5.10 Supporting Carers

Episode 5.10 – Supporting Carers

For a PDF of this sip of MDTea click here

For a PDF of the show notes click here

Presented by: Dr Iain Wilkinson and Dr Jo Preston

Guests: Chris O’Connor – Admiral Nurse

Jackie Lelkes – Social Worker

CPD log

Click here to log your CPD online and receive a copy by email.

Social Media This Week

1)

This is possibly the best and most useful article I have ever read in a journal.

Credit to Jason Walker – a consultant anaesthetist in Bangor. Do you know him @mmbangor ? If so, thank him profusely!!! pic.twitter.com/kEvIhnUzRT

— Rowan Wallace (@rowan_wallace) March 24, 2018

2) Can community care workers deliver a falls prevention exercise program? A feasibility study.

Conclusion

Community care workers who have completed appropriate training are able to deliver a falls prevention exercise program to their clients as part of their current services. Further research is required to determine whether the program reduces the rate of falls for community care clients and whether integration of a falls prevention program into an existing service is cost-effective.

Learning Outcomes

Knowledge:

- To explore the role of carers

- To know that caring can be a strain for the caregiver and on the relationship with the person needing care

Skills:

- To understand the impact of the caring role

- To develop an awareness of the entitlement to a carers assessment

Attitudes:

- To understand the impact of the caring role on carers

- To recognise the role of male carers

Show notes

Definitions:

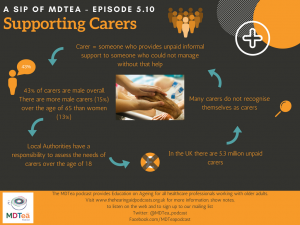

- There is no one single definition of a carer, but a widely accepted definition is that a carer can be defined as someone, adult or child, who provides unpaid informal support to family or friends who could not manage without this help.

- This would include caring for a friend or family member who due to illness, disability, a mental health problem or an addiction cannot cope without their support.

- A role that is often underpinned with love and affection as well as a sense of duty. In addition it is important to remember that some carers can derive personal satisfaction in delivering this role.

- Oyebode (2003) points out that that it is important to remember that the caring role is not a static process the carer having to adjust their role as the needs of the person receiving care alters as their condition changes,

- “It is not surprising, therefore, that being a carer often raises difficult personal issues about duty and responsibility, adequacy and guilt”, all of which impact on their well-being.

Assessment of carers’ psychological needs 2003

Iain to talk about Tronto’s framework for understanding the concept of care identifying four aspects to care: Caring about, taking care of, care-giving and care receiving.

Tronto, J., 1993. Moral boundaries: a political argument for an ethic of care. New York: Routledge

- The majority of carers’ provide between 1 -9 hours care a week undertaking tasks such as shopping and cleaning.

- However, 2.9% of the female population and 2% of the male population provided intensive care of 50 plus hours a week.

In reality many people do not recognise themselves as a carer but identify as a husband, a wife, a daughter, a son, a friend, a view, which has the potential to impact on the figures.

We all can make a basic assessment of carers needs and refer onto appropriate, more qualified people.

http://www.bmj.com/content/343/bmj.d5202

According to the Office of National Statistics – census in 2011:

- There are around 5.3 million unpaid carers

- Provision of unpaid care has increased since 2001 (by around 600,000)

- Projections suggest the demand for such care will more than double over the next 30 years’ by 2037 the estimate being 9 million carer, with the number of female carers being notably higher.

- In 2011 57.7% of carers were female and 42.3% were male.

- The highest share of the unpaid care burden falling on men and women aged 50-64.

- In addition the census indicated that when women reach 50 they are likely to spend 5.9 years of their remaining life as unpaid carers.

- In contrast, men at 50 are likely to spend 4.9 years of their remaining life as an unpaid carer,.

The Office of National Statistics. Full story: The gender gap in unpaid care

provision: is there an impact on health and economic position?

- However by the age of 65, these figures reverse, with women likely to spend 2.6 of their remaining years as unpaid carers, and men 2.7 years.

- In addition there are more male carers (15%) than women (13%).

- Older people provide almost half the co-resident care for older care-recipients, the care taking place predominately within the context of spouse-type relationship, which leads to greater provision of personal care tasks and increased hours of care giving.

- In addition there is a significant increase in the amount of care the carer is providing to a person with dementia, which increases the risk of stress related illness for the carer.

The rise in unpaid carers can be attributed to an ageing population brought about by improved life expectancy for people with long term conditions or complex disabilities, meaning more high level care need to be provided for a longer period of time.

The provision of unpaid care is an important social policy issue because without the input of unpaid care there would be a huge impact on the supply of care, which would be in a greater crisis that it currently is,

- Only last year (2017) Analysis produced by the Office for Budget Responsibility, which accompanied the Autumn Budget showed that English councils withdrew £1.4bn from emergency reserves, with experts say is ‘unsustainable’ in relation to providing social care.

