances

- Recognising the signs of osteoporosis

- Health professional contact details for follow-up; helpline numbersAvailable patient support groups/ online fora, e.g. The PMRGCAuk charity

(http://www.pmrgca.co.uk/content/home-page)

- If available, offering ongoing support via a nurse-led telephone advice line can be very reassuring to patients, also serving to help triage and prioritise patients needing onward escalated medical management.

- Health professionals can also signpost patients to other online and telephone support. For example, in the UK the PMRGCAuk charity serves as a patient forum holding regular national and regional support group meetings, as well as raising awareness about both PMR/ GCA and promoting related research.

Patient priorities/ concerns

See the following article:

Overall prognosis – good news!

- Unlike so many other inflammatory/ rheumatic conditions, much better overall prognosis, but need to keep active whilst recovering!

- Whilst for many the overall prognosis for PMR is generally very good and doesn’t appear to affect mortality22, relapsing symptoms are remarkably common and thought to affect as many as 50% of patients 61, 62.

- Relapse has been defined by consensus as a “flare up of symptoms” illustrated by the patient reporting shoulder and/or hip pain (> 20mm on visual analogue scale) with a perception of shoulder pain exacerbated by activity and reduced elevation range of movement, together with an accompanying morning stiffness of more than 30 minutes. These indicators will often, although not always, be accompanied by abnormal CRP and ESR inflammatory markers. To minimise delay identifying possible relapse, the nurse may offer patients with PMR an urgent blood form to keep in reserve which facilitates prompt detection of rising ESR and CRP.

- Women, those who start on higher steroids dosages, or those who taper too fast are most likely to relapse63 but actual prediction of who will relapse remains difficult. When suspecting relapse, the nurse should always first consider other causes; for example a raised ESR associated with infection, before managing likely PMR relapse with an increasing steroid dosage64.

Key points from discussion

- Steroid management can give dramatic improvements within 72 hours, but most need to be kept on low doses at 2+ years (sometimes many years more)

- Pacing of activities very important as symptoms easily stirred up

- Balance rest vs. exercise

- Relapse is common – slow tapering of steroids essential, but very frustrating for patients

- Cardiovascular risk higher in PMR

Anne O’Brien’s references are listed in full in the downloadable show notes.

Further resources:

American College of Rheumatology PMR homepage: https://www.rheumatology.org/I-Am-A/Patient-Caregiver/Diseases-Conditions/Polymyalgia-Rheumatica

Versus Arthritis website:

Patient information about PMR: https://www.versusarthritis.org/about-arthritis/conditions/polymyalgia-rheumatica-pmr/

Steroid tablets information booklet: https://www.versusarthritis.org/media/1362/steroid-tablets-information-booklet.pdf

Steroid drug treatment information: https://www.versusarthritis.org/about-arthritis/treatments/drugs/steroids/

Curriculum Mapping

This episode covers the following areas (NB: not all areas are covered in detail in this single episode)

NHS Knowledge Skills Framework

- Core 2 Level 1

- Core 5 Level 1

- HWB1 Level 2

- HWB2 Level 2

- HWB4 Level 3

- HWB6 Level 2

- HWB8 Level 1

Foundation curriculum

- Sec 1:4 Self directed learning

- Sec 3:10 Long term conditions in unwell pt

- Sec 3:10 Support for pts

- Sec 3:13 Discussion of medication

Core Medical Training

- Managing long term conditions and promoting patient self-care – Rehabilitation and MDT, quality of life, patient self-care

- Top presentations: Headache

- Other important presentations: Immobility

- Geriatric medicine: MDT assessment, Rehabilitation targets, Deterioration in mobility, Osteoporosis

GPVTS program (within Care of Older Adults)

- 3.05 Data gathering and interpretation

- 3.05 Clinical management – referral pathways, prescribing hazards, iatrogenic disease

- 3.05 Managing medical complexity – Understand how co-morbidity will influence the management of existing disease and delay the early recognition of adverse clinical patterns

- 3.05 Practising holistically and promoting health

Geriatric Medicine Training Curriculum

- Managing long term conditions and promoting patient self-care – Rehabilitation and MDT, Quality of life, Patient self-care

- 28. Diagnosis and Management of Acute Illness: The non-specific acute presentations seen in older patients. Drugs, including compliance, interactions and unwanted effects, in older people.

- 29. Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Disease and Disability

- 30. Rehabilitation and Multidisciplinary Team Working: Physical therapies which improve muscle strength and function, Therapeutic techniques/training to improve balance and gait, Aids and appliances which reduce disability.

- 36. Poor Mobility

Find Us!

To listen to this episode head to our website, itunes or stitcher.

Give us feedback by emailing us, via twitter or facebook.Check out our infographic A sip of… on the website page for this episode, summarising 5 key points on this topic. It’s made for sharing!