- According to the Kings Fund Local authorities face a huge funding shortfall that is set to reach £2.5bn by 2020.

In addition to the shortfall in funding it is estimated that unpaid carers save the government £119bn a year (Buckner, 2011). The willingness of informal carer to continue in this role therefore places them at the centre of future social care planning.

Across the EU, care policies have tended to develop in isolation from policies for employment/equal opportunities. In the few countries (such as Finland and Denmark) that are beginning to take a more strategic approach to older people’s issues, the issue of support for employed carers is beginning to be addressed, partly because of the strong similarities to the business case for older workers – indeed, many working carers of older people are also older workers.

Impact of the caring role:

Government research on carers shows that people who provide a substantial amount of care tend to have lower incomes, poorer health, and are less likely to be in work than their counterparts (DH 2008)

The organization Carers UK states that; “The difficulties experienced by carers can be highlighted by the following three statistics:

- Carers lose on average £11,050pa by taking on significant caring responsibilities. Quince(2011) identifying that many carers face financial concerns and have to use their private savings to meet household bills and the additional costs incurred due to the need of the person they care fore such as heating, laundry and specialist equipment i.e. a stair lift.

- Over half of all carers have a caring-related health condition, with 625,000 people suffering mental and physical ill health as a direct consequence of the stress and physical demands of caring. The Prepared to Care Report (Carers Week, 2013) found that six out of ten carers have experienced injury or their physical health has suffered because of their caring role.

- Carers represent one of the most socially excluded groups of people.”

(Carers UK 2009)

As many carers struggle with the demands of their role, the first thing to get lost is often a carer’s sense of self, of their own wellbeing. They can experience an enhanced level of anxiety and stress, particularly if they are subject to:

- Increased physical or verbal abuse,

- Being woken during the night; which

- Leads to a lack of sleep.

Issues, which may be higher for those people caring for people with dementia, where there is also an additional emotional demand (Cheffings, 2003)

Cheffings J. 2003. Report of the Princess Royal Trust for Carers. Princess Royal

Trust for Carers, London

Asking the question “Overall how burdened do you feel?” is a useful, quick way to assess carer distress.

http://www.bmj.com/content/343/bmj.d

There may be particular stresses associated with caring for someone with mental health needs, for example:

- Mental illness and emotional problems can alter behaviour in ways that relatives find distressing. For instance: an older person with dementia may not recognise family members; the long-term effects of some medication may lead to a loss of sexual inhibitions. The older person may no longer seem to be the same person – no longer the person the relative had known and loved.

- Mental illness and emotional problems can alter relationships. The hopelessness, despair and apathy of a severely depressed person can be very hard to live with, for example. And forgetting that you are married or have a daughter can make it hard to maintain meaningful family relationships.

- The stigma of mental illness remains powerful in our society. It is not unusual for carers to feel ashamed or embarrassed that their relative has mental health problems, or guilty that this is the way they feel.

- The carer’s own social life may be affected. Social occasions may become difficult or embarrassing, and so social gatherings or going out may be avoided.

- Changes in behaviour may mean that the older person cannot be left on their own safely, so that even a quick dash to the shops becomes fraught with anxiety.

- Day-to-day frustrations, such as endless repetition, being continually followed around, or being unable to encourage the older person to complete the simplest task, may have a serious cumulative effect on the carer’s ability to cope.

Assessing the mental health needs of older people. SCIE

Working with carers

It is important not to make any assumptions, regarding a carer’s capacity or willingness to either start to take responsibility for, or to continue to care for a person.

- Carers should be an active participant in any assessment and decision making, as they have a vast understanding of the needs of the person they care for

- It is important to acknowledge that the carer may have different views from that of the cared for person and that the views of all parties should be considered and balanced where possible.

- Having a break from caring is vital to the wellbeing of carers, and has been recognised as such by national policy (Department of Health, 1999).

- However when the carer is caring for a person with dementia this can be particularly difficult due to the problems of communication and orientation to the new environment.

- It is important to respect and recognise that carers will have their own support needs, rights and aspirations, which may be different from that of the cared for person and that for the carer to engage in activities important to them this may at times involve an assessment of risk and the need to respond appropriately and manage this proportionately.

- It is also important to recognise that the caring role will come to an end and to consider that the carer will experience loss and grief, for which support may be required.

Discover Skills for Carers – a europe wide study looking at digital technology to help careres

- Online carers in the UK report internet saves time (70%), saves money (40%) and reduces feeling of isolation (42%)

- 90% of carers think computers could make their life easier and 27% think they enable more time for each other

Male carers

- The caring role has historically been identified as a role undertaken by females but the number of male carers, particularly amongst older carers is high, with more that four in ten (42%) of the UK’s unpaid carers being male, dispelling the myth that most carers are female.

- Recent studies of male carers have supported the emergent perspective that they are capable, nurturing and innovative in the role; indeed, their representation has changed from being ‘ineffective or inconsequential’ to ‘capable and competent’ carers

Russell 2001 cited in Riberio and Paul, 2008)

The Carers Trust and the Men’s Health Forum report ‘Husband, Partner, Dad, Son, Carer?’ looks into the experiences and needs of male carers to raise awareness of the needs of this group of carers.

The report found the following:

- Over one in four male carers in employment would not acknowledge themselves as a carer,

- which potentially impacts on the support they obtain at work – it is important to remember that people work longer and the retirement age is being extended.

- In 2016 there were 10.4% (1.19 million) aged 65 and over in employment in the period for May to July 2016 of whom 742,000 where men (Office of National Statistics)

- 53% of male carers surveyed felt that their needs differed from those of female carers,

- for example many felt that men find it harder to ask for help and support and as the main earner they find it challenging to balance work and caring commitments

- 26.3% of men surveyed cared for more than 60 hours per week and worked

- Four in ten male carers said that they never had a break from their caring role.

- A concern as Singleton et al (2002) identify that fewer carers experience mental health problems if they have taken a break since beginning their caring role.

- 56% of male carers aged 18-64 stated that their caring role had had a negative impact on their mental health identify issues such as stress, anxiety, fatigue and fear

- 55% said that their health was “fair or poor”. A result matched by the research, which widely recognises the impact on health e.g. higher levels of back problems and sleep disturbance being common problems.

- Eight out of ten male carers who are not working due to their caring commitments expressed the view that they felt isolated and missed the opportunity to spend time with friends and family members.

- Singleton et al (2002) research highlighting that 35% of carers without good social support experienced ill health compared with 15% of those with good support

- Just fewer than 50% of respondents had not had a carer’s assessment. Although Male carers aged 18–64 are even less likely to have had a carer’s assessment than those over 65.

Husband, Partner, Dad, Son, Carer?

For those male cares who continue to work Carers UK (2014) found that:

“There is important evidence that working age men who do care, ………can face greater financial and workforce disadvantage. Whilst a greater proportion of working age men combine full-time work and caring, greater incidence of ‘partner caring’ and less part-time working mean that men are more likely to give up work entirely or retire early to care and are very significantly more likely to be in a household where no one is in paid work.”

- Milligan and Morbey (2013) believe that particular important in the older male carer narratives were expressions of loss in relation to loss of futures, relationships, plans, and friends. The loss experienced in many areas of their lives i.e.no longer being able to enjoy joint pleasurable interests, sexual intimacy, ‘normal’ conversations, family worries or traumas with their partner.

- Milligan and Morbey (2013) research also identified how the caring role for older male carers impacted on their gender identity in two ways; personal and relational. Identify shaped by societal perceptions and interpretations of their role and the tasks they undertake. “Some male carers described perceptions of others, be they relatives, friends, acquaintances or health professionals, as conferring a low status and value upon caring as a valid and valued role “ (p 13)

- Research also indicates that older male carers are less likely to ask for help, tending to reach crisis point before they will make a request for support.

- However it is not all negative Ribeiro and Paul (2003) identified that older male cares felt that “fulfilling one’s duty and commitments” was the most frequent reasons for having positive feelings about their caring role. Giving them both a role and an ability to demonstrate their commitment to their spouse (Milne and Hatzidimitriadou’s (2003: 402).

- McGarry and Arthur (2001) research establishing that, for older carers, the quality of the relationship before the onset of care-giving is a key prior condition for a husband to be positive about caring for his wife.

- Ribeiro and Paul (2003:170 -171) research supporting the view that ‘just being there’ keeping their wives company, was the most frequent reason given for finding satisfaction in the role, this remained true even when the cared for was passive and unable to communicate (e.g dementia).

- Wanting to stay together for as long as possible, delaying the need for residential care and separation, with the associated feeling of ‘loneliness and purposelessness’. Linked to this for a small number of men in the research (19%) was the expression of providing care so as to not feel guilty.

Carers’ assessment:

Much of the research shows that cares are reluctant to access support both formal and formal. There may be a number of reasons for this including:

- A lack of information,

- Reluctance to use services because of a sense of duty; and

- Restrictions in service use due to cost or lack of availability

The Care Act, 2014, gives Local authorities (LA’s) a responsibility to assess the needs of carer’s over the age of 18, regardless of the type or level of care that the person is providing, or their financial affairs. The entitlement to this assessment IS NOT dependent on the cared for having had a needs assessment, or meeting the eligibility criteria for care in their own right.

To receive support the carer must be assessed by the LA as having ‘eligible needs’, the Care Act outlining that the persons caring role as likely to have a significant impact on the person’s wellbeing because of their caring role.

There are three questions the local council will have to consider in making their decision:

- Are the person’s needs the result of them providing necessary care?

- Does the caring role have an effect on them?

- Is there, or is there likely to be, a significant impact on their wellbeing?

The Care Act (2014) states that all assessments must be carried out in a manner which:

- Is appropriate and proportionate to the persons needs and circumstances

- Ensures that they are able to participate effectively in the assessment

- Has regard to their choices, wishes and the outcomes they want to achieve

- Takes account of the level and severity of their needs

When undertaking the assessment it is important:

- To empower the carer to remain in or regain control of their life. Carers often have the potential to find their own solutions, with support to set goals

- To consider what the carer and their informal network are already doing for themselves or have the potential to do with a little help.

- Services or interventions should build upon the informal network of support from friends and the local community.

- That Carers are well informed and connected to support in their local community as they are then better able and willing to continue caring for longer.

- To respect the carer’s wishes to do things with or without the person they care for.

The assessment should cover the following areas:

- The persons caring role and how it affects their life and wellbeing

- Their health – physical, mental and emotional issues

- Their feelings and choices about caring

- Work, study, training, leisure

- Relationships, social activities and your goals

- Housing

- Planning for emergencies (such as a Carer Emergency Scheme).

If the carer has ‘substantial difficulty’ in communicating their wishes, or understanding, retaining and assessing information during the assessment and there is no other appropriate person who is able and willing to help them then an independent advocate should be appointed by the LA.

References:

Carers UK: Facts and Figures. [on-line] Available at: https://www.carersuk.org/news-and-campaigns/press-releases/facts-and-figures

Carers UK. 2016. Assessment your guide to getting care and support. [on-line] available at: http://www.carersuk.org/files/helpandadvice/4765/factsheet-e1029–assessments-your-guide-to-getting-care-and-support.pdf

Cheffings J. 2003. Report of the Princess Royal Trust for Carers. Princess Royal Trust for Carers, London

Dury, R. 2014. Older Carers in the UK: Who Cares? British Journal of Community Nursing.

The Office of National Statistics. Full story: The gender gap in unpaid care provision: is there an impact on health and economic position? [online]. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandwellbeing/articles/fullstorythegendergapinunpaidcareprovisionisthereanimpactonhealthandeconomicposition/2013-05-16

Carers Trust and the Men’s Health Forum. 2014. Husband, Partner, Dad, Son, Carer?’ [0nline] Available at: https://www.menshealthforum.org.uk/sites/default/files/pdf/male_carers_research_report.pdf

McGarry, J. and Arthur, A. 2001. Informal care in late life: a qualitative study of the experiences of older carers. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 33, 2, 182–90.

Milligan, C and Morbey, H (2013), Older Men Who Care: Understanding their Support and Support Needs [on-line] Available at: http://eprints.lancs.ac.uk/68443/1/Older_men_who_care_report_2013Final.pdf

Oyebode, J. (2003). Assessment of carers’ psychological needs. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 9(1), 45-53.

RIBEIRO, O., & PAÚL, C. (2008). Older male carers and the positive aspects of care. Ageing and Society, 28(2),

Singleton, N, Maung, NA, Cowie, A, Sparks, J, Bumpstead, R, Meltzer, H (2002), Mental Health of Carers (London: Office of National Statistics, The Stationery Office).

Skills for Care. 2012. The Common Core Principles of working with carer [0n-line]. Available at: http://www.skillsforcare.org.uk/Documents/Topics/Supporting-carers/Common-core-principles-for-working-with-carers.pdf

Curriculum Mapping:

| Curriculum | Area | |

| NHS Knowledge Skills Framework | Suitable to support staff at the following levels:

| |

| Foundation curriculum | Section

10 | Title

Recognises, assesses and manages patients with long term conditions |

| Core Medical Training | The patient as central focus of care

Managing Long-Term Conditions and Promoting Patient Self-care Memory Loss (Progressive) | |

| Dementia Core Skills and Education | Section 9 | |

| Geriatric Medicine Higher Specialist Training | 3.2.6 Planning Transfers of Care and Ongoing Care Outside Hospital

6. The Patient as Central Focus of Care 11. Managing Long-Term Conditions and Promoting Patient Self-care 29. Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Disease and Disability 33. Dementia | |

| GPVTS program | Section 2.03 The GP in the Wider Professional Environment

Section 3.05 – Managing older adults

| |

| ANP (Draws from KSF) | Section 16: Demonstrates knowledge of local voluntary services/community groups or organisations that can support the patient and/or their family/carers.

20. The Patient as Central Focus of Care 29. Communication |